Prodrazverstka

Prodrazverstka, also transliterated prodrazvyorstka (Russian: продразвёрстка, IPA: [prədrɐˈzvʲɵrstkə], short for продовольственная развёрстка, lit. 'food apportionment'), alternatively referred to in English as grain requisitioning,[1][2][3][4][5] was a policy and campaign of confiscation of grain and other agricultural products from peasants at nominal fixed prices according to specified quotas (the noun razverstka, Russian: развёрстка, and the verb razverstat, refer to the partition of the requested total amount as obligations from the suppliers). This strategy often led to the deaths of many country-dwelling people, such as its involvement with the Holodomor[citation needed] and Kazakh famines of 1919–1922 and 1930–1933.[citation needed]

The term is commonly associated with war communism during the Russian Civil War when it was introduced by the Bolshevik government. However, Bolsheviks borrowed the idea from the grain razverstka introduced in the Russian Empire in 1916 during World War I.

World War I grain razverstka

[edit]1916 saw a food crisis in the Russian Empire. While the harvest was good in Lower Volga Region and Western Siberia, its transportation by railroads collapsed. Additionally, the food market was in disarray as fixed prices for government purchases were unattractive. A decree of November 29, 1916 signed by Aleksandr Rittich of the Ministry of Agriculture introduced razverstka as the collection of grain for defense purposes. The Russian Provisional Government established after the February Revolution of 1917 could not propose any incentives for peasants, and their state monopoly on grain sales failed to achieve its goal.[6][7]

Soviet prodrazverstka

[edit]In 1918 the center of Soviet Russia found itself cut off from the most important agricultural regions of the country - at this stage of the Russian Civil War the White movement controlled many of the traditional food-producing areas. Reserves of grain ran low, causing hunger among the urban population, from which the Bolshevik government received its strongest support.[citation needed] In order to satisfy minimal food needs, the Soviet government introduced strict control over the food surpluses of prosperous rural households.[citation needed] Since many peasants were extremely unhappy with this policy and tried to resist it, they were branded as "saboteurs" of the bread monopoly of the state and advocates of free "predatory", "speculative" trade.[citation needed] Vladimir Lenin believed that prodrazvyorstka was the only possible way - in the circumstances - to procure sufficient amounts of grain and other agricultural products for the population of the cities during the civil war.[8][need quotation to verify][9]

Before prodrazverstka, Lenin's May 9, 1918 decree ("О продовольственной диктатуре") introduced the concept of "produce dictatorship". This and other subsequent decrees ordered the forced collection of foodstuffs, without any limitations, and used the Red Army to accomplish this.

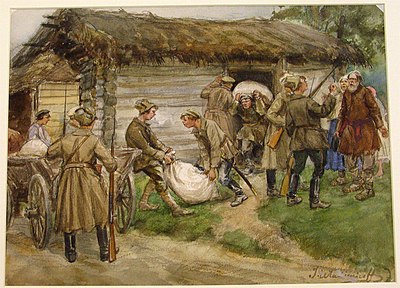

A decree of the Sovnarkom introduced prodrazvyorstka throughout Soviet Russia on January 11, 1919. The authorities extended the system to Ukraine and Belarus in 1919, and to Turkestan and Siberia in 1920. In accordance with the decree of the People's Commissariat for Provisions on the procedures of prodrazvyorstka (January 13, 1919), the number of different kinds of products designated for collection by the state was calculated on the basis of the data on each guberniia's areas under crops, crop capacity and the reserves of past years. Within each guberniia, the collection plan was broken down between uezds, volosts, villages, and then separate peasant households. The collection procedures were performed by the agencies of the People's Commissariat for Provisions and prodotriads (singular: продовольственный отряд, food brigades) with the help of kombeds (комитет бедноты, committees of the poor) and of local Soviets.

Initially, prodrazverstka covered the collection of grain and fodder. During the procurement campaign of 1919–20, prodrazverstka also included potatoes and meat. By the end of 1920, it included almost every kind of agricultural product. According to Soviet statistics, the authorities collected 107.9 million poods (1.77 million metric tons) of grain and fodder in 1918–19, 212.5 million poods (3.48 million metric tons) in 1919–20, and 367 million poods (6.01 million metric tons) in 1920–21.[citation needed]

Prodrazverstka allowed the Soviet government to solve the important problem of supplying the Red Army and the urban population, and of providing raw materials for various industries. Prodrazverstka left its mark on commodity-money relations, since the authorities had prohibited selling of bread and grain. It also influenced relations between the city and the village and became one of the most important elements of the system of war communism.

As the Russian Civil War approached its end in the 1920s, prodrazverstka lost its actuality, but it had done much damage to the agricultural sector and had caused growing discontent among peasants.[citation needed] As the government switched to the NEP (New Economic Policy), a decree of the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in March 1921 replaced prodrazverstka with prodnalog (food tax).

See also

[edit]- Lenin's Hanging Order

- Soviet grain procurement crisis of 1928

- Ural-Siberian method of grain procurement

Literature

[edit]- Silvana Malle (2002) , Prodrazverstka, The Economic Organization of War Communism 1918–1921. Cambridge University Press. 568 p. (Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies, Vol. 47). ISBN 978-0521527033

References

[edit]- ^ Peeling, Siobhan (2014). "War Communism | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)". encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net. Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

Practices of forcible grain requisitioning and monopolisation of supply distribution were intended to ensure minimum levels of food reached the Red Army and the starving cities.

- ^ Llewelyn, Jennifer; et al. (4 December 2012). "The New Economic Policy (NEP)". Russian Revolution. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

The NEP ended the policy of grain requisitioning and introduced elements of capitalism and free trade into the Soviet economy." "The formal decree that introduced the NEP was called "On the replacement of prodrazvyorstka [grain requisitioning] with prodnalog [a fixed tax]". Under war communism and prodrazvyorstka, the amount of grain requisitioned was decided on-the-spot by unit commanders.

- ^ "Prodrazverstka | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ "Instructions for Requisitioning Grain". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. 24 August 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ alphahis (26 July 2019). "Bolshevik decree on food procurement (1918)". Russian Revolution. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Dronin, Nikolai; Bellinger, Edward (2005), Climate Dependence and Food Problems in Russia, 1900–1990: The Interaction of Climate and Agricultural Policy and Their Effect on Food Problems, Central European University Press, pp. 65, 66, ISBN 963-7326-10-3.

- ^ "г. session of State Duma", Free Duma (in Russian), RU: Kodeks, 14 February 1917[permanent dead link], where Rittich reports on the introduction and results of the grain razvyorstka.

- ^ Lenin, VI (1965), Collected Works, vol. 32, Moscow: Progress Publishers, p. 187.

- ^

Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich (1977). Collected Works. Vol. 32. Moscow: Progress Publishers. p. 289. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

[...] we could hold out — in a besieged fortress — only through the surplus-grain appropriation system [...]

- This article includes content derived from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 1969–1978, which is partially in the public domain.