Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 27 October, c. 1500[1]: 135 |

| Died | 21 May 1542 (aged about 41) Guachoya on the bank of the Mississippi River |

| Occupation(s) | Explorer and conquistador |

| Spouse | Isabel de Bobadilla |

| Signature | |

| |

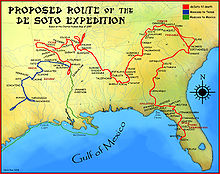

Hernando de Soto (/də ˈsoʊtoʊ/;[2] Spanish: [eɾˈnando ðe ˈsoto]; c. 1497 – 21 May 1542) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru, but is best known for leading the first European expedition deep into the territory of the modern-day United States (through Florida, Georgia, Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina, Mississippi, and most likely Arkansas).[3] [4] He is the first European documented as having crossed the Mississippi River.[5]

De Soto's North American expedition was a vast undertaking. It ranged throughout what is now the southeastern United States, searching both for gold, which had been reported by various Native American tribes and earlier coastal explorers, and for a passage to China or the Pacific coast. De Soto died in 1542 on the banks of the Mississippi River;[6] sources disagree on the exact location, whether it was what is now Lake Village, Arkansas, or Ferriday, Louisiana.

Early life

[edit]Hernando de Soto was born around the late 1490s or early 1500s in Extremadura, Spain, to parents who were both hidalgos, nobility of modest means. The region was poor and many people struggled to survive; young people looked for ways to seek their fortune elsewhere. He was born in the current province of Badajoz.[1] Three towns—Badajoz, Barcarrota and Jerez de los Caballeros—each claim to be his birthplace. Historian Ursula Lamb writes that the Barcarrota claim can be traced to Inca Garcilaso de la Vega and is probably incorrect, having been written down 45 years after De Soto's death. According to Lamb, his birthplace is most likely Jerez de los Caballeros.[7] Although he spent time as a child at each place, De Soto stipulated in his will that his body be interred at Jerez de los Caballeros, where other members of his family were buried.[8]

A few years before his birth, the Kingdoms of Castille and Aragon conquered the last Islamic kingdom of the Iberian Peninsula. Spain and Portugal were filled with young men seeking a chance for military fame after the defeat of the Moors. With Christopher Columbus's discovery of new lands (which he thought to be East Asia) across the ocean to the west, young men were attracted to rumors of adventure, glory and wealth.

In the New World

[edit]De Soto sailed to the New World with Pedro Arias Dávila, appointed as the first Governor of Panama. In 1520 he participated in Gaspar de Espinosa's expedition to Veragua, and in 1524, he participated in the conquest of Nicaragua under Francisco Hernández de Córdoba. There he acquired an encomienda and a public office in León, Nicaragua.[1]: 135 Brave leadership, unwavering loyalty, and ruthless schemes for the extortion of native villages for their captured chiefs became de Soto's hallmarks during the conquest of Central America. He gained fame as an excellent horseman, fighter, and tactician. During that time, de Soto was influenced by the achievements of Iberian explorers: Juan Ponce de León, the first European to reach Florida; Vasco Núñez de Balboa, the first European to reach the Pacific Ocean coast of the Americas (he called it the "South Sea" on the south coast of Panama); and Ferdinand Magellan, who first sailed that ocean to East Asia. In 1530, de Soto became a regidor of León, Nicaragua. He led an expedition up the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula searching for a passage between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean to enable trade with the Orient, the richest market in the world. Failing that, and without means to explore further, de Soto, upon Pedro Arias Dávila's death, left his estates in Nicaragua. Bringing his own men on ships which he hired, de Soto joined Francisco Pizarro at his first base of Tumbes shortly before departure for the interior of present-day Peru.[9]: 143

Pizarro quickly made de Soto one of his captains.[1]: 171

Conquest of Peru

[edit]When Pizarro and his men first encountered the army of Inca Atahualpa at Cajamarca, Pizarro sent de Soto with fifteen men to invite Atahualpa to a meeting. When Pizarro's men attacked Atahualpa and his guard the next day (the Battle of Cajamarca), de Soto led one of the three groups of mounted soldiers. The Spanish captured Atahualpa. De Soto was sent to the camp of the Inca army, where he and his men plundered Atahualpa's tents.[10]

During 1533, the Spanish held Atahualpa captive in Cajamarca for months while his subjects paid for his ransom by filling a room with gold and silver objects. During this captivity, de Soto became friendly with Atahualpa and taught him to play chess. By the time the ransom had been completed, the Spanish became alarmed by rumors of an Inca army advancing on Cajamarca. Pizarro sent de Soto with 200 soldiers to scout for the rumored army.[11]

While de Soto was gone, the Spanish in Cajamarca decided to kill Atahualpa to prevent his rescue. De Soto returned to report that he found no signs of an army in the area. After executing Atahualpa, Pizarro and his men headed to Cuzco, the capital of the Incan Empire. As the Spanish force approached Cuzco, Pizarro sent his brother Hernando and de Soto ahead with 40 men. The advance guard fought a pitched battle with Inca troops in front of the city, but the battle had ended before Pizarro arrived with the rest of the Spanish party. The Inca army withdrew during the night. The Spanish plundered Cuzco, where they found much gold and silver. As a mounted soldier, de Soto received a share of the plunder, which made him very wealthy. It represented riches from Atahualpa's camp, his ransom, and the plunder from Cuzco.[12]

On the road to Cuzco, Manco Inca Yupanqui, a brother of Atahualpa, had joined Pizarro. Manco had been hiding from Atahualpa in fear of his life, and was happy to gain Pizarro's protection. Pizarro arranged for Manco to be installed as the Inca leader. De Soto joined Manco in a campaign to eliminate the Inca armies under Quizquiz, a general who had been loyal to Atahualpa.[13]: 66–67, 70–73

By 1534, de Soto was serving as lieutenant governor of Cuzco while Pizarro was building his new capital on the coast; it later became known as Lima. In 1535 King Charles awarded Diego de Almagro, Francisco Pizarro's partner, the governorship of the southern portion of the Inca Empire. When de Almagro made plans to explore and conquer the southern part of the Inca empire (now Chile), de Soto applied to be his second-in-command, but de Almagro turned him down. De Soto packed up his treasure and returned to Spain.[1]: 367, 370–372, 375, 380–381, 396

Return to Spain

[edit]De Soto returned to Spain in 1536,[1]: 135 with wealth gathered from plunder in the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. He was admitted into the prestigious Order of Santiago and "granted the right to conquer Florida".[1]: 135 His share was awarded to him by the King of Spain, and he received 724 marks of gold, and 17,740 pesos.[14] He married Isabel de Bobadilla, daughter of Pedrarias Dávila and a relative of a confidante of Queen Isabella.

De Soto petitioned King Charles to lead the government of Guatemala, with "permission to create discovery in the South Sea." He was granted the governorship of Cuba instead. De Soto was expected to colonize the North American continent for Spain within 4 years, for which his family would be given a sizable piece of land.

Fascinated by the stories of Cabeza de Vaca, who had survived years in North America after becoming a castaway and had just returned to Spain, de Soto selected 620 Spanish and Portuguese volunteers, including some of mixed-race African descent known as Atlantic Creoles, to accompany him to govern Cuba and colonize North America. Averaging 24 years of age, the men embarked from Havana on seven of the King's ships and two caravels of de Soto's. With tons of heavy armor and equipment, they also carried more than 500 head of livestock, including 237 horses and 200 pigs, for their planned four-year continental expedition.

De Soto wrote a new will upon arriving in what is now the Tampa Bay area of Florida. On 10 May 1539, he wrote in his will:

That a chapel be erected within the Church of San Miguel in Jerez de Los Caballeros, Spain, where De Soto grew up, at a cost of 2,000 ducats, with an altarpiece featuring the Virgin Mary, Our Lady of the Conception, that his tomb be covered in a fine black broadcloth topped by a red cross of the Order of the Knights of Santiago, and on special occasions a pall of black velvet with the De Soto coat of arms be placed on the altar; that a chaplain be hired at the salary of 12,000 maravedis to perform five masses every week for the souls of De Soto, his parents, and wife; that thirty masses be said for him the day his body was interred, and twenty for our Lady of the Conception, ten for the Holy Ghost, sixty for souls in purgatory and masses for many others as well; that 150000 maravedis be given annually to his wife Isabel for her needs and an equal amount used yearly to marry off three orphan damsels...the poorest that can be found," to assist his wife and also serve to burnish the memory of De Soto as a man of charity and substance.[15]

De Soto's exploration of North America

[edit]

Historiography

[edit]Historians have worked to trace the route of de Soto's expedition in North America, a controversial process over the years.[17] Local politicians vied to have their localities associated with the expedition. The most widely used version of "De Soto's Trail" comes from a study commissioned by the United States Congress. A committee chaired by the anthropologist John R. Swanton published The Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission in 1939. Among other locations, Manatee County, Florida, claims an approximate landing site for de Soto and has a national memorial recognizing that event.[18] In the early 21st century, the first part of the expedition's course, up to de Soto's battle at Mabila (a small fortress town in present-day central Alabama[19]), is disputed only in minor details. His route beyond Mabila is contested. Swanton reported the de Soto trail ran from there through Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas.

Historians have more recently considered archeological reconstructions and the oral history of the various Native American peoples who recount the expedition.[citation needed] Most historical places have been overbuilt and much evidence has been lost.[citation needed] More than 450 years have passed between the events and current history tellers, but some oral histories have been found to be accurate about historic events that have been otherwise documented.[citation needed]

The Governor Martin Site at the former Apalachee village of Anhaica, located about a mile east of the present Florida capital in Tallahassee, has been documented as definitively associated with de Soto's expedition. The Governor Martin Site was discovered by archaeologist B. Calvin Jones in March 1987. It has been preserved as the DeSoto Site Historic State Park.

The Hutto/Martin Site, 8MR3447, in southeastern Marion County, Florida, on the Ocklawaha River, is the most likely site of the principal town of Acuera referred to in the accounts of the entrada, as well as the site of the seventeenth-century mission of Santa Lucia de Acuera.[20][21]

As of 2016, the Richardson/UF Village site (8AL100) in Alachua County, west of Orange Lake, appears to have been accepted by archaeologists as the site of the town of Potano visited by the de Soto expedition. The 17th-century mission of San Buenaventura de Potano is believed to have been founded here.[22]

Many archaeologists believe the Parkin Archeological State Park in northeast Arkansas was the main town for the indigenous province of Casqui, which de Soto had recorded. They base this on similarities between descriptions from the journals of the de Soto expedition and artifacts of European origin discovered at the site in the 1960s.[23][24]

Theories of de Soto's route are based on the accounts of four chroniclers of the expedition.

- The first account of the expedition to be published was by the Gentleman of Elvas, an otherwise unidentified Portuguese knight who was a member of the expedition. His chronicle was first published in 1557. An English translation by Richard Hakluyt was published in 1609.[25]

- Luys Hernández de Biedma, the King's factor (the agent responsible for the royal property) with the expedition, wrote a report which still exists. The report was filed in the royal archives in Spain in 1544. The manuscript was translated into English by Buckingham Smith and published in 1851.[26]

- De Soto's secretary, Rodrigo Ranjel, kept a diary, which has been lost. It was apparently used by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés in writing his La historia general y natural de las Indias. Oviedo died in 1557. The part of his work containing Ranjel's diary was not published until 1851. An English translation of Ranjel's report was first published in 1904.

- The fourth chronicle is by Garcilaso de la Vega, known as El Inca (the Inca). Garcilaso de la Vega did not participate in the expedition. He wrote his account, La Florida, known in English as The Florida of the Inca, decades after the expedition, based on interviews with some survivors of the expedition. The book was first published in 1605. Historians have identified problems with using La Florida as a historical account. Milanich and Hudson warn against relying on Garcilaso, noting serious problems with the sequence and location of towns and events in his narrative. They say, "some historians regard Garcilaso's La Florida to be more a work of literature than a work of history."[27] Lankford characterizes Garcilaso's La Florida as a collection of "legend narratives", derived from a much-retold oral tradition of the survivors of the expedition.[28]

Milanich and Hudson warn that older translations of the chronicles are often "relatively free translations in which the translators took considerable liberty with the Spanish and Portuguese text."[29]

The chronicles describe de Soto's trail in relation to Havana, from which they sailed; the Gulf of Mexico, which they skirted while traveling inland then turned back to later; the Atlantic Ocean, which they approached during their second year; high mountains, which they traversed immediately thereafter; and dozens of other geographic features along their way, such as large rivers and swamps, at recorded intervals. Given that the natural geography has not changed much since de Soto's time, scholars have analyzed those journals with modern topographic intelligence, to develop a more precise account of the De Soto Trail.[16][30]

1539: Florida

[edit]

The Spanish caption reads:

"HERNANDO DE SOTO: Extremaduran, one of the discoverers and conquerors of Peru: he travelled across all of Florida and defeated its previously invincible natives, he died on his expedition in the year 1542 at the age of 42".

In May 1539, de Soto landed nine ships with over 620 men and 220 horses in an area generally identified as south Tampa Bay. Historian Robert S. Weddle has suggested that he landed at either Charlotte Harbor or San Carlos Bay.[31] He named the land as Espíritu Santo after the Holy Spirit. The ships carried priests, craftsmen, engineers, farmers, and merchants; some with their families, some from Cuba, most from Europe and Africa. Few of the men had traveled before outside of Spain, or even away from their home villages.

Near de Soto's port, the party found Juan Ortiz, a Spaniard living with the Mocoso people. Ortiz had been captured by the Uzita while searching for the lost Narváez expedition; he later escaped to Mocoso. Ortiz had learned the Timucua language and served as an interpreter to de Soto as he traversed the Timucuan-speaking areas on his way to Apalachee.[32]

Ortiz developed a method for guiding the expedition and communicating with the various tribes, who spoke many dialects and languages. He recruited guides from each tribe along the route. A chain of communication was established whereby a guide who had lived in close proximity to another tribal area was able to pass his information and language on to a guide from a neighboring area. Because Ortiz refused to dress as a hidalgo Spaniard, other officers questioned his motives. De Soto remained loyal to Ortiz, allowing him the freedom to dress and live among his native friends. Another important guide was the seventeen-year-old boy Perico, or Pedro, from what is now Georgia. He spoke several of the local tribes' languages and could communicate with Ortiz. Perico was taken as a guide in 1540. The Spanish had also captured other Indians, whom they used as slave labor.[clarification needed] Perico was treated better due to his value to the Spaniards.

The expedition traveled north, exploring Florida's West Coast, and encountering native ambushes and conflicts along the way. Hernando de Soto's army seized the food stored in the villages, captured women to be used as slaves for the soldiers' sexual gratification, and forced men and boys to serve as guides and bearers. The army fought two battles with Timucua groups, resulting in heavy Timucua casualties. After defeating the resisting Timucuan warriors, Hernando de Soto had 200 executed, in what was to be called the Napituca Massacre, the first large-scale massacre by Europeans in the current United States.[33] One of Soto’s most important battles with the natives, along his conquest of Florida, was a 1539 battle with Chief Vitachuco. Unlike other native chiefs who entered into peace with the Spanish, Vitachuco did not trust them and had secretly plotted to kill Soto and his army, but he was betrayed by interpreters who told Soto the plan. So, Soto struck first and, in the process, killed thousands of natives. Those that survived were surrounded and cornered by woods and water. Thousands were killed during the 3 hours battle and 900 survivors took refuge in the pond, specifically Two-mile Pond in Melrose, where they continued to fight, while swimming.[34][35] Most eventually surrendered, but after 30 hours in the water, 7 men remained and had to be dragged out of the water by the Spanish. De Soto's first winter encampment was at Anhaica, the capital of the Apalachee people. It is one of the few places on the route where archaeologists have found physical traces of the expedition. The chroniclers described this settlement as being near the "Bay of Horses". The bay was named for events of the 1527 Narváez expedition, the members of which, dying of starvation, killed and ate their horses while building boats for escape by the Gulf of Mexico.

1540: The Southeast

[edit]From their winter location in the western panhandle of Florida, having heard of gold being mined "toward the sun's rising", the expedition turned northeast through what is now the modern state of Georgia.[36][37] Based on archaeological finds made in 2009 at a remote, privately owned site near the Ocmulgee River, researchers believe that de Soto's expedition stopped in Telfair County. Artifacts found here include nine glass trade beads, some of which bear a chevron pattern made in Venice for a limited period of time and believed to be indicative of the de Soto expedition. Six metal objects were also found, including a silver pendant and some iron tools. The rarest items were found within what researchers believe was a large council house of the indigenous people whom de Soto was visiting.[38][39]

The expedition continued to present-day South Carolina. There the expedition recorded being received by a female chief (The Lady of Cofitachequi), who gave her tribe's pearls, food and other goods to the Spanish soldiers. The expedition found no gold, however, other than pieces from an earlier coastal expedition (presumably that of Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón.)

De Soto headed north into the Appalachian Mountains of present-day western North Carolina, where he spent a month resting the horses while his men searched for gold. De Soto next entered eastern Tennessee. At this point, de Soto either continued along the Tennessee River to enter Alabama from the north (according to John R. Swanton), or turned south and entered northern Georgia (according to Charles M. Hudson). Swanton's final report, published by the Smithsonian, remains an important resource[40] but Hudson's reconstruction of the route was conducted 40 years later and benefited from considerable advances in archaeological methods.[41]

De Soto's expedition spent another month in the Coosa chiefdom a vassal to Tuskaloosa, who was the paramount chief,[citation needed] believed to have been connected to the large and complex Mississippian culture, which extended throughout the Mississippi Valley and its tributaries. De Soto turned south toward the Gulf of Mexico to meet two ships bearing fresh supplies from Havana. De Soto demanded women and servants, and when Tuskaloosa refused, the European explorers took him hostage.[42] The expedition began making plans to leave the next day, and Tuskaloosa gave in to de Soto's demands, providing bearers for the Spaniards. He informed de Soto that they would have to go to his town of Mabila (or Mauvila), a fortified city in southern Alabama,[43] to receive the women. De Soto gave the chief a pair of boots and a red cloak to reward him for his cooperation.[44] The Mobilian tribe, under chief Tuskaloosa, ambushed de Soto's army.[43] Other sources suggest de Soto's men were attacked after attempting to force their way into a cabin occupied by Tuskaloosa.[45] The Spaniards fought their way out, and retaliated by burning the town to the ground. During the nine-hour encounter, about 200 Spaniards died, and 150 more were badly wounded, according to the chronicler Elvas.[46] Twenty more died during the next few weeks. They killed an estimated 2,000–6,000 Native Americans at Mabila, making the battle one of the bloodiest in recorded North American history.[47]

The Spaniards won a Pyrrhic victory, as they had lost most of their possessions and nearly one-quarter of their horses. The Spaniards were wounded and sickened, surrounded by enemies and without equipment in an unknown territory.[45] Fearing that word of this would reach Spain if his men reached the ships at Mobile Bay, de Soto led them away from the Gulf Coast. He moved into inland Mississippi, most likely near present-day Tupelo, where they spent the winter.

1541: Westward

[edit]

In the spring of 1541, de Soto demanded 200 men as porters from the Chickasaw.[48] They refused his demand and attacked the Spanish camp during the night.

On 8 May 1541, de Soto's troops reached the Mississippi River.[5]

De Soto had little interest in the river, which in his view was an obstacle to his mission. There has been considerable research into the exact location where de Soto crossed the Mississippi River. A commission appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935 determined that Sunflower Landing, Mississippi, was the "most likely" crossing place. De Soto possibly traveled down Charley's Trace, which had been used as a trail through the swamps of the Mississippi Delta, to reach the Mississippi River.[49] De Soto and his men spent a month building flatboats, and crossed the river at night to avoid the Native Americans who were patrolling the river. De Soto had hostile relations with the native people in this area.[50][51]

In the late 20th century, research suggests other locations may have been the site of de Soto's crossing, including three locations in Mississippi: Commerce, Friars Point, and Walls, as well as Memphis, Tennessee.[52] Once across the river, the expedition continued traveling westward through modern-day Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. They wintered in Autiamique, on the Arkansas River.[53]

After a harsh winter, the Spanish expedition decamped and moved on more erratically. Their interpreter Juan Ortiz had died, making it more difficult for them to get directions and food sources, and generally to communicate with the Natives. The expedition went as far inland as the Caddo River, where they clashed with a Native American tribe called the Tula in October 1541.[54] The Spaniards characterized them as the most skilled and dangerous warriors they had encountered.[55] This may have happened in the area of present-day Caddo Gap, Arkansas (a monument to the de Soto expedition was erected in that community). Eventually, the Spaniards returned to the Mississippi River.

Death

[edit]

De Soto died of a fever on 21 May 1542, in the native village of Guachoya. Historical sources disagree as to whether de Soto died near present-day Lake Village, Arkansas[56] McArthur, Arkansas, or Ferriday, Louisiana.[57] Louisiana erected a historical marker at the estimated site[58] on the western bank of the Mississippi River.[59]

Before his death, de Soto chose Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, his former maestro de campo (or field commander), to assume command of the expedition.[60] At the time of death, de Soto owned four Indian slaves, three horses, and 700 hogs.[61]

De Soto had deceived the local natives into believing that he was a deity, specifically an "immortal Son of the Sun,"[56] to gain their submission without conflict. Some of the natives had already become skeptical of de Soto's deity claims, so his men were anxious to conceal his death. The actual site of his burial is not known. According to one source, de Soto's men hid his corpse in blankets weighted with sand and sank it in the middle of the Mississippi River during the night.[57]

Return of the expedition to Mexico City

[edit]De Soto's expedition had explored La Florida for three years without finding the expected treasures or a hospitable site for colonization. They had lost nearly half their men, and most of the horses. By this time, the soldiers were wearing animal skins for clothing. Many were injured and in poor health. The leaders came to a consensus (although not total) to end the expedition and try to find a way home, either down the Mississippi River, or overland across Texas to the Spanish colony of Mexico City.

They decided that building boats would be too difficult and time-consuming and that navigating the Gulf of Mexico was too risky, so they headed overland to the southwest. Eventually, they reached a region in present-day Texas that was dry. The native populations were made up mostly of subsistence hunter-gatherers. The soldiers found no villages to raid for food, and the army was still too large to live off the land. They were forced to backtrack to the more developed agricultural regions along the Mississippi, where they began building seven bergantines, or pinnaces.[60] They melted down all the iron, including horse tackle and slave shackles, to make nails for the boats. They survived through the winter, and the spring floods delayed them another two months. By July they set off on their makeshift boats down the Mississippi for the coast.

Taking about two weeks to make the journey, the expedition encountered hostile fleets of war canoes along the whole course. The first was led by the powerful paramount chief Quigualtam, whose fleet followed the boats, shooting arrows at the soldiers for days as they drifted through their territory. The Spanish had no effective offensive weapons on the water, as their crossbows had long since ceased working. They relied on armor and sleeping mats to block the arrows. About 11 Spaniards were killed along this stretch and many more wounded.[citation needed]

On reaching the mouth of the Mississippi, they stayed close to the Gulf shore heading south and west. After about 50 days, they made it to the Pánuco River and the Spanish frontier town of Pánuco. There they rested for about a month. During this time many of the Spaniards, having safely returned and reflecting on their accomplishments, decided they had left La Florida too soon. There were some fights within the company, leading to some deaths. But, after they reached Mexico City and the Viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza offered to lead another expedition to La Florida, few of the survivors volunteered. Of the recorded 700 participants at the start, between 300 and 350 survived (311 is a commonly accepted figure). Most of the men stayed in the New World, settling in Mexico, Peru, Cuba, and other Spanish colonies.[citation needed]

Effects of expedition in North America

[edit]The Spanish believed that de Soto's excursion to Florida was a failure. They acquired neither gold nor prosperity and founded no colonies. But the expedition had several major consequences.

It contributed to the process of the Columbian Exchange. For instance, some of the swine brought by de Soto escaped and became the ancestors of feral razorback pigs in the southeastern United States.[62][63][64][65][66]

De Soto was instrumental in contributing to the development of a hostile relationship between many Native American tribes and Europeans. When his expedition encountered hostile natives in the new lands, more often than not it was his men who instigated the clashes.[67]

More devastating than the battles were the diseases which may have been carried by the members of the expedition. Because the indigenous people lacked the immunity which the Europeans had acquired through generations of exposure to these Eurasian diseases, the Native Americans may have suffered epidemics of illness after exposure to such diseases as measles, smallpox, and chicken pox. Several areas traversed by the expedition became depopulated, potentially by disease caused by contact with the Europeans. Seeing the high fatalities and devastation caused, many natives would have fled the populated areas for the surrounding hills and swamps. In some areas, the social structure would have changed because of high population losses due to epidemics.[68] However, recent scholars have begun to question whether the expedition brought novel disease at all. The arrival of many diseases, aside from malaria, is disputed and they may not have entered the region until much later.[69] The first documented smallpox epidemic in the southeast arrived in 1696, and Mississippian social structures persisted in some parts of the region until the 18th century.[70]

The records of the expedition contributed greatly to European knowledge about the geography, biology, and ethnology of the New World. The de Soto expedition's descriptions of North American natives are the earliest-known source of information about the societies in the Southeast. They are the only European description of the culture and habits of North American native tribes before these peoples encountered other Europeans. De Soto's men were both the first and nearly the last Europeans to witness the villages and civilization of the Mississippian culture.

De Soto's expedition led the Spanish crown to reconsider Spain's attitude toward the colonies north of Mexico.[citation needed] He claimed large parts of North America for Spain.

Namesakes

[edit]

Many parks, towns, counties, and institutions have been named after Hernando de Soto, to include:

Places

[edit]- De Soto, Georgia

- De Soto, Illinois

- De Soto, Iowa

- De Soto, Kansas

- De Soto, Mississippi

- De Soto, Missouri

- De Soto, Nebraska

- De Soto, Wisconsin

- DeSoto, Texas

- DeSoto Caverns, Alabama

- DeSoto County, Florida

- DeSoto County, Mississippi, and its county seat, Hernando

- DeSoto Falls, in DeSoto State Park, Alabama

- DeSoto Falls, in Lumpkin County, Georgia

- DeSoto Lake, Georgia

- De Soto National Forest, in Mississippi

- De Soto National Memorial, near Bradenton, Florida, marks the possible location of Espiritu Santo, the point of disembarkation for the expedition.

- DeSoto Parish, Louisiana

- DeSoto Site Historic State Park, Florida

- DeSoto State Park, Alabama

- Fort De Soto Park in Pinellas County, Florida, named in turn for the 19th-century coastal fortifications at the site

- Hernando, Mississippi

- Hernando, Florida

- Hernando County, Florida

Other

[edit]- DeSoto automobile line developed by the Chrysler Corporation

- De Soto Heritage Festival

- DeSoto Central High School, in Southaven, Mississippi

- DeSoto County High School, in Arcadia, Florida

- DeSoto Hilton Hotel, Savannah, Georgia

- De Soto High School, in De Soto, Kansas

- De Soto High School, in De Soto, Missouri

- DeSoto High School, in DeSoto, Texas

- De Soto High School, in De Soto, Wisconsin

- Hernando de Soto Bridge, which carries Interstate 40 across the Mississippi River at Memphis (opened in 1973)

- PS 130, Hernando Desoto, a public school in New York City

- The De Soto School, a private school in Helena, Arkansas

- USS De Soto (1859), a Navy steamer that served during the American Civil War and in the West Indies.

- USS De Soto (1860), a riverboat that was renamed General Lyon on 24 October 1862.

- USS DeSoto County (LST-1171)

- De Soto Avenue, in Los Angeles, California

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Leon, P., 1998, The Discovery and Conquest of Peru: Chronicles of the New World Encounter, edited and translated by Cook and Cook, Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 978-0822321460

- ^ "De Soto". Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ Blanton, Dennis B. (2020). Conquistador's Wake: Tracking the Legacy of Hernando de Soto in the Indigenous Southeast. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-5637-2.

- ^ Hudson, Charles (15 January 2018). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South's Ancient Chiefdoms. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-5290-9.

- ^ a b Morison, Samuel (1974). The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages, 1492–1616. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ "De Soto dies in the American wilderness". Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Muñoz de San Pedro, Miguel; Lamb, Ursula (1965). "Note about the Birthplace of Hernando de Soto". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 44 (1/2): 45–50. ISSN 0015-4113. JSTOR 30147725. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ Charles Hudson (1997). p. 39.

- ^ Prescott, W.H., (2011) The History of the Conquest of Peru, Digireads.com Publishing, ISBN 978-1420941142

- ^ MacQuarrie. pp. 57–68, 71–72, 91–92.

- ^ Von Hagen, Victor W., 1955, "De Soto and the Golden Road", American Heritage, August 1955, Vol. VI, No. 5, American Heritage Publishing, New York pp. 32–37

- ^ MacQuarrie. pp. 96, 106, 135, 138, 145, 169.

- ^ Yupanqui, T.C., 2005, An Inca Account of the Conquest of Peru, Boulder: University Press of Colorado, ISBN 978-0870818219

- ^ Von Hagen, Victor W., 1955, "De Soto and the Golden Road", American Heritage, August 1955, Vol. VI, No. 5, American Heritage Publishing, New York, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Davidson, James West. After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection Volume 1. McGraw Hill, New York (2010), Chapter 1, pp. 1, 3.

- ^ a b Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0820318884.

- ^ De Soto Trail: National Historic Trail study: Final Report (PDF). National Park Service Southeast Regional Office. 1990. pp. 9, 28. OCLC 22338956.

- ^ Manatee County History Archived 21 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Manatee Florida Chamber of Commerce.

- ^ Sylvia Flowers, "DeSoto's Expedition", U.S. National Park Service, 2007, webpage: NPS-DeSoto.

- ^ Boyer III, Willet A. (2010). The Acuera of the Oklawaha River Valley: Keepers of Time in the Land of the Waters (PDF) (dissertation). University of Florida. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Boyer III, Willet (2017). "The Hutto/Martin Site of Marion County, Florida, 8MR3447: Studies at an Early Contact/Mission Site". The Florida Anthropologist. 70 (3): 122–139. On-line as"The Hutto/Martin Site of Marion County, Florida, 8MR3447: Studies at an Early Contact/Mission Site". academia.edu. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Boyer III, Willet (2015). "Potano in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries: New Excavations at the Richardson/UF Village Site, 8AL100". The Florida Anthropologist 2015 68 (3–4).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) On-line as"Potano in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries: New Excavations at the Richardson/UF Village Site, 8AL100". academia.edu. 23 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016. - ^ "The Parkin Site: Hernando de Soto in Cross County, Arkansas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ "Parkin Archeological State Park-Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ A Narrative of the Expedition of Hernando de Soto into Florida Published at Evora in 1557. Internet Archive. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Altman, Ida (1997). "An Official's Report: The Hernandez de Biedma Account". In Patricia Kay Galloway (ed.). The Hernando de Soto Expedition: History, Historiography, and "Discovery" in the Southeast. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-8032-7122-7. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Milanich, Jerald T.; Hudson, Charles (1993). Hernando de Soto and the Indians of Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 6–8. ISBN 0-8130-1170-1.

- ^ Lankford, George E. (1993). "Legends of the Adelantado". In Young, Gloria A; Michael P. Hoffman (eds.). The Expedition of Hernando de Soto West of the Mississippi 1541–1543. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. p. 175. ISBN 1-55728-580-2. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ Milanich, Jerald T.; Hudson, Charles (1993). Hernando de Soto and the Indians of Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-8130-1170-1.

- ^ Charles, Hudson; Chaves, Tesser Carmen, eds. (1994). The Forgotten Centuries-Indians and Europeans in the American South 1521 to 1704. University of Georgia Press.

- ^ Robert S. Weddle (2006). "Soto's Problems of Orientation". In Galloway, Patricia Kay (ed.). The Hernando de Soto Expedition: History, Historiography, and "Discovery" in the Southeast (New ed.). University of Nebraska Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-8032-7122-7. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513–1763. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. p. 6. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8.

Milanich, Jerald T. (2004). "Early Groups of Central and South Florida". In R. D. Fogelson (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast Vol. 14. Smithsonian Institution. p. 213.

DeSoto's Florida Trails – retrieved 5 September 2008 - ^ Sloan, David; Duncan, David Ewing (1996). "Hernando de Soto: A Savage Quest in the Americas". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 55 (3): 327. doi:10.2307/40030985. ISSN 0004-1823. JSTOR 40030985.

- ^ "Florida of the Inca | Early Americas Digital Archive (EADA)". eada.lib.umd.edu. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ Noszky, H. von (1909). "An Indian Battlefield Near Melrose". Florida Historical Quarterly. 2 (1): 47–48. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ Seibert, David. "De Soto in Georgia". GeorgiaInfo: an Online Georgia Almanac. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ Seibert, David. "De Soto in Georgia". GeorgiaInfo: an Online Georgia Almanac. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Fernbank Museum of Natural History (5 November 2009). "Archaeologists Track Infamous Conquistador Through Southeast". Science Daily. ScienceDaily LLC. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Pousner, Howard (6 November 2009). "Fernbank archaeologist confident he has found de Soto site". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission. John R. Swanton with an Introduction by Jeffrey P. Brain. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., 1985.

- ^ Blanton, DB (2020). Conquistador's wake : tracking the legacy of Hernando de Soto in the indigenous Southeast. University of Georgia Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0-8203-5635-8.

- ^ "Heritage History – Products". www.heritage-history.com. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ a b "The Old Mobile Project Newsletter" (PDF). University of South Alabama Center for Archaeological Studies.

- ^ Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press. pp. 230–232.

- ^ a b Higginbotham, Jay (2001). Mobile, The New History of Alabama's First City. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ^ Clayton, Lawrence A.; Knight, Vernon J.; Moore, Edward C. (1993). The De Soto Chronicles: The Expedition of Hernando De Soto to North America in 1539–1543. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press.

- ^ Tony Horwitz (2009). A Voyage Long and Strange: On the Trail of Vikings, Conquistadors, Lost Colonists, and Other Adventurers in Early America. Macmillan. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-312-42832-7. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ Quackenbos, George Payn (1864). Illustrated School History of the United States and the Adjacent Parts of America: From the Earliest Discoveries to the Present Time ... D. Appleton & Company.

- ^ Brown, Ian W. (2008). "Chapter 16. Culture Contact Along the I-69 Corridor: Protohistoric and Historic Use of the Northern Yazoo Basin, Mississippi". In Rafferty, Janet; Peacock, Evan (eds.). Time's River: Archaeological Syntheses from the Lower Mississippi Valley. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-8173-8112-7.

- ^ Flowers, Judith Coleman (2016). Clarksdale and Coahoma County. Arcadia. ISBN 978-1439655030.

- ^ Marley, David (1998). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present. ABC-CLIO. p. 45. ISBN 978-0874368376.

- ^ McNutt, Charles H. (1996). McNutt, Charles H. (ed.). The Central Mississippi Valley: A Summary. University of Alabama Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-0817308070.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Foti, Tom (1975). Arkansas: Its Land and People (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Environmental Education Office, Arkansas State Dept. of Education. pp. 21–22.

- ^ Charles Hudson (1997). pp. 320–325.

- ^ Carter, Cecile Elkins. Caddo Indians: Where We Come From. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001: 21. ISBN 0-8061-3318-X

- ^ a b Mitchem, Jeffrey M. (1 November 2023). "Hernando de Soto (1500?–1542)". CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ a b Charles Hudson (1997). pp. 349–352 "Death of de Soto".

- ^ "Hernando de Soto". Stopping Points Historical Markers & Points of Interest. 27 July 2009. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism. "Hernando de Soto Historical Marker". Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ a b Robert S. Weddle. "Moscoso Alvarado, Luis de". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- ^ Davidson, James West. After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection Volume 1. McGraw Hill, New York 2010, Chapter 1, p. 3

- ^ "Martin/de Soto Site History". Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ Galloway, Patricia (2006). The Hernando de Soto Expedition: History, Historiography, and "Discovery" in the Southeast. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 172–175. ISBN 978-0-8032-7122-7.

- ^ Joseph C. Porter. "Explorers Are You: Tar Heel Junior Historians, Pigs, and Sir Walter Raleigh" (PDF). North Carolina Museum of History. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ Tina Easley. "Razorbacks [Hog]". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ John Pukite (1999). A Field Guide to Pigs. Falcon. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-56044-877-8.

- ^ Josephy, Alvin M. Jr. (1994). 500 Nations, An Illustrated History of North American Indians. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 142–149. ISBN 0-679-42930-1.

- ^ Josephy, Alvin M. Jr. (1994). 500 Nations, An Illustrated History of North American Indians. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 152–153. ISBN 0-679-42930-1.

- ^ Beyond Germs : Native Depopulation in North America. Catherine M. Cameron, Paul Kelton, Alan C. Swedlund. Tucson. 2015. ISBN 978-0-8165-0024-6. OCLC 907132534.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Kelton, Paul (2007). Epidemics and Enslavement: Biological Catastrophe in the Native Southeast, 1492–1715. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1557-3.

Further reading

[edit]Chronicles (in English translations)

[edit]- Clayton, Lawrence A.; Knight, Vernon James Jr.; Moore, Edward C. (1993). The De Soto Chronicles, The Expedition of Hernando de Soto to North America in 1539–1543. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0824-7.

- Edward Gaylord Bourne, ed. (1904). Narratives of the career of Hernando de Soto in the conquest of Florida as told by a knight of Elvas, and in a relation by Luys Hernandez de Biedma, factor of the expedition Volume I. New York: A. S. Barnes and Company. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- Edward Gaylord Bourne, ed. (1904). Narratives of the career of Hernando de Soto in the conquest of Florida as told by a knight of Elvas, and in a relation by Luys Hernandez de Biedma, factor of the expedition Volume II. New York: A. S. Barnes and Company. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- Garcilaso de la Vega, el Inca (1881). Florida of the Inca. Philadelphia: Robert M. Lindsay. Retrieved 23 November 2013. Translated by E. Barnard Shipp.

- Garcilaso de la Vega, el Inca (1951). The Florida of the Inca. Austin: University of Texas Press. Translated by John and Jeanette Varner.

Histories

[edit]- King, Grace Elizabeth (1914). "De Soto and his men in the land of Florida" (PDF).

- Duncan, David Ewing (1995). Hernando de Soto : a Savage Quest in the Americas. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-517-58222-8.

- Schaeffer, Kelly. Disease and de Soto: A Bioarchaeological Approach to the Introduction of Malaria to the Southeast US" (University of Arkansas, 2019) online.

- Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun : Hernando De Soto and the South's Ancient Chiefdoms. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-1888-4.

- Albert, Steve: Looking Back......Natural Steps; Pinnacle Mountain Community Post 1991.

- Henker, Fred O., M.D. Natural Steps, Arkansas, Arkansas History Commission 1999.

- Jennings, John. (1959) The Golden Eagle. Dell.

- MacQuarie, Kim. (2007) The last days of the Incas. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6049-7

- Maura, Juan Francisco. Españolas de ultramar. Valencia: Universidad de Valencia, 2005.

- "American Conquest, The Oldest Record of Native America". Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- "The De Soto Chronicles Volume I, by Clayton, Knight, & Moore 1994". Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

Memory and historiography

[edit]- Blanton, Dennis B. Conquistador's Wake: Tracking the Legacy of Hernando de Soto in the Indigenous Southeast (U of Georgia Press, 2020) online review

- van de Logt, Mark. "The Old Man with the Iron-Nosed Mask:" Caddo Oral Tradition and the De Soto Expedition, 1541–42"." Western Folklore (2016): 191–222. online

- Wesson, Cameron B. "de Soto (Probably) Never Slept Here: Archaeology, Memory, Myth, and Social Identity." International Journal of Historical Archaeology 16.2 (2012): 418–435.

External links

[edit]- Hernando de Soto Profile and Videos – Chickasaw.TV

- Hernando de Soto in the Conquest of Central America

- De Soto Memorial in Florida

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. VII (9th ed.). 1878. pp. 131–132.

- "De Soto, Fernando". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- "De Soto, Fernando". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- "Soto, Ferdinando de". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 435–436.

- The chequered origins of chess in Peru: the Inca emperor turned pawn

- Spanish slave owners

- Spanish explorers of North America

- Spanish explorers of South America

- Explorers of the colonial Southwest of the United States

- 1496 births

- 1542 deaths

- 16th-century Spanish explorers

- Extremaduran conquistadors

- People from Sierra Suroeste

- Governors of Cuba

- Colonial United States (Spanish)

- Spanish West Indies

- Explorers of the United States

- Explorers of Spanish Florida

- Pre-statehood history of North Carolina

- Pre-statehood history of South Carolina

- Pre-statehood history of Georgia (U.S. state)

- Pre-statehood history of Tennessee

- Pre-statehood history of Alabama

- Pre-statehood history of Mississippi

- Pre-statehood history of Arkansas

- 1540s in New Spain

- 1540s in North America

- 16th-century Spanish military personnel