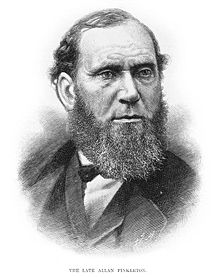

Allan Pinkerton

Allan Pinkerton | |

|---|---|

c.1861 | |

| Born | August 21, 1819 Glasgow, Scotland |

| Died | July 1, 1884 (aged 64) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Resting place | Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Cooper, abolitionist, detective, spy |

| Spouse |

Joan Carfrae (m. 1842) |

| Children | 3 |

Allan Pinkerton (August 21, 1819[1] – July 1, 1884) was a Scottish-American cooper, abolitionist, detective, and spy, best known for creating the Pinkerton National Detective Agency in the United States and his claim to have foiled a plot in 1861 to assassinate president-elect Abraham Lincoln. During the Civil War, he provided the Union Army – specifically General George B. McClellan of the Army of the Potomac – with military intelligence, including extremely inaccurate enemy troop strength numbers.[2] After the war, his agents played a significant role as strikebreakers – in particular during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 – a role that Pinkerton men would continue to play after the death of their founder.

Early life

[edit]Allan Pinkerton was born in the Gorbals, a working-class area of Glasgow, on August 21, 1819,[3] the second surviving son[1] of William Pinkerton, a retired policeman, and Isobel McQueen;[4] he was baptized on August 25, 1819, which many sources incorrectly give as his birthdate.[1] He left school at the age of 10 after his father's death. Pinkerton read voraciously and was largely self-educated.[5] A cooper by trade,[6] he was active in the Scottish Chartist movement as a young man.[7] He was not raised in a religious upbringing, and was a lifelong atheist.[8]

Pinkerton emigrated to the United States in 1842. In 1843, he heard of Dundee Township, Illinois, fifty miles northwest of Chicago on the Fox River.[9] He built a cabin and started a cooperage, sending for his wife in Chicago when their cabin was complete.[9] As early as 1844, Pinkerton worked for the Chicago abolitionist leaders, and his Dundee home was a stop on the Underground Railroad.[10]

Detective

[edit]Pinkerton first became interested in criminal detective work while wandering through the wooded groves around Dundee, looking for trees to make barrel staves, when he came across a band of counterfeiters,[11] who may have been affiliated with the notorious Banditti of the Prairie. After observing their movements for some time he informed the local sheriff, who arrested them. This later led to Pinkerton being appointed, in 1849, as the first police detective in Chicago, Cook County, Illinois. In 1850, he partnered with Chicago attorney Edward Rucker in forming the North-Western Police Agency, which later became Pinkerton & Co, and finally Pinkerton National Detective Agency, still in existence today as Pinkerton Consulting and Investigations, a subsidiary of Securitas AB. Pinkerton's business insignia was a wide open eye with the caption "We never sleep." As the US expanded in territory, rail transport increased. Pinkerton's agency solved a series of train robberies during the 1850s, first bringing Pinkerton into contact with George B. McClellan, then Chief Engineer and Vice President of the Illinois Central Railroad, and Abraham Lincoln, a lawyer who sometimes represented the company.

In 1859, he attended the secret meetings held by John Brown and Frederick Douglass in Chicago along with abolitionists John Jones and Henry O. Wagoner. At those meetings, Jones, Wagoner, and Pinkerton helped purchase clothes and supplies for Brown. Jones' wife, Mary, guessed that the supplies included the suit Brown was hanged in after the failure of John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in November 1859.[12]

American Civil War

[edit]

When the Civil War began, Pinkerton served as head of the Union Intelligence Service during the first two years, heading off an alleged assassination plot in Baltimore, Maryland while guarding Abraham Lincoln on his way to Washington, D.C., as well as providing estimates of Confederate troop numbers to General George B. McClellan when he commanded the Army of the Potomac. His agents often worked undercover as Confederate soldiers and sympathizers to gather military intelligence. Pinkerton himself served on several undercover missions as a Confederate soldier using the alias Major E.J. Allen. He worked across the Deep South in the summer of 1861, focusing on fortifications and Confederate plans. He was found out in Memphis and barely escaped with his life. This counterintelligence work done by Pinkerton and his agents is comparable to the work done by today's U.S. Army Counterintelligence Special Agents in which Pinkerton's agency is considered an early predecessor.[13] He was succeeded as Intelligence Service chief by Lafayette Baker; the Intelligence Service was the predecessor of the U.S. Secret Service. His work led to the establishment of the Federal secret service.[14]

Military historians have been strongly critical of the intelligence Pinkerton provided for the Union Army, which for the most part was undigested raw data.[2] In the view of T. Harry Williams, Pinkerton's work was "the poorest intelligence service any general ever had."[15] Pinkerton's estimates of Rebel troop numbers, derived from his credulous interrogations of Confederate prisoners, deserters, refugees, escaped slaves ("contrabands"), and civilians unused to counting large bodies of men, badly exaggerated the size of those formations, sometimes almost doubling their actual strength. Pinkerton's numbers caused McClellan to consistently believe that he was drastically outnumbered by the Confederate forces he faced. McClellan's action in the face of what he believed were overwhelming odds were unduly cautious, causing him to avoid offensive actions almost completely in favor of siege warfare and taking a defensive posture. This led to his retreat in the Peninsula Campaign, his failure to crush Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at the Battle of Antietam, and his unnecessary delay in carrying out his orders to pursue Lee's army as they retreated from their invasion of Maryland back into Virginia. These actions were all based on McClellan's firm trust of Pinkerton's reports, although the problem was compounded by the intelligence-gathering ineptitude of Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton, McClellan's head cavalryman and his alternate source of enemy troop information when Pinkerton did not have agents in place.[16][17][a]

On the other hand, Edwin C. Fishel in The Secret War for the Union and James Mackay in Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye argue that the troop strength figures which Pinkerton passed on to McClellan were relatively accurate, and that McClellan himself held primary responsibility for inflating those numbers to wildly unrealistic levels.[18][19]

After the war

[edit]Following Pinkerton's services for the Union Army, he continued his pursuit of train robbers, including the Reno Gang. He was hired by the railroad express companies to track outlaw Jesse James, but after Pinkerton failed to capture him, the railroad withdrew their financial support and Pinkerton continued to track James at his own expense. After James allegedly captured and killed one of Pinkerton's undercover agents (who was working undercover at the farm neighboring the James family's farmstead), he abandoned the chase. Some consider this failure Pinkerton's biggest defeat.[20] In 1872, the Spanish Government hired Pinkerton to help suppress a revolution in Cuba which intended to end slavery and give citizens the right to vote.[21] If Pinkerton knew this, then it directly contradicts statements in his 1883 book The Spy of the Rebellion, where he professes to be an ardent abolitionist and hater of slavery. The Spanish government abolished slavery in 1880 and a Royal Decree abolished the last vestiges of it in 1886.

Personal life

[edit]Pinkerton married Joan Carfrae (1822–1887), a singer from Duddingston, in Glasgow on March 13, 1842.[22] They remained married until his death. They had six children: Isabella, William, Joan, Robert, Mary, and Joan.

Death

[edit]Pinkerton died in Chicago on July 1, 1884. It is usually said that Pinkerton slipped on the pavement and bit his tongue, resulting in gangrene.[23] Contemporary reports give conflicting causes, such as that he succumbed to a stroke – he had a year earlier – or to malaria, which he had contracted during a trip to the Southern United States.[24] At the time of his death, he was working on a system to centralize all criminal identification records; such a database is now maintained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Pinkerton is buried between his wife and Kate Warne in the family plot in Graceland Cemetery, Chicago.[25] He is a member of the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame.[26]

Legacy

[edit]After his death, the agency continued to operate and soon became a major force against the labor movement developing in the US and Canada. This effort changed the image of the Pinkertons for years. They were involved in numerous activities against labor during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including:

- The Homestead Strike (1892), the direct impetus for the federal Anti-Pinkerton Act of 1893, prohibiting the federal government from hiring its detectives

- The Pullman Strike (1894)

- The Wild Bunch Gang (1896)

- The Ludlow Massacre (1914)

- The La Follette Committee (1933–1937)

Despite his agency's later reputation for anti-labor activities, Pinkerton himself was heavily involved in pro-labor politics as a young man.[27] Though Pinkerton considered himself pro-labor, he opposed strikes and distrusted labor unions.[28]

Allan Pinkerton was so famous that for decades after his death, his surname was a slang term for a private eye, whether they were agents of the Pinkerton Agency or not. The "Mr. Pinkerton" novels, by American mystery writer Zenith Jones Brown (under the pseudonym David Frome), were about Welsh-born amateur detective Evan Pinkerton and may have been inspired by the slang term.

Writings

[edit]Pinkerton produced numerous popular detective books, ostensibly based on his own exploits and those of his agents. Some were published after his death, and they are considered to have been more motivated by a desire to promote his detective agency than a literary endeavour. Most historians believe that Allan Pinkerton hired ghostwriters, but the books nonetheless bear his name and no doubt reflect his views.[29]

- —; William Henry Herndon; Jesse William Weik (1866). Allan Pinkerton's Unpublished Story of the First Attempt on the Life Of Abraham Lincoln. Phillips Publishing Co.

- —; William Henry Herndon; Jesse William Weik (1868). History and Evidence of the Passage of Abraham Lincoln from Harrisburg, Pa., to Washington, D.C., on the 22d and 23d of February, 1861. Phillips Publishing Co.

- — (1874). The Expressman and the Detective. Chicago: W. B. Keen, Cooke & Co.

- — (1875). Claude Melnotte As A Detective, And Other Stories. Chicago: W. B. Keen, Cooke & Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1875). The Somnambulist and the Detective, The Murderer and the Fortune Teller. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1876). The Spiritualists and the Detectives. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. ISBN 978-1-02-234724-3. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1877). The Molly Maguires and the Detectives, 1905 ed. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1878). Strikers, Communists, Tramps and Detectives. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1878). Criminal Reminiscences and Detective Sketches. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1879). Mississippi Outlaws and the Detectives, Don Pedro and the Detectives, Poisoner and the Detectives. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1879). The Gypsies and the Detectives. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1880). Bucholz and the Detectives. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009. Also available via Project Gutenberg

- — (1881). The Rail-Road Forger and the Detectives. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1883). The Spy of the Rebellion: Being a True History of the Spy System of the United States Army During the Late Rebellion. Hartford, Conn.: M. A. Winter & Hatch. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1884). A Double Life and the Detectives. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1886). Professional Thieves and the Detective: Containing Numerous Detective Sketches Collected From Private Records. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1886). A Life for a Life: Or, The Detective's Triumph. Laird & Lee.

- — (1892). Cornered at Last: A Detective Story.

- — (1900). Thirty Years a Detective: A Thorough and Comprehensive Expose of Criminal Practices of all Grades and Classes. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- — (1900). The Model Town and the Detectives, Byron as a Detective. New York: G. W. Dillingham Co. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

In popular culture

[edit]- In the 1951 feature film The Tall Target, a historical drama loosely based on the Baltimore Plot, Allan Pinkerton is portrayed by Scottish actor Robert Malcolm. The M-G-M production stars Dick Powell and was directed by Anthony Mann.

- In the 1956 episode "The Pinkertons" of the ABC/Desilu western television series, The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, set in Wichita, Kansas, Douglas Evans portrays Allan Pinkerton, who is seeking to recover $40,000 in stolen money but interferes with the attempt of Marshal Wyatt Earp (Hugh O'Brian) to catch the entire gang of Crummy Newton (Richard Alexander).

- In the 1969 Spaghetti Western The Price of Power, Pinkerton appears as an associate of President James A. Garfield who takes part in his (highly fictionalized) assassination. He is portrayed by Spanish actor Fernando Rey.

- Pinkerton is portrayed in an episode of The Life and Times of Grizzly Adams (1974) by Don Galloway.

- In 1990, Turner Network Television aired the 1990 speculative historical drama The Rose and the Jackal, with Christopher Reeve as Pinkerton, recounting his (completely fictional) romance with the Confederate spy Rose O'Neal Greenhow.

- In 1994, "Pinkertonova detektivní agentura" ('Pinkerton's Detective Agency") [30] an episode of the Czech TV series Dobrodružství kriminalistiky ("The Adventure of Criminology") was aired.

- Pinkerton is portrayed in the 1994 American biographical western film Frank and Jesse by William Atherton

- Pinkerton is a major character portrayed by Timothy Dalton in the 2001 film American Outlaws.

- Pinkerton's role in foiling the assassination plot against Abraham Lincoln was dramatized in the 2013 film Saving Lincoln, which tells President Lincoln's story through the eyes of Ward Hill Lamon, a former law partner of Lincoln who served as his primary bodyguard during the Civil War. Pinkerton is played by Marcus J. Freed.

- Charlie Day portrayed Pinkerton in "Baltimore", a Season 2 episode of the docudrama TV series Drunk History, first broadcast on July 22, 2014.

- Pinkerton is a recurring character played by Angus Macfadyen in the 2014 TV series The Pinkertons.

- Pinkerton is an important character in Steven Price's 2016 novel By Gaslight.

- The Pinkerton Detective Agency plays a large role in the plot of the 2018 western video game Red Dead Redemption 2.

- "The Pinkerton Agency" is a podcast episode of the Dollop in 2024.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Informational notes

- ^ McClellan was so committed to believing Pinkerton's numbers, that even years later, at a time when those numbers were well known to have been widely inaccurate, he used them in writing his memoirs. McClellan had employed Pinkerton as a detective when he was an executive of the Illinois Central railroad, and his service to McClellan during the war was as a civilian employee working from the provost marshall's office, not as a member of the Union Army. To some extent, McClellan himself was responsible for the exaggerated numbers, as he had instructed Pinkerton to overestimate in order to account for troops not yet found. Pinkerton's sycophancy undoubtedly also contributed, as he provided for his boss the kind of numbers that it was obvious McClellan expected to receive. See Murfin (2004) [1965], Sears (1988) and Sears (2017), p. 84

Citations

- ^ a b c Mackay (1997), p. 20; August 25 was the date of his baptism, which many sources incorrectly give as his birthdate.

- ^ a b Sears (2017), p. 104

- ^ "1819 Pinkerton, Allan (Old Parish Registers Births 644/ 2 Gorbals) Page 107 of 113". Scotland's People. National Records of Scotland and the Court of the Lord Lyon.

- ^ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (July 20, 1998). "Allan Pinkerton". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ Hunt, Russell A. (2009). "Allan Pinkerton: America's first private eye (1819–1884)". The Forensic Examiner. 18 (4): 42–46. ProQuest 347552047. Retrieved November 28, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Seiple (2015), pp. 10–11

- ^ Seiple (2015), pp. 11–13

- ^ Davenport-Hines, Richard (2004). "Pinkerton, Allan (1819–1884)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49497. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

Although christened by a Baptist minister in the Gorbals (August 25, 1819), he had a churchless upbringing and was a lifelong atheist

(Subscription or UK public library membership required.) - ^ a b Horan (1969), p. 13

- ^ Horan (1969), p. 19

- ^ Seiple (2015), pp. 16–17

- ^ Junger, Richard (2009) "Thinking Men and Women who Desire to Improve our Condition: Henry O. Wagoner, Civil Rights, and Black Economic Opportunity in Frontier Chicago and Denver, 1846–1887" in Alexander, William H.; Newby-Alexander, Cassandra L.; and Ford, Charles H. eds Voices from within the Veil: African Americans and the Experience of Democracy. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, p. 154

- ^ Stockham, Braden (2017). "Chapter 2: Literature Review: Historical Background". The Expanded Application of Forensic Science and Law Enforcement Methodologies in Army Counterintelligence (Thesis). Fort Belvoir, Virginia: Defense Technical Information Center. p. 6.

- ^ Hart, James D. and Leininger, Philip W., eds. (2004). "Pinkerton, Allan". The Oxford Companion to American Literature. Oxford. ISBN 978-0195065480.

- ^ Williams, T. Harry (2000) [1952] Lincoln and His Generals. New York: Gramercy Books. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-517-16237-8

- ^ Sears, Stephen (1988) George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon New York: Da Capo Press. pp. 107–110, 274. ISBN 978-03068091-32

- ^ Murfin, James V. (2004) [1965] The Gleam of Bayonets Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 40, 45, 50, 54–55, 125. ISBN 978-0-8071-3020-9

- ^ Fishel, Edwin C. (1996) The Secret War for the Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War. Boston: Mariner Books. pp. 103–129. ISBN 0-395-90136-7

- ^ Mackay (1997), pp. 8–9

- ^ Stiles, T. J. (2003). Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War. New York: Vintage. ISBN 9780375705588.

- ^ Norwood, Stephen H. (December 1998) "Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye by James Mackay" (review) Journal of American History v. 85, n. 3, pp. 1106–1107

- ^ ScotlandsPeople OPR Banns & Marriages Record 644/001 0420 0539

- ^ Bumgarner, Jeff (2008). Icons of Crime Fighting: Relentless Pursuers of Justice. ABC-CLIO. p. 49. ISBN 9781567206739.

- ^ Lanis, Edward Stanley (1949) Allan Pinkerton and the Private Detective Institution (M.S. Thesis). p. 170, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

- ^ Dickinson, Rachel (2017). The Notorious Reno Gang: The Wild Story of the West's First Brotherhood of Thieves, Assassins, and Train Robbers. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 207. ISBN 9781493026401.

- ^ Swank, Mark A. and Swank, Dreama J. (2013). Maryland in the Civil War. Arcadia Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 9781467120418.

- ^ "Allan J. Pinkerton". Thrillingdetective.com. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ Pinkerton, Allan (1878). Strikers, Communists, Tramps and Detectives. G. W. Carleton & Company. pp. 14–7.

- ^ Mackay (1997), pp. 208–209

- ^ Pinkertonova detektivní agentura (Television production) (in Czech). Retrieved November 28, 2021.

Bibliography

- Horan, James D. (1969) [1967]. The Pinkertons: The Detective Dynasty That Made History. New York: Crown Publishers.

- Mackay, James (1997) Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0471194156

- Sears, Stephen W. (2017) Lincoln's Lieutenants Boston: Mariner Books. ISBN 978-1-328-91579-5

- Seiple, Samantha (2015). Lincoln's Spymaster: Allan Pinkerton, America's First Private Eye. New York: Scholastic Press. ISBN 978-0-545-70897-5.

Further reading

- Josephson, Judith Pinkerton (1996) Allan Pinkerton: The Original Private Eye Minneapolis, Minnesota: Lerner. ISBN 9780822549239

External links

[edit]- Works by Allan Pinkerton at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Allan Pinkerton at the Internet Archive

- Works by Allan Pinkerton at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- University of Chicago's library database

- University of Toronto's library database

- Detailed profile of Pinkerton

- Allan Pinkerton, in The Scotsman's Great Scots series

- A Brief History of the Pinkertons Archived January 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- 1819 births

- 1884 deaths

- Pinkerton (detective agency)

- Baltimore Plot

- American police detectives

- Private investigators

- American atheists

- American Civil War spies

- Chartists

- People from Gorbals

- Writers from Chicago

- Scottish emigrants to the United States

- Burials at Graceland Cemetery (Chicago)

- Accidental deaths in Illinois

- Abraham Lincoln

- Underground Railroad people

- People of the American Old West

- Scottish atheists

- Anti-crime activists

- Union army civilians

- Scottish abolitionists

- Scottish spies

- Scottish company founders

- 19th-century Scottish businesspeople