Lysander

Lysander | |

|---|---|

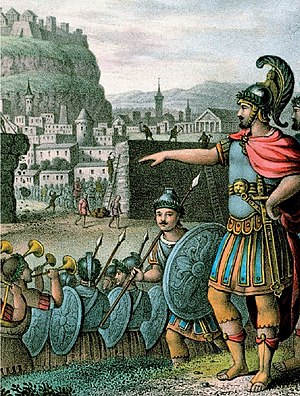

Lysander outside the walls of Athens, ordering their destruction. 19th century lithograph. | |

| Native name | Λύσανδρος |

| Born | c. 454 BC[1] |

| Died | 395 BC (aged c. 59) (2418 years ago) Haliartus |

| Allegiance | Sparta |

| Rank | Navarch |

| Battles / wars | |

Lysander (/laɪˈsændər, ˈlaɪˌsændər/; Greek: Λύσανδρος Lysandros; c. 454 BC – 395 BC) was a Spartan military and political leader. He destroyed the Athenian fleet at the Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC, forcing Athens to capitulate and bringing the Peloponnesian War to an end. He then played a key role in Sparta's domination of Greece for the next decade until his death at the Battle of Haliartus.

Lysander's vision for Sparta differed from most Spartans; he wanted to overthrow the Athenian Empire and replace it with Spartan hegemony.[2]

Early life

[edit]Little is known of Lysander's early life. His year of birth is estimated at 454 BC.[1] Some ancient authors record that his mother was a helot or slave.[3] Lysander's father was Aristocritus,[4] who was a member of the Spartan Heracleidae; that is, he claimed descent from Heracles but was not a member of a royal family. According to Plutarch, Lysander grew up in poverty and showed himself obedient, conformed to norms, and had a "manly spirit".[5]

It was custom in the Spartan upbringing for a young adult to be assigned as the "inspirer" (eispnelas) or "lover" (erastes) of an adolescent, and Lysander was matched in this role with the future king Agesilaus, the younger son of Archidamus II.[6] Nothing is known of Lysander's actual career before he was elected, in 408 BC, to Sparta's annual office of admiral, to conduct the long-running Peloponnesian War against Athens.[7]

Admiral

[edit]

From Gythium on the eastern shore of the Peloponnese, Lysander set out with 30 triremes. He sailed to Rhodes, where he collected some more ships, and made his way to Cos, Miletus, Chios, gathering ships, until he finally arrived at Ephesus, which he turned into the Peloponnesian League's main naval base for the Aegean.[9] His arrival was shortly followed by that of Cyrus, young son of the Persian king Darius, who had been appointed by his father as governor of the provinces of Asia Minor in response to an earlier Spartan embassy requesting increased aid in the war against Athens. Lysander promptly went to meet Cyrus at his headquarters in nearby Sardis, and with calculated deference made a deep impression on the young prince, developing with him a close friendship that was to have a decisive effect in the course of the war.[10] Cyrus began funding Sparta's war effort on a large scale, and was encouraged to increase the pay of Lysander's crews from three to four obols, increasing their morale and Lysander's popularity among them.[11] Once back in Ephesus, Lysander summoned a conference of influential oligarchs from all over the Greek cities in the Aegean, encouraged them to organize into political clubs (hetaireiai), and promised to put them in power in their respective cities in the event of Athens' defeat. In doing so, Lysander created in effect a network of clients who were loyal to him personally and contributed to Sparta's war effort with increased eagerness.[12]

As Lysander was fitting out his vessels at Ephesus, an Athenian fleet roughly the size of his own, led by the famous Alcibiades, set up anchor at the nearby port of Notium.[13] At first, the Spartan was content to refuse battle and let his higher wages, funded by Cyrus, encourage desertions among the enemy crews.[14] Eventually, however, one of the Athenian officers, despite orders to stay put, was drawn into a fight with an advance party of Peloponnesian ships. Lysander gave a timely order for his entire fleet to advance, and drove off the intruder before they had properly deployed for battle, inflicting modest losses.[15] Alcibiades, who had been away on urgent business, returned upon hearing of this setback and again offered battle off Ephesus, but Lysander once more refused, and the Athenians had to withdraw.[16]

However, Lysander ceased to be the Spartan navarch after this victory and, in accordance with the Spartan law, was replaced by Callicratidas. Callicratidas' ability to continue the war at sea was neatly sabotaged when Lysander returned all the donated funds to Cyrus when he left office.[17]

Vice-admiral

[edit]After Callicratidas was defeated and killed at the Battle of Arginusae, Cyrus and the oligarchic clubs which Lysander had sponsored all sent embassies to Sparta requesting the former admiral's return to command. The Spartan government consented, a sign of confidence in his ability and an endorsement of his policy of supporting oligarchies in the Greek cities.[18] As Spartan law did not allow an admiral to hold office twice, Lysander was instead appointed the secretary (epistoleus) or second-in-command to Callicratidas's eventual successor, Aracus, with the understanding that the latter would allow Lysander to take the lead.[19] Making his base at Ephesus again, the Spartan began gathering and rebuilding the remnants of the Peloponnesian fleet in the Aegean, once again with the full cooperation of his Greek allies and Cyrus.[20] In the meantime, Lysander visited Miletus, an ally of Sparta, and deceitfully massacred some leading democrats during the festival of Dionysus in early 405 BC to place his own adherents in power; replacing Miletus' democracy with an Oligarchy.[21] In the summer, Lysander's principal benefactor, Cyrus, was summoned to the deathbed of his father, the King, and, before departing, took the extraordinary step of entrusting the Spartan with his entire treasury and with the revenues from the Persian-ruled cities under his administration.[22]

Lysander finally set sail with some 125–150 ships, and among his early actions, which are variously reported by the sources, were the massacre and enslavement of the population of Iasus and Cedreae, allies of Athens. He continued toward the Hellespont to threaten the route of grain transports to Athens from the Black Sea, forcing the Athenians to send their fleet, 180 ships, in pursuit. Lysander set up anchor at Lampsacus and plundered it, while the Athenians took up a position at Aegospotami in the opposing shore of the straits. For several days Lysander refused battle, studying the opponent's moves, until, during a moment of enemy carelessness, he surprised the Athenians and captured most of their vessels as they were still ashore and unmanned. The entire Athenian fleet was gone, and Sparta had finally won the Peloponnesian War.[23]

Now in full command of the seas, Lysander began touring the Aegean to receive the surrender of enemy strongholds, ordering all captured Athenian garrisons and cleruchs (colonists) home in order to overcrowd the city and hasten its surrender through famine.[24] In many Greek cities, he installed ten-man governing boards (decarchies) whose members were selected from the oligarchic clubs he had sponsored earlier, supported and supervised by a Spartan harmost (military governor).[25] Democrats and other opponents of his narrow oligarchies were often massacred or banished.[26] In a propaganda gesture he restored places like Aegina, Melos and Scione to populations whom the Athenians had forcibly uprooted throughout the course of the war.[27]

Following an unsuccessful attempt to bring about Athens's surrender with a show of force off Attica in autumn 405 BC, Lysander began establishing contacts with Athenian oligarchic exiles and sponsored their return to the city as one of the conditions for peace,[28] which was finally concluded in spring 404 BC. Lysander received the surrender of the last of Athens's allies, Samos, in the summer of 404 BC, after which he went in person to Athens in response to an appeal by Athenian oligarchs. On the anniversary of the Battle of Salamis, Lysander sailed into the Piraeus, ordered the razing of Athens's city walls and the burning of its fleet, and sent for female flautists from the city to play music as the deed was carried out. He also oversaw a meeting of the Athenian assembly which effectively abolished Athens's democracy and replaced it with a governing board of thirty oligarchs (the Thirty Tyrants).[29]

Command in Athens

[edit]

After storming and seizing Samos, Lysander returned to Sparta. Alcibiades, the former Athenian leader, emerged after the Spartan victory at Aegospotami and took refuge in Phrygia, northwestern Asia Minor with Pharnabazus, its Persian satrap. He sought Persian assistance for the Athenians. However, the Spartans decided that Alcibiades must be removed and Lysander, with the help of Pharnabazus, arranged the assassination of Alcibiades.[5][30]

Lysander amassed a huge fortune from his victories against the Athenians and brought the riches home to Sparta. For centuries the possession of money was illegal in Lacedaemonia, but the newly minted navy required funds and Persia could not be trusted to maintain financial support. Roman historian Plutarch strongly condemns Lysander's introduction of money;[5] despite being publicly held, he argues its mere presence corrupted rank-and-file Spartans who witnessed their government's newfound value for it. Corruption quickly followed; while general Gylippus ferried treasure home, he embezzled a great amount and was condemned to death in absentia.

Resistance by Athens

[edit]The Athenian general Thrasybulus, who had been exiled from Athens by the Spartans' puppet government, led the democratic resistance to the new oligarchic government. In 403 BC, he commanded a small force of exiles that invaded Attica and, in successive battles, defeated first a Spartan garrison and then the forces of the oligarchic government (which included Lysander) in the Battle of Munychia. The leader of the Thirty Tyrants, Critias, was killed in the battle.

The Battle of Piraeus was then fought between Athenian exiles who had defeated the government of the Thirty Tyrants and occupied Piraeus and a Spartan force sent to combat them. In the battle, the Spartans defeated the exiles, despite their stiff resistance. Despite opposition from Lysander, after the battle Pausanias the Agiad King of Sparta, arranged a settlement between the two parties which allowed the re-establishment of democratic government in Athens.

Final years

[edit]Lysander still had influence in Sparta despite his setbacks in Athens. He was able to persuade the Spartans to select Agesilaus II, his younger lover,[31][32] as the new Eurypontid Spartan king following the death of Agis II, and to persuade the Spartans to support Cyrus the Younger in his unsuccessful rebellion against his older brother, Artaxerxes II of Persia.

Hoping to restore the juntas of oligarchic partisans that he had put in place after the defeat of the Athenians in 404 BC, Lysander arranged for Agesilaus II, the Eurypontid Spartan king, to take command of the Greeks against Persia in 396 BC. The Spartans had been called on by the Ionians to assist them against the Persian King Artaxerxes II. Lysander was arguably hoping to receive command of the Spartan forces not joining the campaign. However, Agesilaus had become resentful of Lysander's power and influence. So Agesilaus frustrated the plans of his former mentor and left Lysander in command of the troops in the Hellespont, far from Sparta and mainland Greece.

Back in Sparta by 395 BC, Lysander was instrumental in starting a war with Thebes and other Greek cities, which came to be known as the Corinthian War. The Spartans prepared to send out an army against this new alliance of Athens, Thebes, Corinth and Argos (with the backing of the Achaemenid Empire) and ordered Agesilaus to return to Greece. Agesilaus set out for Sparta with his troops, crossing the Hellespont and marching west through Thrace.

Death

[edit]The Spartans arranged for two armies, one under Lysander and the other under Pausanias of Sparta, to rendezvous at and attack the city of Haliartus in Boeotia. Lysander arrived before Pausanias and persuaded the city of Orchomenus to revolt from the Boeotian League. He then advanced to Haliartus with his troops. In the Battle of Haliartus, Lysander was killed after bringing his forces too near to the walls of the city.

Following Lysander's death, Agesilaus II "discovered" an abortive scheme by Lysander to increase his power by making the Spartan kingships collective and that the Spartan king should not automatically be given the leadership of the army.[5][33] There is argument amongst historians as to whether this was an invention to discredit Lysander after his death. However, in the view of Nigel Kennell, the plot fits with what we know of Lysander.[34]

Legacy

[edit]Lysander is one of the main protagonists of the history of Greece by Xenophon, a contemporary. For other (later) sources he remains an ambiguous figure. For instance, while the Roman biographer Cornelius Nepos charges him with "cruelty and perfidy",[33] Lysander – according to Xenophon – nonetheless spared the population of captured Greek poleis such as Lampsacus.[30]

The Westland Lysander aircraft was named after him.

Commemoration

[edit]According to Duris of Samos, Lysander was the first Greek to whom the cities erected altars and sacrificed to him as to a god and the Samians voted that their festival of Hera should be called Lysandreia.[35] He was also the first Greek who had songs of triumph written about him.[5]

Sayings attributed to Lysander

[edit]- "Where the lion's skin does not reach, it must be patched with the fox's".[5]

- He boasted about cheating "boys with knuckle-bones and men with oaths".[5]

Sources

[edit]- Bommelaer, Jean-François (1981). Lysandre de Sparte. Histoire et traditions (in French). Paris: De Boccard.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Detlef Lotze, Lysander und der Peloponnesische Krieg, Berlin: Akademie (1964), 13

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire, Cornell University, 1987, p. 300. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Smith, William (1867). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. Boston: Little, Brown and co. p. 861.

- ^ Mitchell, Lynette G. (2002). Greeks Bearing Gifts: The Public Use of Private Relationships in the Greek World, 435–323 BC. Cambridge University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-521-89330-5.. Some manuscript sources have "Aristocleitus", but "Aristocritus" appears in contemporary inscriptions, e.g. Inscriptiones Graecae II2 1388, l. 32.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Plutarch, Lives. Life of Lysander. (University of Massachusetts/Wikisource)

- ^ Paul Cartledge, Agesilaos and the Crisis of Sparta, London: Duckworth, 1987, 29

- ^ Paul Cartledge, Agesilaos and the Crisis of Sparta, London: Duckworth, 1987, 79

- ^ Rollin, Charles (1851). The Ancient History of the Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Grecians, and Macedonians. W. Tegg and Company. p. 110.

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, 301

- ^ Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 36, 37; Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, 305–306

- ^ Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 37

- ^ Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 37–38; Paul Cartledge, Agesilaos and the Crisis of Sparta, London: Duckworth, 1987, 81; Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, 306–307

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, 310

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, 310–311

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, 317–318, 319

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, 318

- ^ "Spartans, a new history", Nigel Kennell, 2010, p. 126

- ^ Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 38, 39, 60

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, 380

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, 380- 381; Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 39

- ^ Paul Cartledge, Agesilaos and the Crisis of Sparta, London: Duckworth, 1987, 91; Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, 382–383

- ^ Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 39

- ^ Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, 385–386; Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 40

- ^ Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 43, 45, 163

- ^ Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 44, 59

- ^ Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 65, 85; Paul Cartledge, Agesilaos and the Crisis of Sparta, London: Duckworth, 1987, 91, 93

- ^ Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 44; Nigel M. Kennell, Spartans: A New History, Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, 202

- ^ Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979, 62–63; Mark Munn, The School of History: Athens in the Age of Socrates, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000, 204, 407 (note 22)

- ^ Mark Munn, The School of History: Athens in the Age of Socrates, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000, 220

- ^ a b c Xenophon, Hellenica. (Wikisource/Gutenberg Project)

- ^ Cartledge, Agesilaos, pp. 28, 29.

- ^ Hamilton, Agesilaus, p. 19.

- ^ a b Cornelius Nepos, Life of Eminent Greeks .[1]

- ^ "Spartans, a new history", Nigel Kennell, 2010, p. 134

- ^ The Hellenistic World by Frank William Walbank Page 213 ISBN 0-674-38726-0

External links

[edit]- Ancient/classical history (Lysander) – About.com

- Lysander by Plutarch – The Internet Classics Archive on MIT