San Joaquin Valley

| San Joaquin Valley | |

|---|---|

| Valle de San Joaquín (Spanish) | |

San Joaquin Valley | |

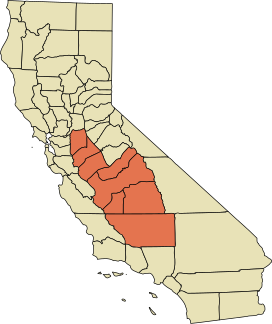

A map of the counties encompassing the San Joaquin Valley ecoregion | |

| Geography | |

| Location | California, United States |

| Population centers | Stockton, Tulare, Porterville, Modesto, Turlock, Merced, Fresno, Visalia, Bakersfield, Clovis, Hanford, Madera, Tracy, Lodi, Galt, Manteca and Ceres. |

| Borders on | Sierra Nevada (east), Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta (north), Coast Range, San Francisco Bay (west), Tehachapi Mountains (south) |

| Coordinates | 36°37′44″N 120°11′06″W / 36.62889°N 120.18500°W |

| Traversed by | Interstate 5, State Route 99 |

| Rivers | San Joaquin River |

The San Joaquin Valley (/ˌsæn hwɑːˈkiːn/ SAN whah-KEEN; Spanish: Valle de San Joaquín) is the southern half of California's Central Valley. Famed as a major breadbasket,[1] the San Joaquin Valley is an important source of food, producing a significant part of California's agricultural output.

San Joaquin Valley draws from eight counties of Northern and one of Southern California, including all of San Joaquin and Kings counties, most of Stanislaus, Merced, and Fresno counties, and parts of Madera and Tulare counties, along with a majority of Kern County in Southern California.[2] Although the valley is predominantly rural, it has three densely populated urban centers: Stockton/Modesto, Fresno/Visalia, and Bakersfield.[3]

Geography

[edit]

The San Joaquin Valley is the southern half of California's Central Valley.[4] It extends from the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta in the north to the Tehachapi Mountains in the south, and from the California coastal ranges (Diablo and Temblor) in the west to the Sierra Nevada in the east.[5][6]

The valley contains two large river systems, divided north and south. The northern portion of San Joaquin Valley is called the San Joaquin Basin: the watershed of the San Joaquin River and its tributaries including parts of the Kings River, all of which drain northwest into the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and eventually out to the Pacific Ocean. The somewhat larger southern portion is the Tulare Basin, an endorheic basin centered on Tulare Lake.[4] Historically, Tulare Lake was fed by the Tule River, the Kings River, the Kaweah River, the White River and the Kern River, but much of this water has been diverted for agricultural uses and the watershed is mostly dry in its lower reaches.

Geological history

[edit]

The San Joaquin Valley began to form about 66 million years ago during the early Paleocene era. Broad fluctuations in the sea level caused various areas of the valley to be flooded with ocean water for the next 60 million years.[7] About 5 million years ago, the marine outlets began to close due to uplift of the coastal ranges and the deposition of sediment in the valley. Starting 2 million years ago, a series of glacial episodes periodically caused much of the valley to become a fresh water lake. Lake Corcoran was the last widespread lake to fill the valley about 700,000 years ago. At the beginning of the Holocene there were three major lakes remaining in the southern part of the Valley, Tulare Lake, Buena Vista Lake and Kern Lake. In the late 19th and in the 20th century, agricultural diversion of the Kern River eventually dried out these lakes. Today, only a fragment of Buena Vista Lake remains as two small lakes Lake Webb and Lake Evans in a portion of the former Buena Vista Lakebed.

Climate

[edit]The San Joaquin Valley has extremely hot, dry summers and pleasantly mild winters characterized by dense tule fog.[8] Its rainy season normally runs from November through April. The valley has experienced a severe and intensifying megadrought since the early 2010s. This drought is not only affecting humans, with farmland [9] taking much of the impact, but also the wildlife [10] as well.

In August 2015, the Director of the California Department of Water Resources stated, "Because of increased pumping, groundwater levels are reaching record lows—up to 100 feet lower than previous records."[11] Research from NASA shows that parts of the San Joaquin Valley sank as much as 8 inches (0.20 m) in a four-month period, and land near Corcoran sank 13 inches (0.33 m) in 8 months. The sinking has destroyed thousands of groundwater well casings and has the potential to damage aqueducts, roads, bridges, and flood-control structures. In the long term, the subsidence caused by extracting groundwater could irreversibly reduce the underground aquifer's water storage capacity, although immediate and short term needs are given higher priority and sense of urgency than long term sustainability.[11][12]

The National Weather Service Forecast Office for the San Joaquin Valley is located in Hanford and includes a Doppler weather radar. Weather forecasts and climatological information for the San Joaquin Valley are available from its official website.[13]

Early human settlement

[edit]The San Joaquin Valley was originally inhabited by the Yokuts and Miwok peoples. The first European to enter the valley was Pedro Fages in 1772.[14]

The Tejon Indian Tribe of California is a federally recognized tribe of Kitanemuk, Yokuts, and Chumash indigenous people of California. Their ancestral homeland is the southern San Joaquin Valley, San Emigdio Mountains, and Tehachapi Mountains. Today they live in Kern County, California,[15] headquartered in Wasco and Bakersfield, California.[16]

The Picayune Rancheria of Chukchansi Indians of California is a federally recognized tribe of indigenous people of California, Chukchansi or Foothills Yokuts, now located in Madera County in the San Joaquin Valley.[17] The Santa Rosa Rancheria belongs to the federally recognized Tachi Yokuts tribe and is located 4.5 miles (7.24 km) southeast of Lemoore, California, in the San Joaquin Valley.[18] Since 2010, statewide droughts in California have further strained both the San Joaquin Valley's and the Sacramento Valley's water security.[19][20]

Demographics

[edit]The total population of the eight counties comprising the San Joaquin Valley at the time of the 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-year Estimates by United States Census Bureau reported a population of 4,080,509.[21] The racial composition of San Joaquin Valley was 1,428,978 (35.0%) Non-Hispanic White, 2,048,280 (50.2%) Hispanic or Latino, 310,557 (7.6%) Asian, 193,694 (4.7%) Black or African American, 40,911 (1.0%) American Indian and Alaska Native, and 13,000 (0.32%) Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander.[21]

The educational attainment of high school graduate or higher is 72.7%.[21]

Poverty

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau's American Community Survey, six San Joaquin Valley counties had the highest percentage of residents living below the federal poverty line in 2006 of any counties in California. The report also showed that the same six counties were among the 52 counties with the highest poverty rate in the United States.[22] The median income for a household in the valley was $46,713.[21] The poverty rate for individuals below the poverty level is 23.7%.[21] In 2005 U.S. congressional researchers compared the economically distressed Valley to the traditionally impoverished Appalachia region, resulting in the appellation New Appalachia.[23][24]

In 2011 Forbes, after taking the fluctuation of median home values, five of the top twenty "most miserable cities" were located in the San Joaquin Valley.[25] Aside from the collapse of median home values, persistent crime, unemployment and poverty were common factors between Bakersfield, Fresno, Merced, Modesto and Stockton – every major city of the San Joaquin Valley.

Medical access

[edit]Insufficient access to medicine in the United States, in particular prenatal and preventive care, is typified by both rural and inner city communities. Early and adequate access to prenatal care is important to maternal and child health and is another comparative indicator of community health. According to the California Department of Health Services, 37% of births in Merced County occurred with no or late prenatal care and the San Joaquin Valley average was 19.5% of births with no or late prenatal care. By comparison, the California average was 13.6% of births and the national average was 10% of births[26]

Likewise, the counties of the San Joaquin Valley have relatively high ratios of population to physicians, suggesting relatively low access, with the highest in Kings County at 1,027 patients per a physician, the San Joaquin Valley average at approximately 671 patients per a physician and the California average of 400 patients per a physician.[27] Another measure of access is licensed acute care hospital beds per thousand population, where the Kings County average of 1.1 beds per a thousand and the San Joaquin Valley average of 1.8 beds per a thousand were again less than the state average of 2.1 bed per a thousand.[28] Consequently, the age adjusted death rate is significantly higher than the rest of California.

In response the University of California with the University of California, Merced is exploring opening a research medical school specializing in rural care, in hopes that some graduates will settle in the San Joaquin Valley and provide better healthcare.[29]

Ethnic and cultural groups

[edit]Latinos/Hispanics, Chicanos and Mexicans

[edit]

Currently, the Latino and Mexican descendants are large percentage of the demographics in the San Joaquin Valley. Since not long after the onset of the bracero program during World War II, all but a minor percentage of the farmworkers in the region have been of Mexican ancestry. Ethnic and economic friction between Mexican-Americans and the valley's predominantly white farming elite manifested itself most notably during the 1960s and 1970s, when the United Farm Workers, led by César Chávez, went on numerous strikes and called for boycotts of table grapes. The UFW generated enormous sympathy throughout the United States, even managing to terminate several agricultural mechanization projects at the United States Department of Agriculture. However, from the 1970s onward, landlords and large corporations have also hired undocumented immigrants. This has allowed them to increase their profits due to low overhead on wages.

European groups

[edit]The San Joaquin Valley has—by California standards—an unusually large number of European, Middle Eastern, and Asian ethnicities in the heritage of its citizens. These communities are often quite large and, relative to Americans immigration patterns, quite eclectic: for example, there are more Azorean Portuguese in the San Joaquin Valley than in the Azores. Many groups are found in majorities in specific cities, and hardly anywhere else in the region. For example, Assyrians are concentrated in Turlock, Dutch in Ripon, and Croats[30] in Delano. Kingsburg is famous for its distinctly Swedish air, having been founded by immigrants from that country. Ethnic groups found in a broader area are Portuguese, Germans, Armenians, Basques, and the "Okies" of primarily English and Scots-Irish descent who migrated to California from the Midwest and South. Mennonite groups descended from Russian Germans settled in the areas of Reedley and Dinuba, as well as Lutheran and Catholic Volga Germans who settled in the broader Fresno area.[citation needed]

Asian Americans

[edit]The San Joaquin Valley has a large and exceptionally diverse Asian American population; primarily from the regions of Punjab in India and Pakistan, the Philippines, and Southeast Asia, especially Laos and Cambodia.

Punjabi Sikh Americans have immigrated to the San Joaquin Valley since the early 1900s and 1910s, and remain a very large presence in the area. To this day, Punjabi is the third most spoken language in the San Joaquin Valley region, after English and Spanish,[31] and the first Sikh Gurdwara was founded in Stockton in 1915. Following abolition of immigration restrictions from Asia in the 1960s and 1970s, large numbers of Pakistanis and Indians from Punjab, Gujarat, and Southern India have settled in these valley communities including Modesto, Livingston, Fresno, Stockton, and Lodi.

In addition, the late 1970s and '80s saw an influx of immigrants from Indochina following the War in Vietnam. These immigrants, the majority of whom are Hmong, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese, have largely settled in the communities of Stockton, Modesto, Merced, and Fresno. Hmongs, Laotians, and Cambodians are the largest communities of Southeast Asians in the San Joaquin Valley, and the valley has some of the largest populations of these groups in the nation. Fresno has the second-largest Hmong population of any American metropolitan area after Minneapolis–Saint Paul, and Stockton is believed to have the largest percentage of Cambodian Americans of any major American metropolitan area. Merced, Modesto, Fresno, Visalia, and Stockton have some of the largest populations of Laotian Americans in the United States.

The Filipino American population is concentrated in Delano and Lathrop. Filipinos have a strong history in Stockton. Filipino organizations in Stockton are reflected in various commercial buildings identified as Filipino. Filipinos fought for the U.S. against Japan in WWII, in exchange for favorable immigration status. Stockton has been an adjunct to the San Francisco Bay Area, which was a major military production and transit area during WWII. Filipino emigration to Stockton followed.

African Americans

[edit]Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park marks the location of the only California town to be founded, financed and governed by African Americans. The small farming community was founded in 1908 by Lt. Colonel Allen Allensworth, Professor William Payne, William Peck, a minister, John W. Palmer, a miner, and Harry A. Mitchell, a real estate agent, dedicated to improving the economic and social status of African Americans. Uncontrollable circumstances, including a drop in the area's water table, resulted in the town's demise.

Okies and Arkies

[edit]The Depression-era migrants to the San Joaquin Valley from the South and Midwest are one of the more well-known groups in the Central Valley, in large part due to the popularity of John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath and the Henry Fonda movie made from it. By 1910, agriculture in the southern Great Plains had become nearly unviable due to soil erosion and poor rainfall. Much of the rural population of states such as Kansas, Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas left at this time, selling their land and moving to Chicago, Kansas City, Detroit, and fast-growing Los Angeles. Those who remained experienced continuing deterioration of conditions, which reached their nadir during the drought that began in the late 1920s and created the infamous Dust Bowl. (Small cotton farmers in states such as Mississippi and Alabama suffered similar problems from the first major infestation of the boll weevil.) When the onset of the Great Depression created a national banking crisis, family farmers—usually heavily in debt—often had their mortgages foreclosed by banks desperate to shore up their balance sheets. In response, many farmers loaded their families and portable possessions into their automobiles and drove west.

Many of the Okies and Arkies left the San Joaquin Valley during World War II, most of them going to Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego to work in war-related industries. Many of those who stayed ended up in Bakersfield and Oildale, as the southern San Joaquin Valley became an important area of oil production after major Southern California oil fields such as Signal Hill began to dry up. Country music legends Buck Owens and Merle Haggard came out of Bakersfield's honky-tonk scene and created a hard-driving sound that is still deeply associated with the city.

Economy

[edit]Agriculture

[edit]

The San Joaquin Valley produces 12.8% of California's agricultural production (as measured by dollar value).[32] Often called a breadbasket region, the valley farms emphasize fruits, vegetables and nuts more than grain for bread.[33] Major crops include grapes (wine grapes, table grapes and raisins), cotton, almonds, pistachios, citrus, and vegetables. Walnuts, oranges, peaches, garlic, tangerines, tomatoes, kiwis, hay, alfalfa and numerous other crops have been harvested with great success. Certain places are identified quite strongly with a given crop: Stockton produces the majority of the domestic asparagus consumed in the United States, and Fresno County is the largest producer of raisins.

Cattle and sheep ranching are also vitally important to the valley's economy. During the late 19th century and early 20th century, the Miller & Lux corporation built an agricultural monopoly centered around cattle. The corporation can be characterized as a precursor to corporate farming transforming the yeoman farmer into wage workers. The success of the business can be attributed to founder Henry Miller's direct management style which is reflected in his detailed correspondences to his subordinates.[34] During recent years, dairy farming has greatly expanded in importance. As areas such as Chino and Corona have become absorbed into the suburban sprawl of Los Angeles, many dairy farmers have cashed out and moved their herds to Kings, Tulare, and Kern counties.

Between 1990 and 2004, 28,092 hectares (70,231 acres) of agricultural land was lost to urban development in the San Joaquin Valley.[35] Although there have been some token efforts at confronting the problems of (sub)urban sprawl, the politically conservative climate of the Valley generally prefers traditional suburban sprawl type of growth such as low density housing and strip malls anchored by so-called big box stores and opposes measures such as "Smart Growth", "Transit Oriented Development", "High Density Housing", and increased public transit such as light and commuter rail. By August 2014, a three-year drought was prompting changes to the agriculture industry in the valley. Farmers began using complex irrigation systems and using treated waste water to feed crops, while many were switching from farming cotton to other commodities, chief among them, almonds.[36]

Petroleum

[edit]

California has long been one of the nation's most important oil-producing states, and the San Joaquin Valley has long since eclipsed the Los Angeles Basin as the state's primary oil production region. Scattered oil wells on small oil fields are found throughout the region, and several enormous extraction facilities – most notably near Lost Hills and Taft, including the enormous Midway-Sunset Oil Field, the third-largest oil field in the United States – are veritable forests of pumps.

Shell operated a major refinery in Bakersfield; it was sold in 2005 to Flying J, a Salt Lake-based firm that operates truck stops and refineries. Flying J's bankruptcy in 2009 resulted in the refinery being shut down.[37]

The oil and gas fields in Kern County are receiving increased attention since the July 2009 announcement by Occidental Petroleum of significant discovery of oil and gas reserves[38] Even prior to this discovery the region retains more oil reserves than any other part of California. Of California fields outside of the San Joaquin Valley, only the Wilmington Oil Field in Los Angeles County has untapped reserves greater than 100,000,000 barrels (16,000,000 m3), while six fields in the San Joaquin Valley (Midway-Sunset, Kern River, South Belridge, Elk Hills, Cymric, and Lost Hills) each have reserves exceeding 100,000,000 barrels (16,000,000 m3) of oil.[39]

Other major industries and employers

[edit]The isolation and vastness of the San Joaquin Valley, as well as its poverty and need for jobs, have led the state to build numerous prisons in the area. The most notable of these is Corcoran, whose inmates have included Charles Manson and Juan Corona. Other correctional facilities in the valley are at Avenal, Chowchilla, Tracy, Delano, Coalinga, and Wasco.

The only significant military base in the region is Naval Air Station Lemoore, a vast air base located 25 kilometres (16 mi) WSW of Hanford. Unlike many of California's other military installations, NAS Lemoore's operational importance has increased in the 1990s and 2000s. The other, Castle Air Force Base, located near Atwater was closed during the Base Realignment and Closure of the 1990s. Although both are in Kern County, Edwards Air Force Base and China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station are located in the High Desert area of that county.

Recent changes

[edit]The California real estate boom that began in the late 1990s has significantly changed the San Joaquin Valley. Once distinctly and fiercely independent of Los Angeles and San Francisco, the area has seen increasing exurban development as the cost of living forces young families and small businesses further and further away from the coastal urban cores. Stockton, Modesto, Tracy (as well as the nearby city of Mountain House), Manteca, and Los Banos are increasingly dominated by commuters to San Francisco and Silicon Valley, and the small farming towns to the south are finding themselves in the Bay Area's orbit as well. Bakersfield, traditionally a boom-bust oil town once described by urban scholar Joel Kotkin as an "American Abu Dhabi," has seen a massive influx of former Los Angeles business owners and commuters, to the extent that gated communities containing million-dollar homes are going up on the city's outskirts. Wal-Mart, IKEA, Target, Amazon, CVS Pharmacy, Restoration Hardware, and other various large shipping firms have built huge distribution centers both in the southern end of the valley and northern part of the valley because of quick access to major interstates and low local wages. Further integration with the rest of the state is likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]Roads

[edit]

Interstate 5 (I-5) and State Route 99 (SR 99) each run nearly the entire length of the San Joaquin Valley. I-5 runs in the western part of the valley, bypassing the major population centers (including Fresno, currently the largest U.S. city without an Interstate highway), while SR 99 runs through them. Both highways then merge at the southern end of valley en route to Los Angeles. When the Interstate Highway System was created in the 1950s, the decision was made to build I-5 as an entirely then-new freeway bypass instead of upgrading the then-existing U.S. 99. Since then, state and federal representatives have pushed to convert SR 99 to an Interstate, although this cannot occur until all of the portions of SR 99 between I-5 and the U.S. 50 junction in Sacramento are upgraded to Interstate standards.

State Route 58 (SR 58), which is a freeway in Bakersfield and along most of its route until its terminus in Barstow, is an extremely important and very heavily traveled route for truckers from the valley and the Bay Area who want to cross the Sierra Nevada and leave California (by way of Interstate 15 or Interstate 40) without having to climb Donner Pass or brave the traffic congestion of Los Angeles. Proposals have also been made to designate this highway as a western extension of I-40 once the entirety of the route between Mojave and Barstow has been upgraded to a freeway. This would provide an Interstate connection for Bakersfield, currently the second-largest U.S. city without an Interstate. The most recent additions to this system are State Routes 168 and 180. Route 168 begins in Fresno on Route 180 linking to Huntington Lake in the mountains through Clovis and many smaller communities. This route is part of the California Freeway and Expressway System[citation needed] and is eligible for the State Scenic Highway System.[citation needed] State Route 180 is a state highway which runs through the heart of the San Joaquin Valley from Mendota through Fresno to Kings Canyon National Park. A short piece near the eastern end, through the Grant Grove section of Kings Canyon National Park, is not state-maintained. The part east of unbuilt State Route 65 near Minkler is eligible for the State Scenic Highway System; the road east of Dunlap is the Kings Canyon Scenic Byway, a Forest Service Byway.

Other important highways in the valley include State Route 46 (SR 46) and State Route 41 (SR 41), which respectively link the California Central Coast with Bakersfield and Fresno; State Route 33 (SR 33), which runs south to north along the valley's western rim and provides a connection to Ventura and Santa Barbara over the Santa Ynez Mountains; and State Route 152 (SR 152), an important commuter route linking Silicon Valley with its fast-growing exurbs such as Los Banos.

Air

[edit]

The busiest airport in San Joaquin Valley is the Fresno Yosemite International Airport, which offers scheduled passenger flights to several major airline hubs in the United States and international service to Mexico. Additionally, there are three nonprimary airports in the region: Meadows Field Airport near Bakersfield, Stockton Metropolitan Airport and Merced Municipal Airport.

Rail

[edit]

The San Joaquins service handles passenger traffic between Bakersfield and Stockton with extensions to either Sacramento or Oakland. Amtrak rail service does not continue south of Bakersfield, as the Union Pacific Railroad does not currently allow the San Joaquins trains to run on the highly congested rail route over Tehachapi Pass, which is the only route between Bakersfield and Los Angeles. Passengers between these towns must travel on Amtrak Thruway buses. The San Joaquin Valley is also the location of the planned initial operating segment of the California High-Speed Rail (CAHSR) project, which will run 171 miles from Bakersfield in the south to Merced in the north.

Freight service is provided by BNSF Railway, Union Pacific Railroad and San Joaquin Valley Railroad.[40]

Electricity

[edit]The valley is served by the Western Area Power Administration.[41] Western owns and operates its own equipment here and so performs its own weed management.[41] Rotating and mixing herbicide modes of action are employed to preserve efficacy.[41]

Public health

[edit]Air pollution

[edit]

Hemmed in by mountains and rarely having strong winds to disperse smog, the San Joaquin Valley has long suffered from some of the United States' worst air pollution. In the cooler seasons, this pollution is trapped beneath a layer of warmer air in a phenomenon called temperature inversion, condensing the accumulation of pollutants within the valley[42]. The San Joaquin Valley's air pollution, exacerbated by stagnant weather, comes mainly from diesel and gasoline fueled vehicles and agricultural operations.[43][44] Ammonium nitrate, which forms from the combination of vehicle nitrogen oxides (NOx) and ammonia gas contained in cow manure and urine, "accounts for more than half of the region’s PM2.5 on the area’s most polluted days."[43]

Population growth has caused the San Joaquin Valley to rank with Los Angeles and Houston in most measures of air pollution.[45] Only the Inland Empire region east of Los Angeles has worse overall air quality, and the San Joaquin Valley led the nation in 2004 in the number of days with quantities of ozone considered unhealthy by the Environmental Protection Agency.[45] The San Joaquin Valley has been deemed an "extreme non-attainment zone" by the Environmental Protection Agency, meaning residents are exposed to air quality that is confirmed to be hazardous to human health.[46]

Crop loss

[edit]The region of the San Joaquin Valley has some of the richest soil that allows for the production of many crops.[47] Crops in this region include: grapes, oranges, cotton, vegetables and nuts. The plethora of crop land allows for the valley to benefit from the income of crop sales. About sixty percent of California's crops come from the land in this area.[48] However, the unhealthy air levels that arise from smog lead to the destruction of many crops. According to the California Air Resources Board the San Joaquin Valley loses about one billion dollars every year due to the pollution in the air destroying these crops.[49] Furthermore, as crops and vegetation die off from the air and water quality, farmers sometimes turn to burning to dispose of them. Due to the surplus of crop burning to clear land. more air pollution is created, adding to the severity of the San Joaquin Valley's already poor air quality[50].

Negative effects on public health

[edit]The San Joaquin Valley suffers from extremely high ozone levels that tend to increase even more on hot days.[51] Kids are more inclined to play outdoors during summer when the weather is warmer. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency this could lead to health issues such as asthma because these children are not fully developed yet.[51] The elderly population is also vulnerable to air pollution and could even suffer from heart attacks due to decreased lung functions.[52] Reports state that the residents in this community suffer from high rates of asthma and experience many related symptoms.[53]

Nitrates in groundwater

[edit]San Joaquin Valley is a major agricultural center of California.[54] The agricultural demand for water far outstrips the urban and industrial demand.[55] Overuse of nitrogen fertilizers and irrigated agriculture is common, and according to Thomas Harter, the chair for Water Resources Management and Policy at UC Davis, “more than 80 pounds of nitrogen per acre per year may leach into groundwater beneath irrigated lands, usually as nitrates”.[56] Between the 1950s and 1980s, when nitrogen fertilizer use grew sixfold, nitrate concentrations in groundwater increased 2.5 times.[57] Fertilizer runoffs contributes roughly 90% of all nitrate inputs to the alluvial groundwater system. Within agriculture, the two major factors are High-Intensity Crop Production and Large Dairy Herds.[58] Because these communities are cut off from larger water distribution, they are dependent on wells,[59] making groundwater a source of drinking water for 90% of San Joaquin Valley's residents.[60]

Nitrates have found their way into the aquifers around the San Joaquin Valley, affecting over 250,000 people in communities that are poor and rural.[59] In 2006, the State Water Resources Board took samples from domestic wells in Tulare County; they found that 40% of 181 domestic wells had nitrate levels above the 10 mg/L legal limit.[54] Though locals have typically used filters for their water, the filters need to be installed correctly and replaced frequently, which may not be economically feasible for the residents in Orosi.[61] Table 2 on page 20 from Pacific Institute's "The Human Costs of Nitrate-contaminated Drinking Water in the San Joaquin Valley" indicates the water systems that were contaminated with nitrates over the legal limit, the percentage of the population affected that are non-white and that are below or near poverty-level, and the year since the violations began.[54]

The Turlock Basin is a sub-basin of the San Joaquin Valley groundwater basin found within Stanislaus County and Merced County in the Central Valley.[62] In California's Groundwater Bulletin 118, a chart, linked below, illustrates the number of non-compliant public supply wells with nitrates over the MCL. According to this chart, there were eight wells which had nitrate levels above the 10 mg/L MCL, out of 90 sampled for nitrates in 2006.[62]

Nitrates are of concern because it interferes with the blood's ability to carry oxygen, and can have severe health effects on pregnant women, infants under 6 months, and children using tap water for their formula.[63] Because nitrates interfere with blood's capacity to carry oxygen, infants are at high risk of death from blue-baby syndrome, which can occur when there are high nitrate levels in the blood that are untreated.[63]

High-intensity crop production

[edit]Within the past century, farmers have been increasing their production to meet high demand. To increase output and efficiency, farmers have increased the amount of fertilizers used, including nitrates. Because only a fraction of the nitrogen in fertilizers is efficiently used to help produce crops, this has led to a greater concentration of nitrates and phosphates in the waters, causing eutrophication and contamination of possible drinking water.[64]

Large dairy herds

[edit]Before the rapid rise in demand for meat products and dairy, roaming dairy herds had contributed an insignificant amount of nitrate pollution to the underlying groundwater systems. However, within the past few decades, the increasing amount of cattle has been one of the main contributors of nitrate contamination in the groundwater systems of California.[65] Roughly around 1960, cattle were openly grazing pastures, and because of the large amount of lands which they roamed manure was not intensively managed.[66] However, even though manure was not closely managed, "Nitrogen excretion and deposition in pastures likely did not exceed pasture buffering capacity and had no significant leaching to groundwater".[54] Since the transition to dry-lot and free stall-based dairy farming in the mid-1970s, coupled with irrigated forage crops, dairy herds have contributed to nitrogen contamination.

Possible solutions and alternatives

[edit]The large dairy herds create manure, which is used to create the fertilizers that is applied to the crop fields. As demand for crops increases, farmers look to lower the costs of production. Using manure-based fertilizers is cost effective since manure is a by-product of large dairy farms and herds. The alternative to manure, which contains a high level of nitrates, is composting. Composting however is relatively expensive compared to using manure as fertilizer, since it is not as effective and is more timely/costly to make because of the large amount of aeration needed.[67]

Valley Fever

[edit]Valley Fever, or coccidioidomycosis, is a fungal infection caused by Coccidioides immitis through the inhalation of airborne dust or dirt. The valley is just one of the areas in the southwestern United States where the illness is endemic due to C. immitis residing in the soil.

Cities and counties

[edit]Cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants

[edit]Cities with 100,000 to 500,000 inhabitants

[edit]Cities with 20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants

[edit]Cities with fewer than 20,000 inhabitants

[edit]In popular culture

[edit]The San Joaquin Valley has been a major influence in American country, soul, nu metal, R&B, and hip hop music particularly through the Bakersfield Sound, the Doowop Era, and the Bakersfield Rap Scene, also referred to as Central California Hip Hop, Central Valley Hip Hop, or Central California Rap, which are all subgenres of Gangsta rap, Bass-Rap, West Coast G-funk, and West Coast Hip hop which are all different styles of West Coast Rap.[68] The Valley has been the home to many country, nu metal, and doo-wop musicians and singers, such as Buck Owens, Merle Haggard, Billy Mize, Korn, Red Simpson, Dennis Payne, Tommy Collins, The Maddox Brothers and Rose, The Paradons, The Colts, and the Sons of the San Joaquin.[69] The San Joaquin Valley is also home to many Indie Hip Hop labels, R&B singers, Jazz & Funk musicians, and Hip Hop artist such as: Kottonmouth Kings,Fashawn, Killa Tay, The Def Dames, Cali Agents, Planet Asia.[70] The Valley also has a strong literary tradition, heavy in poetry, producing many famous poets such as Sherley Anne Williams, and Gary Soto, former U.S. Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera, and David St. John.[71]

See also

[edit]- Groundwater-related subsidence

- List of California rivers

- Sacramento Valley

- San Joaquin (soil)

- Water in California

References

[edit]- ^ Righter, Robert W. (2005). The Battle over Hetch Hetchy: America's Most Controversial Dam and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism. Oxford University Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780199882069.

- ^ "San Joaquin Valley Fact Sheet". Valley Clean Air Now. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

Eight counties comprise the San Joaquin Valley, including all of Kings County, most of Fresno, Kern, Merced, and Stanislaus counties, and portions of Madera, San Luis Obispo, Tulare counties

- ^ Carle, David (2006). Introduction to Air in California. University of California Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780520247482.

- ^ a b Agricultural Drainage and Salt Management in the San Joaquin Valley: A Special Report Including Recommended Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Report. San Joaquin Valley Interagency Drainage Program. 1979. p. 2.1.

The San Joaquin Valley, measuring about 250 miles (400 kilometres) by 40 to 60 miles (65 to 95 km), is the southern half of the great Central Valley of California.

- ^ Passenger Department, Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway Company (1902). The San Joaquin Valley of the State of California: A Brief Description of the Topography, Climatic Conditions, Industrial Development and Resources of the Region : Illustrated by Photographs of Typical Scenes and Containing Maps. Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. pp. 9–10.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Taylor, Nathaniel R. (1913). The Rivers and Floods of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Watersheds. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 39.

The San Joaquin Valley is bounded on the east by the Sierra Nevada, on the south by the Tehachapi Cross Range, on the west by the Coast Range; in the north it merges into the Sacramento Valley in the region of the Mokelumne and Cosumnes Rivers.

- ^ Rose David, Lore (1946). Upper Cretaceous Fish Remains from the Western Border of the San Joaquin Valley, California. Vol. 551. Washington D.C.: Fossil Vertebrates from Western North America and Mexico. pp. 81–112. OCLC 11426561.

- ^ Office of Governmental and Public Affairs (1978). People on the Farm: Growing Oranges. United States Department of Agriculture. p. 24.

- ^ Helalia, Sarah A.; Anderson, Ray G.; Skaggs, Todd H.; Šimůnek, Jirka (December 2021). "Impact of Drought and Changing Water Sources on Water Use and Soil Salinity of Almond and Pistachio Orchards: 2. Modeling". Soil Systems. 5 (4): 58. doi:10.3390/soilsystems5040058. ISSN 2571-8789.

- ^ Barbaree, Blake A.; Reiter, Matthew E.; Hickey, Catherine M.; Strum, Khara M.; Isola, Jennifer E.; Jennings, Scott; Tarjan, L. Max; Strong, Cheryl M.; Stenzel, Lynne E.; Shuford, W. David (October 21, 2020). "Effects of drought on the abundance and distribution of non-breeding shorebirds in central California, USA". PLOS ONE. 15 (10): e0240931. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1540931B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240931. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7577470. PMID 33085697.

- ^ a b "NASA Report: Drought Causing Valley Land to Sink" (PDF). California Department of Water Resources. August 19, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ "NASA: California Drought Causing Valley Land to Sink". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. August 19, 2015. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ "San Joaquin Valley/Hanford, CA". National Weather Service Forecast Office. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Capace, Nancy (1999). Encyclopedia of California. North American Book Dist LLC. Page 410. ISBN 9780403093182.

- ^ Edelhart, Courtenay. (March 5, 2012). "Tejon tribe fought for recognition throughout history". The Bakersfield Californian. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013. Alt URL

- ^ "Tejon Indian Tribe Gains Federal Reaffirmation". Native News Network. January 4, 2011. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ California Indians and Their Reservations: Y. San Diego State University Library and Information Access. 2009 (retrieved 29 June 2010)

- ^ "Welcome to Tachi Palace Hotel and Casino". Tachi Palace Hotel & Casino. Tachi Palace. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ "Groundwater Management and Drought: An Interview with the San Joaquin Valley Partnership". water.ca.gov. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ^ MICHAEL MCGOUGH (April 29, 2022). "Southern California gets drastic water cutbacks amid drought. What's next for Sacramento?". amp.sacbee.com. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Fresno Bee, August 29, 2007

- ^ [1] San Joaquin Valley: New Appalachia?

- ^ "Poverty plagues 'new Appalachia'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ [2] America's Most Miserable Cities

- ^ [3] San Joaquin Valley: Land, People, and Economy

- ^ San Joaquin Valley: Land, People, and Economy. http://www.library.ca.gov/crb/05/07/05-007.pdf

- ^ San Joaquin Valley: Land, People, and Economy. http://www.library.ca.gov/crb/05/07/05-007.pdf

- ^ [4] UC Merced and UC Davis Partner to Begin Educating Medical Students in the Valley

- ^ On rich soil: Kern County families provide grapes aplent Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, The Bakersfield Californian, By Jeff Nickell, Saturday, Jun 30, 2012 12:00 AM

"...Marin Caratan than he was the first Croatian to come to the area to grow grapes...said Mark Zaninovich ..., but it is also fair to mention the Carics, Jakoviches, Radoviches, Bozaniches, Buskas, Sousas, Kovacaviches, Bidarts, Sandrinis, and Paviches." - ^ Sewell, Summer (February 8, 2021). "'This has to end peacefully': California's Punjabi farmers rally behind India protests". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ 2007 Overview - Agricultural Statistical Review Archived 2009-05-02 at the Wayback Machine - California Agricultural Resource Directory 2008–2009

- ^ Palmer, Tim (1982). Stanislaus: The Struggle for a River. University of California Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 9780520052253.

- ^ Henry Miller Papers Collection, "Correspondence to Superintendent Turner," 18 July 1912, Special Collections, Henry Madden Library, California State University, Fresno

- ^ Paving Paradise: A New Perspective on California's Farmland Conversion, American Farmland Trust, November 2007

- ^ "California drought will affect the global agriculture industry". Los Angeles News.Net. August 17, 2014. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ "Big West to Suspend Operations at its Refinery on Rosedale Highway". KGET News. January 28, 2009. Archived from the original on June 12, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Occidental Announces Major Oil and Gas Discovery in Kern County". California Energy News. July 23, 2009. Archived from the original on October 9, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- ^ 2006 California Department of Conservation, 2006 Oil and Gas Statistics Archived 2017-05-25 at Archive-It, p. 4

- ^ Lustig, David (April 2023). "VALLEY FEVER". Trains. Kalmbach Media. pp. 22–29.

- ^ a b c Tuggle, Stephen (June 2010), Draft Environmental Assessment for Right-of-Way Maintenance in the San Joaquin Valley, California, US Department of Energy, Western Area Power Administration, Sierra Nevada Region, pp. vii + 259 + 227 appendices, DOE/EA-1697

- ^ Borrell, Brendan (December 3, 2018). "In California's Fertile Valley, Industry Hangs Heavy in the Air". Undark Magazine. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Borrell, Brendan (December 3, 2018). "In California's Fertile Valley, a Bumper Crop of Air Pollution". Undark. Archived from the original on September 27, 2019. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ Carle 2006, pp. 97–98

- ^ a b Bustillo, Miguel (November 14, 2008) L.A.'s the Capital of Dirty Air Again Los Angeles Times

- ^ Richter, Lauren (December 19, 2017). "Constructing insignificance: critical race perspectives on institutional failure in environmental justice communities". Environmental Sociology. 4: 107–121. doi:10.1080/23251042.2017.1410988. S2CID 7434845.

- ^ Parsons, James J. (1986). "A Geographer Looks at the San Joaquin Valley". Geographical Review. 76 (4): 371–389. Bibcode:1986GeoRv..76..371P. doi:10.2307/214912. JSTOR 214912.

- ^ Kim, Hong Jin; Helfand, Gloria E.; Howitt, Richard E. (1998). "An Economic Analysis of Ozone Control in California's San Joaquin Valley". Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics. 23 (1): 55–70. JSTOR 40986967.

- ^ "San Joaquin Valley Air Quality Study Final Report Released".

- ^ Briscoe, Tony (June 11, 2022). "Air quality worsens as drought forces California growers to burn abandoned crops". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ a b "Fact Sheet: Overview of EPA's Updates to the Air Quality Standards" (PDF).

- ^ "Disease Control and Prevention: Air Pollution".

- ^ Meng, Ying-Ying; Rull, Rudolph P.; Wilhelm, Michelle; Lombardi, Christina; Balmes, John; Ritz, Beate (2010). "Outdoor Air Pollution and Uncontrolled Asthma in the San Joaquin Valley". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 64 (2): 142–147. doi:10.1136/jech.2009.083576. JSTOR 20721155. PMID 20056967. S2CID 21251437.

- ^ a b c d Pacific Institute (March 2011). "The Human Costs of Nitrate-contaminated Water in the San Joaquin Valley" (PDF). Pacific Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2017.

- ^ Cody, Betsy A. (2010). California Drought: Hydrological and Regulatory Water Supply Issues. DIANE Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 9781437927573.

- ^ Harter, Thomas (2009). "Agricultural Impacts on Groundwater Nitrate" (PDF). Southwest Hydrology. 8: 22–23. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ "Groundwater Shock: The Polluting of the World's Major Freshwater Stores | Worldwatch Institute". www.worldwatch.org. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ Agence France-Presse (September 20, 2016). "Nitrates poison water in California's Central Valley". Yahoo! News. Associated Newspapers Ltd. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ a b AFP (September 19, 2016). "Nitrates Poison Water in California's Central Valley". Community Water Center. Archived from the original on May 5, 2017.

- ^ Community Water Center (December 2013). "Water & Health in the Valley: Nitrate Contamination of Drinking Water and the Health of San Joaquin Valley Residents" (PDF). Community Water Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2017.

- ^ Carroll, Gerald (November 14, 2006). "Tulare County Private Wells Test High for Nitrates" (PDF). Visalia Times-Delta. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2017.

- ^ a b water.ca.gov (April 11, 2017). "California's Groundwater Bulletin 118" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2017.

- ^ a b "Nitrates and Nitrites" (PDF). EPA. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 21, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Burow, Karen. "Assessment of regional change in nitrate concentrations in groundwater in the Central Valley, California, USA, 1950s–2000s" (PDF). Ca Water Usgs. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 30, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ Moore, Eli. "Human Costs of Nitrate-contaminated Drinking Water in the San Joaquin Valley" (PDF). Pacific Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Burow, Karen. "Assessment of regional change in nitrate concentrations in groundwater in the Central Valley, California, USA, 1950s–2000s" (PDF). Ca Water Usgs. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 30, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ Gamroth, Mike. "Composting: An Alternative for Livestock Manure Management and Disposal of Dead Animals" (PDF). Oregon State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ Central California Hip Hop Archived 2015-04-04 at the Wayback Machine sites.google.com 04-05-2015 Retrieved. 04-05-2015

- ^ “The Colts” by (JIM DAWSON) Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine www.electricearl.com 14-05-2015 Retrieved. 14-05-2015

- ^ The Def Dames- Billboard Hot 100 Carts Archived 2016-01-06 at the Wayback Machine www.billboard.com 14-05-2015 Retrieved. 14-05-2015

- ^ Sherley Ann Williams – Poetry Soup Archived 2015-05-18 at the Wayback Machine www.poetrysoup.com 14-05-2015 Retrieved. 14-05-2015

External links

[edit]- San Joaquin Valley

- Valleys of California

- Regions of California

- San Joaquin River

- Valleys of Fresno County, California

- Valleys of Kern County, California

- Valleys of Kings County, California

- Valleys of Madera County, California

- Valleys of Merced County, California

- Valleys of San Joaquin County, California

- Valleys of Stanislaus County, California

- Valleys of Tulare County, California

- Geography of the Central Valley (California)