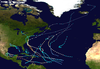

1955 Atlantic hurricane season

| 1955 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | July 31, 1955 |

| Last system dissipated | October 19, 1955 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Janet |

| • Maximum winds | 175 mph (280 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 914 mbar (hPa; 26.99 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 13 [nb 1] |

| Total storms | 13 [nb 1] |

| Hurricanes | 9 [nb 1] |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 4 |

| Total fatalities | 1,601 total |

| Total damage | ~ $1.11 billion (1955 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The 1955 Atlantic hurricane season was, at the time, the costliest season ever recorded, just ahead of the previous year. The hurricane season officially began on June 15, 1955, and ended on November 15, 1955. It was an extremely active season in terms of accumulated cyclone energy (ACE), but only slightly above average in terms of storm formation, with 13 recorded tropical cyclones.

The first reported system of the year, January's Hurricane Alice, was later found to have formed on December 30, during the 1954 season. Alice caused relatively minor impact as it tracked through the Lesser Antilles and eastern Caribbean Sea. The first tropical cyclone to form in 1955, Tropical Storm Brenda, caused two deaths and minor damage along the Gulf Coast of the United States in early August. The quick succession of Hurricanes Connie and Diane caused significant flooding in the Northeastern United States, with nearly $1 billion (1955 USD, $11.05 billion in 2022 USD) in losses and at least 232 fatalities. The next three storms, Hurricanes Edith and Flora, along with Tropical Storm Five, caused very minor or no impact. In early September, Hurricane Gladys caused severe localized flooding in Mexico, primarily in Mexico City. Additionally, an offshoot of Gladys inflicted minor impact in Texas.

Hurricane Hilda struck the Greater Antilles and then Mexico. It was attributed to at least 304 deaths and $120 million in losses. In mid-September, Hurricane Ione struck eastern North Carolina and contributed the flooding from Connie and Diane, resulting in seven fatalities and $88 million in damage. Later that month, Hurricane Janet, which peaked as a Category 5 hurricane, lashed several countries adjacent to the Caribbean Sea, as well as Mexico and British Honduras. Janet resulted in $53.8 million in damage and at least 716 deaths. An unnamed tropical storm in the month of October did not impact land. Hurricane Katie, the final storm, caused minor damage in a sparsely populated area of Hispaniola, totaling to at least $200,000; 7 fatalities were also reported.

Collectively, the storms this year caused 1,601 deaths and $1.11 billion in losses, making it the costliest season at the time. Afterward, a then‑record four storm names were retired.

Season summary

[edit]

On April 11, 1955, which was prior to the start of the season, Gordon Dunn was promoted to the chief meteorologist of the Miami Hurricane Warning Office. Dunn was replacing Grady Norton, who died from a stroke while forecasting Hurricane Hazel of the previous season.[1] In early June, the Hurricane Hunters received new reconnaissance aircraft, which contained the latest radar and electronic equipment, at the time.[2] Later that month, shortly before the start of the 1955 season, a bill was proposed in the United States Senate to provide funding for 55 new radar stations along the East Coast of the United States. After the United States House of Representatives passed a bill allotting $5 million, the Senate disputed about possibly increasing the funding two-fold to $10 million.[3] Eventually, the radars were installed, starting in July 1955.[4] After the devastating storms of the season, particularly Connie and Diane, a United States Government organization with the purpose of monitoring tropical cyclones was established in 1956 with $500,000 in funding; it later became the modern-day National Hurricane Center.[5]

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 15, 1955.[6] It was an above average season in which 13 tropical cyclones formed. In a typical season, about nine tropical storms develop, of which five strengthen to hurricane strength. All thirteen depressions attained tropical storm status, and eleven of these attained hurricane status.[4] Six hurricanes further intensified into major hurricanes.[7] The season was above average most likely because of a strong, ongoing La Niña.[8] Hurricane Alice was named in January 1955 but was operationally analysed to have developed in late December 1954.[9] Within the official hurricane season bounds, tropical cyclogenesis did not occur until July 31, with the development of Tropical Storm Brenda. However, during the month of August, four tropical cyclones formed – including Connie, Diane, Edith, and an unnamed tropical storm. Five additional tropical cyclones – Flora, Gladys, Hilda, Ione, and Janet – all developed in September. Tropical cyclogenesis briefly halted until an unnamed tropical storm formed on October 10.[4] The final storm of the season, Katie, dissipated on October 19,[7] almost a month before the official end of hurricane season on November 15.[6] Eight hurricanes and two tropical storms made landfall during the season and caused 1,603 deaths and $1.1 billion in damage.[4]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 158,[10] which was well above the 1950-2000 average of 96.1. ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical cyclones with winds exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is tropical storm strength.[11]

Systems

[edit]Tropical Storm Brenda

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 31 – August 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); ≤995 mbar (hPa) |

The first tropical depression of the season formed in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico early on July 31. Six hours later, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Brenda. During the next 24 hours, the storm strengthened and attained its peak intensity of 70 mph (110 km/h) early on August 1 before making landfall in New Orleans, Louisiana, at a slightly weaker intensity of 65 mph (105 km/h). The storm steadily weakened inland and at 0600 UTC on August 2, it was downgraded to a tropical depression. About 24 hours later, Brenda dissipated while located over northeastern Texas.[7]

Between Pensacola, Florida, and Lake Charles, Louisiana, rainfall totals were generally about 4 inches (100 mm); flooding, if any, was insignificant. Tropical storm force winds were reported, peaking at 50 mph (80 km/h) at Shell Beach, Louisiana, on the south shore of Lake Borgne. At the same location, tides between 5 and 6 feet (1.5 and 1.8 m) above normal were measured.[4] Four people were rescued by the United States Coast Guard after their tugboat sank in Lake Pontchartrain, while three others swam to shore.[12] Additionally, two fatalities occurred in the vicinity of Mobile, Alabama.[4]

Hurricane Connie

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 3 – August 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min); 944 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression east of Cape Verde on August 3.[4] After six hours, it strengthened into Tropical Storm Connie.[7] By August 4, Connie began to rapidly strengthen, becoming the first major hurricane of the season later that day. Initially, it posed a threat to the Lesser Antilles, although it passed about 50 miles (80 km) north.[4][7] The outer rainbands produced hurricane-force wind gusts and intense precipitation, reaching 8.65 inches (220 mm) in Puerto Rico.[13] In the United States Virgin Islands, three people died due to the hurricane, and a few homes were destroyed. In Puerto Rico, Connie destroyed 60 homes and caused crop damage.[14] After affecting Puerto Rico, Connie turned to the northwest, reaching peak winds of 140 mph (230 km/h).[7] The hurricane weakened while slowing and turning to the north, and struck North Carolina on August 12 as a Category 2 hurricane.[4]

Connie produced strong winds, high tides, and heavy rainfall as it moved ashore, causing heavy crop damage and 27 deaths in the state of North Carolina.[4][15] Connie made a second landfall in Virginia,[15] and it progressed inland until dissipating on August 15 near Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. Connie is noted for being the only hurricane in recorded history to strike Michigan/the Great Lakes region as a tropical storm.[7] Four people were killed in Washington, D.C. due to a traffic accident.[16] In the Chesapeake Bay, Connie capsized a boat, killing 14 people and prompting a change in Coast Guard regulation.[17] There were six deaths each in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and eleven deaths in New York,[18] where record rainfall flooded homes and subways.[19] At least 225,000 people lost power during the storm.[20] Damage in the United States totaled around $86 million,[21] although the rains from Connie was a prelude to flooding by Hurricane Diane.[4] The remnants of Connie destroyed a few houses and boats in Ontario and killed three people in Ontario.[22]

Hurricane Diane

[edit]| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 7 – August 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 969 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave spawned a tropical depression between the Lesser Antilles and Cape Verde on August 7.[4][7] It slowly strengthened and became Tropical Storm Diane on August 9.[7] After a Fujiwhara interaction with Hurricane Connie, Diane curved northward or north-northeastward and quickly deepened.[4] By early on August 8, the storm was upgraded to a hurricane. Only several hours later, Diane peaked as a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h).[7] The storm resumed its west-northwestward motion on August 13. Colder air in the region caused Diane to weaken while approaching the East Coast of the United States. A recently installed radar in North Carolina noted an eye feature, albeit poorly defined. Early on August 17, Diane made landfall near Wilmington, North Carolina, as a strong tropical storm.[4][7] The storm then moved in a parabolic motion across North Carolina and the Mid-Atlantic before re-emerging into the Atlantic Ocean on August 19. Diane headed east-northeastward until becoming extratropical on August 20.[7]

Despite landfall in North Carolina, impact in the state was minor, limited to moderate rainfall, abnormally high tides, and relatively strong winds. Further north, catastrophic flooding occurred in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and New England. Of the 287 stream gauges in the region, 129 reported record levels after the flooding from Tropical Storm Diane. Many streams reported discharge rates that were more than twice of the previous record. Most of the flooding occurred along small river basins that rapidly rose within hours to flood stage, largely occurring in populated areas;[23] the region in which the floods occurred had about 30 million people,[24] and 813 houses overall were destroyed.[25] The floods severely damaged homes, highways, power lines, and railroads, and affected several summer camps.[23] Overall utility damage was estimated at $79 million. Flooding in mountainous areas caused landslides and destroyed crop fields; agriculture losses was estimated at $7 million. Hundreds of miles of roads and bridges were also destroyed, accounting for $82 million in damage.[25] Overall, Diane caused $754.7 million in damage, of which $600 million was in New England.[4] Overall, there were at least 184 deaths.[26]

Hurricane Edith

[edit]| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 21 – August 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 967 mbar (hPa) |

An easterly tropical wave developed into a tropical depression on August 21 in the tropical Atlantic.[4] Moving towards the west-northwest, the disturbance slowly intensified, reaching tropical storm strength at 1200 UTC on August 23 and as such was named Edith by the Weather Bureau.[7][27] Afterwards, Edith began to curve towards the northwest as it gradually intensified, attaining hurricane strength on August 26, but weakened back to a tropical storm early the next day. The storm re-intensified as it northeastward and accelerated, re-attaining hurricane status early on August 29. Edith became a Category 2 hurricane on August 30 and soon peaked with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 967 mbar (28.6 inHg).[7] The hurricane began to gradually weaken after it passed east of the island, before becoming extratropical on August 31. The extratropical cyclone would later make a clockwise loop before dissipating completely early on September 5. Although Edith remained at sea,[7] it was suspected that the hurricane may have caused the loss of the pleasure yacht Connemara IV, after it separated from its moorings.[28]

Unnamed August tropical storm

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 25 – August 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); ≤1004 mbar (hPa) |

A weak disturbance was first observed near Grand Cayman on August 23.[4] The disturbance moved northeastward into the Gulf of Mexico, where it became a tropical depression late on August 25. Early the next day, the depression intensified into a tropical storm. The tropical storm marginally strengthened further, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) by 0000 UTC on August 27. Nearing the Gulf Coast of the United States, the system curved towards the west.[7] The storm maintained its intensity up until landfall in Louisiana near New Orleans about four hours later.[4] Moving inland, it slowly weakened while crossing the Central United States, degenerating to tropical depression strength by August 28 and dissipating over east-central Texas several hours later.[7]

Strong waves generated by the storm caused tides 4 ft (1.2 m) above average, slightly damaging coastal resorts.[29] Weather offices advised small craft offshore to remain in port due to the strong waves.[30] Rough seas battered the schooner Princess Friday, but the ship was able to ride out the storm.[29] The storm produced squalls further inland, causing heavy rains.[30] Very minor damage occurred as a result of this cyclone.[4]

Hurricane Flora

[edit]| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 2 – September 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 967 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved along the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and passed through Cape Verde between August 30 and August 31. Although the Panair do Brasil headquarters in Recife, Brazil reported a closed circulation on August 30,[4] Tropical Storm Flora did not develop until 0600 UTC on September 2, while located about 400 miles (640 km) of Cape Verde. The storm strengthened at a steady pace for the following 48 hours and reached hurricane status late on September 3. Flora headed on a parabolic track, initially moving west-northwestward and then northwesterly by September 4. It continued to intensify and by September 6, the storm curved northward. Around time, a minimum barometric pressure of 967 mbar (28.6 inHg) was reported, along with a maximum sustained wind speed of 105 mph (169 km/h). Flora weakened slightly to a Category 1 hurricane curving to the northeast late on September 8 and became extratropical at 0600 UTC on September 9, while located about midway between Flores Island in the Azores and Sable Island, Nova Scotia.[7]

Hurricane Gladys

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 3 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression developed in the Bay of Campeche at 1800 UTC on September 3. About 24 hours later, it strengthened into Tropical Storm Gladys. The storm quickly intensified and reached hurricane status on September 5, roughly 24 hours after developing. Around that time, Gladys peaked as a Category 1 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (121 km/h).[7] Later on September 5, an offshoot of Gladys with cyclonic turning formed in the northern Gulf of Mexico and struck Texas on September 6; it may have been a separate tropical cyclone.[4] Initially, Gladys headed north-northwestward, but then re-curved south-southwestward while approaching the Gulf Coast of Mexico. Early on September 6, it made landfall near Tampico, Tamaulipas, as a minimal hurricane. Gladys curved southward while just barely inland and weakened, dissipating near Tuxpan, Veracruz, late on September 6.[7]

Gladys dropped up to 25 inches (640 mm) in Tampico, Tamaulipas. The worst of the flooding from Gladys occurred in Mexico City. Roughly 5,000 residents were isolated and required rescue. Police estimated that 2,300 homes were inundated with 5 to 7 feet (1.5 to 2.1 m) of water. About 30,000 families were impacted by the storm. Two children drowned and five additional people were listed as missing.[31] In Texas, the highest sustained wind speed was 45 mph (72 km/h) in the Corpus Christi–Port O'Connor area, with gusts between 55 and 65 mph (89 and 105 km/h) offshore.[4] Precipitation peaked at 17.02 inches (432 mm) in Flour Bluff, a neighborhood of Corpus Christi.[32] Flooding in the area forced "scores" of people to evacuate their homes.[33] Damage estimates reached $500,000.[4]

Hurricane Ione

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 10 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min); 938 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression early on September 10, while located about midway between Cape Verde and the Lesser Antilles.[4] After six hours, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Ione.[7] Eventually, it turned to the northwest.[4] At 0000 UTC on September 15, Ione reached hurricane intensity, while situated north of the Leeward Islands. Ione continued to deep while moving northwest. The storm reached Category 4 intensity with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 938 mbar (27.7 inHg) early on September 18. Around midday on the following day, it made landfall near Wilmington, North Carolina, as a Category 2 hurricane. Shortly after moving inland over eastern North Carolina, Ione weakened to a tropical storm.[7] Late on September 19, Ione re-emerged into the Atlantic near Norfolk, Virginia.[4] The storm quickly re-strengthened early on September 20, but transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 21.[7]

Strong winds, heavy rainfall, and abnormally high tides lashed some areas along the East Coast of the United States, especially North Carolina.[4] In Cherry Point, sustained winds reached 75 mph (121 km/h), with gusts up to 107 mph (172 km/h).[34] Overall, damage was slightly more than $88 million, mostly to crops and agriculture.[4] Rainfall in the state peaked at 16.63 inches (422 mm) in Maysville.[35] Storm surge in North Carolina peaked at 5.3 feet (1.6 m) in Wrightsville Beach.[36] As a result, several coastal roadways were flooded, including a portion of Highway 94 and Route 264.[37] Seven deaths were reported in North Carolina.[4] The remnants of Ione brought gusty winds to Atlantic Canada, which broken poles, uprooted trees, interrupted telephone service, damaged chimneys and caused power outages, especially in St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador.[38]

Hurricane Hilda

[edit]| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 12 – September 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 952 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave spawned Tropical Storm Hilda north of Puerto Rico early on September 12.[4][7] Hilda quickly intensified while moving westward into a small hurricane by September 13.[7] Although the storm passed just north of Hispaniola on that day, damage is unknown, if any.[4] Later on September 13, Hilda made landfall near the southeastern tip of Cuba on September 13.[7] There, it dropped heavy rainfall and produced gusty winds that destroyed 80% of the coffee crop in Oriente Province.[39] In the eastern Cuban city of Baracoa, Hilda severely damaged the oldest church in the country.[40] Damage totaled $2 million in Cuba,[41] and there were four deaths.[4]

Although Hilda weakened to a tropical storm over southeastern Cuba, the system re-strengthened into a hurricane as it struck Grand Cayman early on September 15. The storm intensified further over the northeastern Caribbean, becoming a Category 3 major hurricane and reaching sustained winds of 120 mph (190 km/h) about 24 hours later. Late on September 16, Hilda struck a sparsely-populated region of the eastern Yucatán Peninsula,[7] causing light damage.[42] Although Hilda quickly weakened to a tropical storm over the Yucatán Peninsula, the cyclone re-strengthened to again reach winds of 120 mph (190 km/h) early on September 19.[7] Before the hurricane moved ashore, there was residual flooding in Tampico from earlier Hurricane Gladys.[43] Hilda struck the city early on September 19 and then rapidly weakened inland, dissipating on September 20.[7] The storm is estimated to have generated gusts up to 150 mph (240 km/h) and dropped heavy rainfall that flooded 90% of Tampico, while its strong winds damaged half of the homes,[42] leaving 15,000 homeless.[44] Throughout Mexico, 11,432 people were directly affected by Hilda.[45] Overall, the storm killed 300 people and caused over $120 million in damages.[4] Additionally, the outer bands of Hilda caused minor flooding in southern Texas, particularly in Raymondville.[46]

Hurricane Janet

[edit]| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 21 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 175 mph (280 km/h) (1-min); 914 mbar (hPa) |

Hurricane Janet was the most powerful tropical cyclone of the season and one of the strongest Atlantic hurricanes on record. The hurricane formed from a tropical wave east of the Lesser Antilles on September 21. Moving toward the west across the Caribbean Sea, Janet fluctuated in intensity, but generally strengthened before reaching its peak intensity as a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale with winds of 175 mph (282 km/h). The intense hurricane made landfall at that intensity near Chetumal, Mexico on September 28. Janet's landfall as a Category 5 hurricane on the Yucatán Peninsula marked the first recorded instance that a storm of such intensity in the Atlantic basin made on a continental mainland, with all previous storms making landfall as Category 5 hurricanes on islands.[47] After weakening to a Category 2 over the Yucatán Peninsula, it moved into the Bay of Campeche and remained mostly unchanged in intensity before making its final landfall near Veracruz on September 29. Janet quickly weakened over Mexico's mountainous terrain before dissipating on September 30.[7]

In its developmental stages near the Lesser Antilles, Janet caused significant damage to the island chain, resulting in 189 deaths and $7.8 million in damages in the Grenadines and Barbados.[48][49] While Janet was in the central Caribbean Sea, a reconnaissance aircraft flew into the storm and was lost, with all eleven crew members believed perished. This was the only such loss which has occurred in association with an Atlantic hurricane.[50] A Category 5 upon landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula, Janet caused severe devastation in areas on Quintana Roo and British Honduras. Only five buildings in Chetumal, Mexico remained intact after the storm. An estimated 500 deaths occurred in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo. At Janet's second landfall near Veracruz, significant river flooding ensued, worsening effects caused by Hurricanes Gladys and Hilda earlier in the month.[4] The floods left thousands of people stranded and killed at least 326 people in the Tampico area. The flood damage would lead to the largest Mexican relief operation ever executed by the United States.[51] At least 1,023 deaths were attributed to Hurricane Janet, as well as $65.8 million in damages.[4][51][52]

Unnamed September tropical storm

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 23 – September 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); ≤1012 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on September 18 and continued west-northwestward. It is possible that the system developed into a tropical depression the next day, although lack of data prevented such classification until September 23, when a nearby ship reported winds of 35 mph (56 km/h). An approaching cold front turned the system to the north on September 24. The structure gradually became better organized, and after turning to the northeast on September 26, the depression intensified into a tropical storm. This was based on a ship report of 45 mph (72 km/h) winds, which was also estimated as the system's peak intensity. On September 27, the system became extratropical and accelerated its forward motion, dissipating within a larger extratropical storm south of Iceland on the next day.[53]

Unnamed October tropical storm

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 10 – October 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); ≤995 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave was reported to have passed through Cape Verde on October 4. The system slowly developed a vertex as it curved in a generally northward direction. By early on October 10, two ships reported that a tropical depression formed almost halfway between the Azores and the Leeward Islands. After six hours, the depression strengthened into a tropical storm. While re-curving to the northeast, the storm attained its maximum sustained winds of 65 mph (105 km/h); the lowest atmospheric pressure recorded in relation to the storm was 1,000 mbar (30 inHg), but the time of measurement is unknown. Although no significant weakening occurred, it eventually merged with an extratropical cyclone on October 14, while still well southwest of the Azores. During its extratropical stage, a ship in the area reported an atmospheric pressure as low as 979 mbar (28.9 inHg).[4]

Hurricane Katie

[edit]| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 14 – October 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); ≤984 mbar (hPa) |

A disturbance in the ITCZ developed into a tropical depression north of Panama on October 14. Early on the following day, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Katie. The system moved generally northeast due to the presence of a strong low pressure area along the East Coast of the United States.[4][54] Later that day, Hurricane Hunters observed a rapidly intensifying hurricane, encountering winds of 110 mph (180 km/h) and a pressure of 984 mbar (29.1 inHg) several hours before the peak intensity. Early on October 17, Katie made landfall in extreme eastern Sud-Est, Haiti, as a strong Category 2 hurricane (although it may have been stronger). About half of homes in the town of Anse-à-Pitres were destroyed.[55] Across the border in Pedernales, Dominican Republic, 68 houses were damaged. Overall losses were at least $200,000 and 7 fatalities were reported.[4]

While crossing the mountainous terrain of Hispaniola, Katie became very disorganized and rapidly weakened to a tropical storm early on October 17, within a few hours after moving inland. Later that day, the storm emerged into the Atlantic Ocean just east of Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic. Katie began accelerating to the northeast on October 18. During that time, the storm re-intensified and briefly approached hurricane intensity, although it failed to strengthen further due to interaction with a cold front. After passing just east of Bermuda on October 19, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. The remnants of Katie were last observed the following day.[4]

Storm names

[edit]The following list of names were used for tropical cyclones that reached at least tropical storm intensity in the North Atlantic in 1955. This was a completely new set of names, thus every name used this season was used for the first time.[56][57]

|

|

|

Retirement

[edit]After the season, the names Connie, Diane, Ione, and Janet were retired from future use within the North Atlantic basin on account of their severity.[58] As of 2024, the 1955 season is one of four seasons to have four storm names retired, along with: 1995, 2004, and 2017; only the 2005 season has had more – with five names retired.[59]

Season effects

[edit]This is a table of all of the storms that formed in the 1955 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their name, duration, peak classification and intensities, areas affected, damage, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 1955 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brenda | July 31 – August 3 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 998 | Louisiana, Florida, Alabama | Minimal | 2 | |||

| Connie | August 3 – 15 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 944 | Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, North Carolina, Mid-Atlantic states, New England, Canada | $86 million | 74 | |||

| Diane | August 7 – 21 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 969 | North Carolina, Mid-Atlantic states, New England | $754.7 million | ≥184 | |||

| Edith | August 21 – 31 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 967 | None | None | None | |||

| Unnamed | August 25 – 28 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1000 | Louisiana, Florida, Alabama | Minimal | None | |||

| Flora | September 2 – 9 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 967 | None | None | None | |||

| Gladys | September 3 – 6 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 996 | Western Mexico, Yucatan Peninsula | $500 thousand | None | |||

| Ione | September 10 – 21 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 938 | Leeward Islands, North Carolina, Virginia, Newfoundland | $88 million | 7 | |||

| Hilda | September 12 – 20 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 952 | Hispaniola, Cuba, Cayman Islands, Yucatán Peninsula, Mainland Mexico | $120 million | 304 | |||

| Janet | September 21 – 30 | Category 5 hurricane | 175 (280) | 914 | Barbados, Windward Islands, British Honduras, Yucatán Peninsula, Mainland Mexico | $65.8 million | 1,023 | |||

| Unnamed | September 23 – 27 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1012 | None | None | None | |||

| Unnamed | October 10 – 14 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 995 | None | None | None | |||

| Katie | October 14 – 19 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 984 | Central America, Dominican Republic, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Bahamas, Dominica | $200 thousand | 7 | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 13 systems | July 31 – October 19 | 175 (280) | 914 | $1.115 billion | 1,601 | |||||

See also

[edit]- 1955 Pacific hurricane season

- 1955 Pacific typhoon season

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 1954–55 1955–56

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 1954–55 1955–56

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 1954–55 1955–56

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "'Miss Hurricane' of '55 To Receive New Name". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. 1955-05-08. p. 54. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ "Navy Hurricane Hunters Get New, Better Planes". St. Petersburg Times. United Press. 1955-06-12. p. 17. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ "Squall Brews Over Hurricanes". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Associated Press. 1955-06-14. p. 18. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Gordon E. Dunn; Walter R. Davis; Paul L. Moore (December 1955). "Hurricanes of 1955" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 83 (12). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: 315–326. Bibcode:1955MWRv...83..315D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1955)083<0315:HO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2011-09-10.

- ^ Dick Bothwell (1960-09-26). "Something's To Be Done About Weather". St. Petersburg Times. p. 9. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ a b "Hurricane Season Opens; New England Joins Circuit". The Robesonian. Associated Press. 1955-06-15. p. 4. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Cold and Warm Episodes by Season (Report). Climate Prediction Center. 2013. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ José A. Colón (1955). On the formation of Hurricane Alice, 1955 (PDF) (Report). U.S. Weather Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2017-08-08.

- ^ Hurricane Research Division (June 2019). "North Atlantic Hurricane Basin (1851-2018): Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ^ David Levinson (2008-08-20). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones (Report). National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2005-12-01. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Slackening Off". The Daytona Beach News-Journal. Associated Press. 1955-08-02. Retrieved 2012-07-24.

- ^ David M. Roth (2007-05-16). Hurricane Connie - August 6-14, 1955 (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ Climatological Data: Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands. Vol. 1. Asheville, North Carolina: United States Weather Bureau. 1957. p. 54. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ a b David Longshore (2008). Encyclopedia of Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Cyclones, New Edition. Facts on File, Inc. p. 105. ISBN 9781438118796. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "Vacationers Caught As Gales Spread Out". The Victoria Advocate. United Press International. 1955-08-13. Retrieved 2013-02-13.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Frederick N. Rasmussen (2004-04-24). "Ship was a tragedy waiting to happen". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 2015-10-15. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "Hurricane Connie Now Medium-Sized". Lewiston Morning-Tribune. Associated Press. 1955-08-15. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "New York Wallows in Heavy Rains". The Times Daily. Associated Press. 1955-08-13. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "Waning Hurricane Connie Poses Threat to Ontario". The Vancouver Sun. Associated Press. 1955-08-13. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ E.V.W. Jones (February 5, 1956). "1955 Broke All Records for Hurricane Damage". Meriden Record. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- ^ 1955-Connie (Report). Environment Canada. 2009-11-09. Archived from the original on 2013-07-03. Retrieved 2021-02-07.

- ^ a b Preliminary Report of Hurricane Diane and Floods in Northeast - August 1955 (PDF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau. 1955-08-25. Retrieved 2013-02-04.

- ^ Floods of August-October 1955: New England to North Carolina. United States Geological Survey. 1960. pp. 15, 27. Retrieved 2013-01-23.

- ^ a b Howard Frederick Matthai (1955). Floods of August 1955 in the Northeastern States (Report). United States Geological Survey. pp. 1–10. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ^ Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas; Jack L. Beven (1997-04-22). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

- ^ "Spotters See Edith Howling in Atlantic". The Victoria Advocate. United Press. 1955-08-24. p. 1. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ Travel Bermuda Incl. Hamilton, Saint George & more. Boston: MobileReference.com. 2010-11-17. ISBN 9781607789475. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- ^ a b "Bermuda in Path Of Raging Edith". The Victoria Advocate. United Press. 1955-08-27. p. 1. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ a b "Edith Shaking Off Lethargy". Ellensburg Daily Record. Associated Press. 1955-08-27. p. 1. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "Floods Hit Mexico City, Peril Texas". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. 1955-09-06. p. 1. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ David M. Roth (2010-01-13). Hurricane Gladys - September 4-8, 1955 (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "Texas Coast Pounded". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Associated Press. 1955-09-07. p. 2.

- ^ Town of Wrightsville Beach Hazard Mitigation Plan (PDF) (Report). Holland Consulting Planners, Inc. March 2010. p. 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-13. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ David M. Roth (2007-06-20). Hurricane Ione - September 18-20, 1955 (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ W. C. Conner; W. H. Kraft and D. Lee Harris (15 July 1957). "April 1957 Monthly Weather Review Storm Surge Methods" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 85 (4): 113–116. Bibcode:1957MWRv...85..113C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.394.7945. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1957)085<0113:emfftm>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ Merlin S. Berry (1995). History of Northeastern North Carolina Storms (Report). NCGenWeb Project. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ 1955-Ione (Report). Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 2013-07-03. Retrieved 2021-02-07.

- ^ "Hurricane Hilda Due To Hit The Yucatan Peninsular Tonight". Lewiston Evening Journal. Associated Press. 1955-09-15. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "Cuba Damaged by Hilda; Ione Brews". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. United Press. 1955-09-16. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ Roger A. Pielke Jr.; Jose Rubiera; Christopher Landsea; Mario L. Fernández; Roberta Klein (August 2003). "Hurricane Vulnerability in Latin America and The Caribbean: Normalized Damage and Loss Potentials" (PDF). National Hazards Review. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: 108. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ^ a b C.E. Rhodes (1955). Tropical Storms of the North Atlantic, September 1955. United States Weather Bureau. pp. 326–328. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "Ione is Bypassing Florida". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Associated Press. 1955-09-18. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "Hilda Leaves 15,000 Homeless, 12 Dead, 350 Hurt in Tampico". The Free Lance-Star. Associated Press. 1955-09-20. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "1955, the year that marked Tampico's History". Así es Tampico. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ^ "Brazos River Settling Down Following Crest at Seymour". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. 1955-09-29. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ National Climatic Data Center. "Category 5 MONSTERS!". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2014-07-10. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ Khalil Goodman (2005-09-21). "Hurricane Janet remembered after 50 years". The Barbados Advocate. Archived from the original on December 24, 2005. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ Chester Layne (September 21, 2005). "Lessons to learn from Janet". The Daily Nation. Archived from the original on December 25, 2005. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

In Barbados, 35 people died, over 8 000 homes were destroyed and 20,000 were left homeless.

- ^ Bill Murray (2009-09-26). "1955: Hurricane Janet and the Hurricane Hunters". The Alabama Weather Blog. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ a b "Tampico Toll 326". The Leader-Post. Mexico City, Mexico. Associated Press. 1955-10-06. p. 1. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ "Thousands Homeless as Hurricane Janet Smashes Barbados". Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. 1955-09-23. p. 6. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ^ Chris Landsea; et al. (May 2015). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (1955) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- ^ Jack W. Roberts (1955-10-17). "Hurricane Buffets Haiti, Moving Away from U.S." Miami Daily News. Retrieved 2021-02-19 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "No Danger as Hurricane Katie Goes Out to Sea". The Telegraph. Associated Press. 1955-10-18. Retrieved 2011-09-10.

- ^ Gary Padgett. "History of the Naming of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Part 1 – The Fabulous Fifties". Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "Gals' Names Still". The Victoria Advocate. United Press International. February 15, 1955. p. 2. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ Kier, Justin (April 13, 2018). "4 deadly 2017 hurricane names retired". Columbia, South Carolina: WACH. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Monthly Weather Review

- The short film Big Picture: Operation Noah is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.