Real-time computer graphics

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

| Three-dimensional (3D) computer graphics |

|---|

|

| Fundamentals |

| Primary uses |

| Related topics |

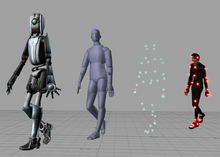

Real-time computer graphics or real-time rendering is the sub-field of computer graphics focused on producing and analyzing images in real time. The term can refer to anything from rendering an application's graphical user interface (GUI) to real-time image analysis, but is most often used in reference to interactive 3D computer graphics, typically using a graphics processing unit (GPU). One example of this concept is a video game that rapidly renders changing 3D environments to produce an illusion of motion.

Computers have been capable of generating 2D images such as simple lines, images and polygons in real time since their invention. However, quickly rendering detailed 3D objects is a daunting task for traditional Von Neumann architecture-based systems. An early workaround to this problem was the use of sprites, 2D images that could imitate 3D graphics.

Different techniques for rendering now exist, such as ray-tracing and rasterization. Using these techniques and advanced hardware, computers can now render images quickly enough to create the illusion of motion while simultaneously accepting user input. This means that the user can respond to rendered images in real time, producing an interactive experience.

Principles of real-time 3D computer graphics

[edit]The goal of computer graphics is to generate computer-generated images, or frames, using certain desired metrics. One such metric is the number of frames generated in a given second. Real-time computer graphics systems differ from traditional (i.e., non-real-time) rendering systems in that non-real-time graphics typically rely on ray tracing. In this process, millions or billions of rays are traced from the camera to the world for detailed rendering—this expensive operation can take hours or days to render a single frame.

Real-time graphics systems must render each image in less than 1/30th of a second. Ray tracing is far too slow for these systems; instead, they employ the technique of z-buffer triangle rasterization. In this technique, every object is decomposed into individual primitives, usually triangles. Each triangle gets positioned, rotated and scaled on the screen, and rasterizer hardware (or a software emulator) generates pixels inside each triangle. These triangles are then decomposed into atomic units called fragments that are suitable for displaying on a display screen. The fragments are drawn on the screen using a color that is computed in several steps. For example, a texture can be used to "paint" a triangle based on a stored image, and then shadow mapping can alter that triangle's colors based on line-of-sight to light sources.

Video game graphics

[edit]Real-time graphics optimizes image quality subject to time and hardware constraints. GPUs and other advances increased the image quality that real-time graphics can produce. GPUs are capable of handling millions of triangles per frame, and modern DirectX/OpenGL class hardware is capable of generating complex effects, such as shadow volumes, motion blurring, and triangle generation, in real-time. The advancement of real-time graphics is evidenced in the progressive improvements between actual gameplay graphics and the pre-rendered cutscenes traditionally found in video games.[1] Cutscenes are typically rendered in real-time—and may be interactive.[2] Although the gap in quality between real-time graphics and traditional off-line graphics is narrowing, offline rendering remains much more accurate.

Advantages

[edit]

Real-time graphics are typically employed when interactivity (e.g., player feedback) is crucial. When real-time graphics are used in films, the director has complete control of what has to be drawn on each frame, which can sometimes involve lengthy decision-making. Teams of people are typically involved in the making of these decisions.

In real-time computer graphics, the user typically operates an input device to influence what is about to be drawn on the display. For example, when the user wants to move a character on the screen, the system updates the character's position before drawing the next frame. Usually, the display's response-time is far slower than the input device—this is justified by the immense difference between the (fast) response time of a human being's motion and the (slow) perspective speed of the human visual system. This difference has other effects too: because input devices must be very fast to keep up with human motion response, advancements in input devices (e.g., the current[when?] Wii remote) typically take much longer to achieve than comparable advancements in display devices.

Another important factor controlling real-time computer graphics is the combination of physics and animation. These techniques largely dictate what is to be drawn on the screen—especially where to draw objects in the scene. These techniques help realistically imitate real world behavior (the temporal dimension, not the spatial dimensions), adding to the computer graphics' degree of realism.

Real-time previewing with graphics software, especially when adjusting lighting effects, can increase work speed.[3] Some parameter adjustments in fractal generating software may be made while viewing changes to the image in real time.

Rendering pipeline

[edit]The graphics rendering pipeline ("rendering pipeline" or simply "pipeline") is the foundation of real-time graphics.[4] Its main function is to render a two-dimensional image in relation to a virtual camera, three-dimensional objects (an object that has width, length, and depth), light sources, lighting models, textures and more.

Architecture

[edit]The architecture of the real-time rendering pipeline can be divided into conceptual stages: application, geometry and rasterization.

Application stage

[edit]The application stage is responsible for generating "scenes", or 3D settings that are drawn to a 2D display. This stage is implemented in software that developers optimize for performance. This stage may perform processing such as collision detection, speed-up techniques, animation and force feedback, in addition to handling user input.

Collision detection is an example of an operation that would be performed in the application stage. Collision detection uses algorithms to detect and respond to collisions between (virtual) objects. For example, the application may calculate new positions for the colliding objects and provide feedback via a force feedback device such as a vibrating game controller.

The application stage also prepares graphics data for the next stage. This includes texture animation, animation of 3D models, animation via transforms, and geometry morphing. Finally, it produces primitives (points, lines, and triangles) based on scene information and feeds those primitives into the geometry stage of the pipeline.

Geometry stage

[edit]The geometry stage manipulates polygons and vertices to compute what to draw, how to draw it and where to draw it. Usually, these operations are performed by specialized hardware or GPUs.[5] Variations across graphics hardware mean that the "geometry stage" may actually be implemented as several consecutive stages.

Model and view transformation

[edit]Before the final model is shown on the output device, the model is transformed onto multiple spaces or coordinate systems. Transformations move and manipulate objects by altering their vertices. Transformation is the general term for the four specific ways that manipulate the shape or position of a point, line or shape.

Lighting

[edit]In order to give the model a more realistic appearance, one or more light sources are usually established during transformation. However, this stage cannot be reached without first transforming the 3D scene into view space. In view space, the observer (camera) is typically placed at the origin. If using a right-handed coordinate system (which is considered standard), the observer looks in the direction of the negative z-axis with the y-axis pointing upwards and the x-axis pointing to the right.

Projection

[edit]Projection is a transformation used to represent a 3D model in a 2D space. The two main types of projection are orthographic projection (also called parallel) and perspective projection. The main characteristic of an orthographic projection is that parallel lines remain parallel after the transformation. Perspective projection utilizes the concept that if the distance between the observer and model increases, the model appears smaller than before. Essentially, perspective projection mimics human sight.

Clipping

[edit]Clipping is the process of removing primitives that are outside of the view box in order to facilitate the rasterizer stage. Once those primitives are removed, the primitives that remain will be drawn into new triangles that reach the next stage.

Screen mapping

[edit]The purpose of screen mapping is to find out the coordinates of the primitives during the clipping stage.

Rasterizer stage

[edit]The rasterizer stage applies color and turns the graphic elements into pixels or picture elements.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Spraul, V. Anton (2013). How Software Works: The Magic Behind Encryption, CGI, Search Engines and Other Everyday Technologies. No Starch Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-1593276669. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ Wolf, Mark J. P. (2008). The Video Game Explosion: A History from PONG to Playstation and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. p. 86. ISBN 9780313338687. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ Birn, Jeremy (2013). Digital Lighting and Rendering: Edition 3. New Riders. p. 442. ISBN 9780133439175. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ Akenine-Möller, Tomas; Eric Haines; Naty Hoffman (2008). Real-Time Rendering, Third Edition: Edition 3. CRC Press. p. 11. ISBN 9781439865293. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Boresko, Alexey; Evgeniy Shikin (2013). Computer Graphics: From Pixels to Programmable Graphics Hardware. CRC Press. p. 5. ISBN 9781482215571. Retrieved 22 September 2017.[dead link]

Bibliography

[edit]- Möller, Tomas; Haines, Eric (1999). Real-Time Rendering (1st ed.). Natick, MA: A K Peters, Ltd.

- Salvator, Dave (21 June 2001). "3D Pipeline". Extremetech.com. Extreme Tech. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 2 Feb 2007.

- Malhotra, Priya (July 2002). Issues involved in Real-Time Rendering of Virtual Environments (Master's). Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Tech. pp. 20–31. hdl:10919/35382. Retrieved 31 January 2007.

- Haines, Eric (1 February 2007). "Real-Time Rendering Resources". Retrieved 12 Feb 2007.

External links

[edit]- RTR Portal – a trimmed-down "best of" set of links to resources