Iron Man

| Tony Stark Iron Man | |

|---|---|

Iron Man as seen on the variant cover of Tony Stark: Iron Man #2 (July 2018). Art by Mark Brooks. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Marvel Comics |

| First appearance | Tales of Suspense #39 (December 1962) |

| Created by | |

| In-story information | |

| Full name | Anthony Edward Stark |

| Place of origin | Long Island, New York |

| Team affiliations | |

| Partnerships | |

| Abilities |

|

Iron Man is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Co-created by writer and editor Stan Lee, developed by scripter Larry Lieber, and designed by artists Don Heck and Jack Kirby, the character first appeared in Tales of Suspense #39 in 1962 (cover dated March 1963) and received his own title with Iron Man #1 in 1968. Shortly after his creation, Iron Man became a founding member of the superhero team, the Avengers, alongside Thor, Ant-Man, the Wasp, and the Hulk. Iron Man stories, individually and with the Avengers, have been published consistently since the character's creation.

Iron Man is the superhero persona of Anthony Edward "Tony" Stark, a businessman and engineer who runs the weapons manufacturing company Stark Industries. When Stark was captured in a war zone and sustained a severe heart wound, he built his Iron Man armor and escaped his captors. Iron Man's suits of armor grant him superhuman strength, flight, energy projection, and other abilities. The character was created in response to the Vietnam War as Lee's attempt to create a likeable pro-war character. Since his creation, Iron Man has been used to explore political themes, with early Iron Man stories being set in the Cold War. The character's role as a weapons manufacturer proved controversial, and Marvel moved away from geopolitics by the 1970s. Instead, the stories began exploring themes such as civil unrest, technological advancement, corporate espionage, alcoholism, and governmental authority.

Major Iron Man stories include "Demon in a Bottle" (1979), "Armor Wars" (1987–1988), "Extremis" (2005), and "Iron Man 2020" (2020). He is also a leading character in the company-wide stories Civil War (2006–2007), Dark Reign (2008–2009), and Civil War II (2016). Additional superhero characters have emerged from Iron Man's supporting cast, including James Rhodes as War Machine and Riri Williams as Ironheart, as well as reformed villains, Natasha Romanova as Black Widow and Clint Barton as Hawkeye. Iron Man's list of enemies includes his archenemy, the Mandarin, various supervillains of communist origin, and many of Stark's business rivals.

Robert Downey Jr. portrayed Tony Stark in Iron Man (2008), the first film of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and continued to portray the character until his final appearance in Avengers: Endgame (2019). Downey's portrayal popularized the character, elevating Iron Man into one of Marvel's most recognizable superheroes. Other adaptations of the character appear in animated direct-to-video films, television series, and video games.

Publication history

Creation

Following the success of the Fantastic Four in 1961 and the subsequent revival of American comic books featuring superheroes, Marvel Comics created new superhero characters. Stan Lee developed the initial concept for Iron Man.[1] He wanted to design a character who should be unpalatable to his generally anti-war readers but to make them like the character anyway.[2] Iron Man was created in the years after a permanent arms industry developed in the United States, and this was incorporated into the character's backstory.[3] The character was introduced as an active player in the Vietnam War. Lee described the national mood toward Vietnam during Iron Man's creation as "a time when most of us genuinely felt that the conflict in that tortured land really was a simple matter of good versus evil".[4]

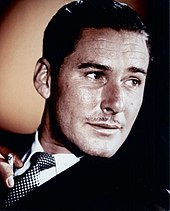

Larry Lieber developed Iron Man's origin and wrote the first Iron Man story, while Jack Kirby and Don Heck were responsible for the initial design.[1][5] Lee modeled Iron Man after businessman Howard Hughes, invoking his physical appearance, his image as a businessman, and his reputation as an arrogant playboy.[6] Kirby and Heck then incorporated elements of the actor Errol Flynn's physical appearance in the design.[7] When first designing the character, Lee wanted to create a modernized Arthurian knight.[8] Kirby initially drew the Iron Man armor as a "round and clunky gray heap", and Heck modified the design to incorporate gadgets such as jets, drills, and suction cups.[9][10] The Iron Man character was created at a time when comic book characters were first depicted struggling with real-life problems, and his heart injury was an early example of a superhero with a physical disability.[11]

Early years

Iron Man's earliest stories were published in the monster-themed anthology series Tales of Suspense. Marvel premiered several superheroes this way in the 1960s as superhero comics became more popular than traditional science-fiction and horror comics.[9][12] Iron Man's first appearance, "Iron Man is Born!", appeared in Tales of Suspense #39, released in December 1962 with a March 1963 cover date.[12] Though the Iron Man armor was gray in its first appearance, Marvel changed it to gold because of issues with printing.[5] Lee initially delegated the writing duties to other creators at Marvel, but he felt their work was substandard; as with his other characters, Lee reclaimed control of Iron Man so he could write the stories himself.[13]

Once Marvel's distributor allowed the company more monthly releases, The Avengers (1963) was developed as a new comic book series.[14] Iron Man was one of the five characters who formed the titular superhero team.[15] By 1965, the difficulty of maintaining continuity between The Avengers and the members' solo titles prompted Lee to temporarily write the original cast out of The Avengers, including Iron Man.[16]

Heck continued as the primary Iron Man artist until 1965, as Kirby had obligations to other Marvel properties.[9][10] As part of a shuffling to match artists with the characters they were most suited for, Steve Ditko briefly became the artist for Iron Man.[17] He was responsible for only three issues in late 1963, but in this time he redesigned Iron Man's suit from fully gold to the red and gold color scheme that became the character's primary image.[18] Iron Man's recurring nemesis, the Mandarin, first appeared shortly after in Tales of Suspense #50 (1964).[19] By this time, the science-fiction and horror stories were phased out from Tales of Suspense, and the series ran only Iron Man and Captain America stories.[12] Gene Colan became the artist for Iron Man in January 1966, bringing with him an expressionist style.[18]

For the first five years of publication, Iron Man represented the United States in Cold War allegories.[4][20] Growing opposition to the American involvement in Vietnam prompted a shift in Iron Man's characterization, which was part of a larger push by Marvel in the late 1960s to be more apolitical.[4][21] Over the years, the letters to the editor column in several issues saw extensive political debate.[22] Lee shifted the stories' focus to espionage and domestic crime, incorporating Marvel's fictional intelligence agency S.H.I.E.L.D. He also incorporated the villains of other Marvel heroes, avoiding Iron Man's primarily communist rogues' gallery and rewriting some of Iron Man's communist villains to have personal motivations independent of their communist allegiances.[23]

Iron Man was one of several characters whom Marvel gave a full-length dedicated series in 1968.[24] Marvel combined the final issues of Tales of Suspense and the Sub-Mariner's Tales to Astonish into a one-shot special, Iron Man and Sub-Mariner.[25] Iron Man then began its run under writer Archie Goodwin.[26] Goodwin reintroduced political themes slowly over the following years, with a focus on domestic issues like racial conflict and environmentalism rather than geopolitics.[27] George Tuska started drawing the character in Iron Man #5 (1968) and intermittently served as artist for much of the 1970s.[28][29] In total, he drew over one hundred issues for the character.[30]

1970s

I don't feel Tony Stark is a dinosaur, a creature unable to change before the weight of time crushes him aside. Yeah, it is hard in 1977 to praise a millionaire industrialist, playboy and former munitions-manufacturer—but it isn't impossible to change that image. Which is what I plan to do.

When Goodwin became Marvel's editor-in-chief, he assigned Gerry Conway as the writer for Iron Man.[32] Conway was the first of several writers in a four-year effort to reform Iron Man, beginning in 1971, with stories that directly addressed the character's history as a weapons manufacturer.[33] These stories were especially prominent during a run by Mike Friedrich, in which corporate reform of Stark Industries was a recurring subplot.[34]

Iron Man was one of several Marvel characters who declined in popularity during the 1970s, and the series went a period of time without a dedicated writer until Bill Mantlo took over in 1977.[35] The following year, David Michelinie and Bob Layton took charge of the series, beginning with issue #116.[36][37] While inking the series, Layton used issues of GQ, Playboy, and electronics catalogues as visual references,[38] which he and Michelinie used to stay informed on developments in real world technology so the Iron Man armor would always be a more advanced version of what existed.[37] Layton was inspired by the vast collection of specialized outfits used by Batman when designing Iron Man's various armors.[39][40]

In Iron Man #117 and #118 (1978), Michelinie and Layton replaced many elements that developed over the series' run: they removed Iron Man's romantic interest Whitney Frost and Stark's robotic Life Model Decoy doubles, and they had Stark move to a different home.[41] They introduced Iron Man's new romantic interest, Bethany Cabe, as a feminist character who worked as his bodyguard.[42] Their goal was to push the character toward a more grounded, realistic portrayal.[43] The largest change they made was to make Iron Man an alcoholic, an unprecedented move for a major comic book hero, which led to the "Demon in a Bottle" story arc that ran from issues #120 to #128 (1979).[44] At the same time, they introduced the character Justin Hammer, who provided financial backing for several Iron Man villains.[45]

1980s and 1990s

Michelinie and Layton remained on the series until Iron Man #153 (1981).[46] Michelinie later said, "The reason I quit is that we felt we'd done everything with it that we'd set out to do."[47] Through the 1980s, writers for Iron Man focused on the character's role as a businessman, reflecting the economic changes associated with Reaganomics, and many of his challenges involved threats to his company.[48] Denny O'Neil was put in charge of Iron Man beginning with issue #158 (1982). His run explored Stark's psychology, having him relapse into alcoholism and suffer at the hands of business rival Obadiah Stane.[39] O'Neil wrote Stark out of the role entirely beginning with issue #170 (1983), having him temporarily retire as Iron Man and replacing him with his ally James Rhodes.[49] Stark was relegated as a side character until he returned to heroism in Iron Man #200 (1985).[50]

The 1987 "Armor Wars" story arc followed Iron Man as he reclaimed his technology, which Justin Hammer distributed to several villains.[51] This story blended the character's superhero and businessman aspects more directly when Stark sought legal recourse against his rivals.[48] Michelinie and Layton returned to the series with issue #215 (1988) through issue #232 (1989).[46] Again, they experimented with variations on the Iron Man armor[39] and focused on down to Earth stories with realistic situations.[47]

In 1990, Michelinie and Layton handed the series over to John Byrne, one of the most highly regarded comic book writers at the time. He wrote three story arcs across 20 issues: "Armor Wars II" (which had already been announced by Michelinie and Layton), "The Dragon Seed Saga", and "War Games".[52] Byrne revisited Iron Man's opposition to communism but portrayed it as less of a threat,[53] and he rewrote Iron Man's origin to remove references to communism and the Vietnam War. He lost interest in the series by 1992 as his collaborators John Romita Jr. and Howard Mackie had moved on to other projects.[52] Iron Man's supporting character War Machine was spun off into his own comic book series in 1994.[54]

The Iron Man series rejected broader ideological themes by the 1990s, and individualist values replaced Stark's allegiance to American democracy for its own sake. He remained anti-communist, reiterating his support for democracy and refusing to do business in China following the Tiannamen Square Massacre in 1989.[55] The absence of Cold War politics was not immediately replaced by another theme, and post-Cold War Iron Man stories often explored different ideas regarding technology for a short time before moving on.[56] When terrorism became more prominent in the public mind, writers shifted Iron Man's symbolism from anti-communism to anti-terrorism.[57]

As part of a company-wide reorganization in 1996, Marvel's major characters, including Iron Man, were given to former Marvel writers Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld in a profit-sharing agreement. Lee and Liefeld were given charge of the "Heroes Reborn" branding that renumbered Marvel's long-running periodicals at issue #1.[58] This new Iron Man series, labeled volume two, was set in an alternate universe created during the "Onslaught" event. It ran for 13 issues, written by Lee and Scott Lobdell and drawn by Whilce Portacio.[59][60] The following year, Marvel introduced the "Heroes Return" event to bring the characters back from the alternate universe, which again reset characters such as Iron Man to issue #1.[61][62] Kurt Busiek became the writer for volume three while Sean Chen was the artist.[59][63]

2000s

When the Ultimate Marvel imprint was created with reimagined versions of Marvel's characters, an alternate Iron Man appeared in 2002 with the Ultimates, the imprint's adaptation of the Avengers.[64] Marvel released a five-issue limited series, Ultimate Iron Man, featuring this character in 2005.[65]

Iron Man represented an attempt to define what a superhero was in the 21st century, following the September 11 attacks, implicitly likening the fear of terrorism to the fear of unregulated super-powered beings.[66] In 2004, Iron Man was a major character in the Avengers Disassembled event and subsequently became a founding member of the New Avengers.[67] Iron Man volume four began in 2005,[59] with Warren Ellis as the writer and Adi Granov as the artist. Its first story arc, "Extremis", saw Iron Man upgrade his body directly through the Extremis virus, giving him direct control over a biological armor.[65] The volume's first 14 issues carried the Iron Man title, while issues #15–32 (2007–2008) were titled Iron Man: Director of S.H.I.E.L.D.[59]

Iron Man led the pro-registration faction during the 2006 Civil War crossover event by Mark Millar and Steve McNiven.[68] In an allegory for the Patriot Act and government surveillance, Iron Man's pro-registration faction represented conservative support for government surveillance in the name of security and stood against Captain America's anti-registration faction that represented individualism and liberal opposition to government surveillance.[69] Iron Man believed in pragmatically choosing the lesser of two evils, whereas Captain America held an idealist approach, and both held these positions at great personal cost.[70] While Marvel was neutral between the characters, readers overwhelmingly saw Iron Man as the villain, being the stronger force that the underdog had to overcome.[71][72]

Iron Man appeared with the Mighty Avengers in 2007,[73] and his characterization in this era leaned into his identity as a futurist.[74] Marvel restarted Iron Man's comic book run with Invincible Iron Man in 2008, written by Matt Fraction and drawn by Salvador Larroca.[75] This series launched around the same time as the film Iron Man premiered,[76] and the Marvel Cinematic Universe developed while this run was in publication.[75]

2010s and 2020s

The Iron Man series reverted to the original numbering in 2011, when the overall 500th issue was published as Iron Man #500.[59] A concurrent series, Iron Man Legacy by Fred Van Lente, was launched in 2010 leading up to the release of the film Iron Man 2.[76] Iron Man was then one of several characters whose series was relaunched at issue #1 with the Marvel Now! branding following the 2012 Avengers vs. X-Men event,[77] written by Kieron Gillen.[78] The 2014 "AXIS" event led into the Superior Iron Man series by Tom Taylor, featuring Iron Man with a new reversed personality.[79]

A new Invincible Iron Man run written by Brian Michael Bendis and drawn by David Marquez began in 2015.[80] A simultaneous Iron Man series, International Iron Man, ran for seven issues in 2016 under Marvel's All-New, All-Different Marvel branding, also by Bendis. This series was meant to ensure Iron Man's status as a major character as All-New, All-Different developed.[81] A second Civil War event in 2016 portrayed Iron Man as an advocate of free will against Captain Marvel's determinism.[82]

As part of a broader trend by Marvel Comics to substitute its main characters with a diverse cast of original characters in the 2010s, Iron Man was temporarily replaced by Ironheart, a teenaged African-American girl who reverse-engineered the Iron Man armor, in 2016.[83] At the same time, the series Infamous Iron Man began publication with Dr. Doom as Iron Man.[84]

The series Tony Stark: Iron Man premiered in 2018 with the Fresh Start branding, written by Dan Slott and drawn by Valerio Schiti.[85] In 2020, Iron Man was relaunched in a new series, written by Christopher Cantwell and illustrated by CAFU, following the "Iron Man 2020" event. This series moved away from the developments and deviations made to Stark's character introduced over the previous years—including the more extravagant science fiction and soap opera plots—creating a clean slate for new story arcs in a traditional superhero setting.[86] The character was relaunched again in 2022 with Invincible Iron Man, written by Gerry Duggan and illustrated by Juan Frigeri.[87] A new volume was launched in October 2024, written by Spencer Ackerman and illustrated by Julius Ohta.[88]

Characterization

Fictional character biography

Anthony Edward "Tony" Stark was born in Long Island, New York. As a child, he inherited his family's business, Stark Industries when his parents were killed in a car crash.[89] Developing equipment for the U.S. military, he travels to a war zone to conduct a weapons test when he triggers a booby trap. His heart is critically injured by shrapnel, and he is captured by the communist Wong-Chu, who demands Stark build him a weapon. Stark instead builds a suit of armor that sustains his heart, becoming Iron Man.[18][9] The war zone Stark visited was changed retroactively multiple times by different writers to correspond with the character's age, which is explained by a "sliding scale of continuity" in which the timing of significant events in the world of Marvel may change. This conflict was the Vietnam War for the first decades of Iron Man's publication history.[90] This was changed to an unnamed Southeast Asian country in the 1990s,[91] and a conflict in the fictional country Siancong was ultimately created to justify the inconsistency.[92]

Iron Man returns to the United States and becomes a superhero, convincing the public Iron Man is Stark's bodyguard.[89] When he is called to stop the Hulk and learns Loki is behind the Hulk's attack, he joins forces with the Hulk, Thor, Ant-Man, and the Wasp to defeat Loki, and they agree to form a superhero team, the Avengers.[15] He also helps found the intelligence agency S.H.I.E.L.D., providing the organization with equipment.[89] Iron Man then undergoes surgery to replace the damaged portions of his heart, eliminating the need for his prosthetic chest plate.[93] As he came to regret his involvement in weapons manufacturing, Stark Industries is changed to Stark International, an electronics company that emphasizes environmentalism and ending world hunger.[94][89] S.H.I.E.L.D. attempts to take over the business and return it to weapons manufacturing. At the same time, Iron Man is framed for murder. These stresses cause him to begin drinking, and he develops alcoholism.[95] Though he gets sober, he relapses due to a plot orchestrated by his business rival Obadiah Stane.[89] Iron Man briefly loses his company to Stane, passes the Iron Man mantle to his ally James Rhodes,[49] and becomes homeless.[93] After Stark recovers, Stane adopts an armored suit and becomes the Iron Monger before being defeated. Iron Man then founds a space technology company, Stark Enterprises. When Iron Man learns Justin Hammer had acquired the Iron Man armor's technology, he seeks out all the other armors. The resulting fights leave Iron Man a fugitive, leading him to fake his death and then describe himself as a new Iron Man.[89]

When Iron Man is shot in the spine and paralyzed, he develops a new prosthesis that grants him mobility. This prosthesis is hacked and controlled remotely, causing neurological damage that appears for a time to kill him.[96] Rhodes temporarily becomes Stark's chosen successor as Iron Man. After returning, Immortus places Stark under his control and turns him evil. The Avengers bring an alternate Tony Stark from another reality to help defeat him. Iron Man is killed and the alternate Tony Stark becomes the new Iron Man, but Franklin Richards merges both versions into a single being when he rewrites reality. Stark's company was bought out at this point, so he started a consulting firm, Stark Solutions. His secret identity is revealed to the public shortly afterwards. He is then appointed Secretary of Defense until the Scarlet Witch alters his mind, causing him to behave drunkenly at the United Nations and leave in disgrace.[89] When Mallen becomes a threat through the Extremis project, Iron Man has Maya Hansen inject him with the Extremis virus, giving him a biological armor he can control with his mind.[97]

Iron Man serves as the Superhero Registration Act's enforcer upon its enactment, creating a schism between superheroes, with Iron Man leading proponents of registration against a group of resistors led by Captain America.[68] After the conflict, Iron Man becomes head of S.H.I.E.L.D.[98] The government dismantles S.H.I.E.L.D. after it fails to prevent an alien invasion, but Iron Man refuses to turn over the list of registered heroes to its corrupt successor agency H.A.M.M.E.R.[99] This agency is dismantled as well, and Iron Man organizes the Avengers to replace these agencies.[89] He founds a clean energy company, Stark Resilient, and fakes his death so his enemies will not threaten it. He joins the Guardians of the Galaxy for a time, and upon returning to Earth, he discovers he had actually been adopted by the Starks so their biological son could be hidden from an alien threat.[100]

While fighting Red Skull, a spell cast by Victor von Doom and the Scarlet Witch temporarily inverts the personalities of several heroes. The new morally corrupt Iron Man protects himself from the counterspell and takes over San Francisco to augment the residents with Extremis.[101] When a man is discovered who can see the future, the superhero community undergoes another schism, and Iron Man leads a team of heroes opposed to a predetermined justice system based on his ability.[82] The battle ends with Iron Man in a coma. A reformed Victor von Doom becomes Iron Man, while an artificial intelligence backup of Stark's mind guides a new armored superhero, Ironheart. Stark resumes his work as Iron Man after the technology in his body allows him to heal.[100] He then allies with Emma Frost and marries her to set a trap for their mutual enemy Feilong.[102]

Personality and motivations

We really thought about how we needed to give him a weakness. It wasn't hip to have him running out of energy and looking for a light socket every few pages, or having a heart attack every time Ultimo was fighting him. So we discussed it and we thought that we would give him the corporate man's disease [alcoholism]. Something that would always haunt him.

Iron Man is a businessman and entrepreneur who seeks to innovate and improve his technology,[6][104] both for society's benefit and his own.[105][106] Iron Man is one of many Marvel heroes with a genius-level intellect,[107] but his focus on societal application alongside hard science distinguishes him from other heroes.[107] The character is a futurist, and he works to identify solutions for problems that have yet to emerge. This preemptive problem-solving was a driving force in his organization of the Avengers and later in his support for the Superhero Registration Act during the Civil War event.[108]

Stark's intelligence and engineering skills allowed him to construct the Iron Man armor, and he believes this justifies his authority over the armor and who uses it.[109] While Iron Man sometimes develops equipment for other superheroes, he is selective about who can use the armor, trusting only a few close allies.[110] In the 2008 story "The Five Nightmares", Iron Man narrates his five greatest fears: relapse into alcoholism, reproduction of the Iron Man technology, other people becoming Iron Man, the technology becoming disposable, and that someone else would be distributing this technology. Besides the danger such scenarios pose, they all represent fear of losing power over himself or his technology.[111]

Iron Man finds machines easier to interact with than humans, believing machines can be more easily controlled and repaired.[89] This leads him to engage in self-destructive behavior, giving his relationships as Tony Stark lower priority and failing to be accountable for his creations as Iron Man.[112] His isolation comes to him from two directions, with both his celebrity status and his role as Iron Man making personal relationships difficult.[113] Through both poor decisions and bad luck, he is unable to maintain romantic relationships despite his wealth and talents.[114] Writer Dennis O'Neil described the Iron Man armor as "a psychological crutch preventing him from dealing with his own inner demons".[39] He identifies with the Iron Man armor as an extension of himself, believing the image it presents is his own image, and he considers himself responsible any time someone uses the technology.[115]

Iron Man behaves differently as a superhero and as a civilian, engaging in courageous and selfless acts as Iron Man but morally ambiguous behavior as Stark.[116] The character represents a traditional understanding of American masculinity as a businessman and a playboy, particularly as it was seen in the Cold War.[117][118] This characterization also manifests in negative traits that were prominent in early Iron Man stories, including belligerence, negligence, and misogyny.[119] Stark has several character flaws emerging from his impulsivity and arrogance, engaging in vices that include excessive drinking, partying, and womanizing.[120][116][121]

Iron Man's heart injury was prominent in his early characterization, causing him to isolate himself so as not to reveal his injury or his secret identity.[10] This weakness was a threat to his autonomy and his masculinity.[122] As real-world medical technology made heart injuries less fatal, writers introduced neurological damage[123] and alcoholism as other medical weaknesses.[124][125] Despite this, Iron Man considers himself lucky and believes he lives "a good life", attributing this to his money, friendships, engineering skills, and recovering health.[126]

Iron Man's belief in progress sometimes manifests as opposition to the press and politicians, whose attempts to keep him accountable hamper his efforts as a superhero.[127] He is conflicted between his support for the rule of law and his moral beliefs in doing what he feels must be done for the greater good. When he engages in unsanctioned attacks against those who co-opted his technology in the "Armor Wars" story, he describes it as "a tough decision; perhaps the toughest in my life".[128] The character's morally ambiguous nature can make him more accessible to readers relative to other superheroes who are more inherently virtuous.[129][130]

Themes and motifs

Politics and economics

Iron Man was more overtly political than other Silver Age Marvel characters.[131] Lee wrote the character to represent liberal capitalism, fighting against communism and other anti-democratic forces.[132][133][134] Though anti-communist sentiments were present throughout Marvel Comics, they appeared most prominently in Iron Man stories.[135] After Marvel shifted away from addressing foreign conflicts toward the end of the 1960s, Iron Man was portrayed as a liberal who was skeptical of the U.S. government, yet also opposed radicalism; at the time associated with 1960s counterculture.[136] Marvel portrayed Iron Man as more self-doubting, questioning when the use of force is justified against communism.[137][138] By 1975, Iron Man opposed the Vietnam War,[136] which gave the character a new motivation in making up for his promotion of violence in the past.[139] Iron Man's use of his vast resources as a protector was reframed as a cautionary tale, in which these resources could be co-opted to do harm. His motivation for providing weapons to the government was retroactively changed so Stark only got involved because he believed it would end the war more quickly.[140] Over time, writers portrayed Iron Man as a philanthropist.[141]

The dual role of Iron Man and Tony Stark allows for the examination of both the perspective of an individual inventor and that of the bureaucracy of governments and corporations, respectively.[142] His business Stark Industries is depicted as a force for good that advances scientific knowledge through capitalist innovation.[106] The Iron Man persona itself, as well as the technology Iron Man uses, are proprietary assets owned by Stark Industries.[143] Reflecting his characterization as a businessman, Iron Man stories often invoke themes of economic competition, seeing him face characters who try to develop better versions of the Iron Man armor.[144] Many of Iron Man's challenges involve corrupt business rivals and corporate espionage.[53]

Technology

Technology and its influence on society are common themes in Iron Man stories,[29][145] and various writers have portrayed him as a technological marvel since his earliest appearances.[146] The character's use of technology, both as a weapons manufacturer and as Iron Man, explores problems that arise from progress and advancement,[147] including misuse of technology and the implications of cybernetics.[148] Iron Man's position within the suit allows for discussion regarding automation versus human oversight of technology,[149] and it reflects the debate on how new technologies are incorporated into public and military use, including the use of exoskeletons and battle suits.[150] These technological themes are explored through a modern lens during the "Extremis" story arc, which incorporates the idea of human enhancement through biotechnology.[151][152]

Depictions of technology in Iron Man stories have often endorsed its use to alter the natural world.[153] This is in contrast with Silver Age Marvel stories, where radiation and other technological advancements were portrayed as dangerous.[106][154] Iron Man's engineering talent is key to his heroism, unlike other heroes who use engineering to supplement superhuman abilities.[155] This makes it more plausible that something like Iron Man could exist in the real world, as it is only technological advancement that separates Iron Man from reality.[156][157] Iron Man's power of flight is especially significant in the technology's symbolism, as it associates traditional heroic imagery with a technological component, giving this power to a man who created it himself in a transcendental fashion.[158]

Armor

Iron Man does not have any superhuman abilities. Instead, he derives his strength from a powered armor of his own design.[159] The armor is equipped with various weapons, which include "repulsor rays" in each palm that project particle beams as well as a stronger "unibeam" on his chest.[99] As of 2010, Marvel described Iron Man's armor as being able to lift 100 tons and to fly at Mach 8.[99]

Marvel initially depicted the armor as powered by transistors,[18] but this was replaced with integrated circuits as real-world technology advanced.[160] New designs have further miniaturized the technology, ultimately incorporating nanotechnology.[161] Developments in the armor's design often reflect real-world advances in technology and trends in science fiction.[162] The changing nature of the armor allows artists to make frequent changes to the character's appearance without controversy.[145] Iron Man has also created specialized models for specific purposes,[163] including space armor, stealth armor, and deep sea armor,[164] as well as the Hulkbuster armor to engage in combat with the Hulk.[163]

Prior to Iron Man's surgery, the armor's primary function was to produce a magnetic field that protected his heart from the shrapnel in his body. His efforts to keep it charged and to keep it secret drove the story's plot.[165] From its first appearance, Stark has controlled the armor by linking it to his brainwaves,[166] and he must calibrate it to any allies who use it.[167] The armor is often shown to have some method of shrinking it down to make it portable when not being used.[168]

Iron Man stories contrast the armor's strength and the vulnerability of the human inside it.[169][165] The armor protects Iron Man externally from attacks, but it also protected him internally when it kept his heart beating.[166] The form-fitting design of many Iron Man armors emphasizes this with a human figure in an otherwise robotic-looking character.[132]

During the "Extremis" story arc, Iron Man adopted a biotechnological armor embedded in his DNA and stored in his bones. This allowed him to summon the armor from within his body and control it with his mind, effectively giving him superhuman abilities. This reduced the input lag between his brain and his armor, allowed him to mentally interface with any technology in the world, and gave him the focus to engage in several unrelated tasks at once.[170][171][172] The Extremis technology also converted Iron Man's mind into a digital storage device to create a back up of his memories. It also presented a weakness, as Iron Man's archnemesis Mandarin was able to access and manipulate the data.[101] Iron Man gave up the Extremis armor after it was compromised with a computer virus by the Skrulls, who used it to disable Earth's defenses during an invasion.[173]

Supporting characters

Allies

Pepper Potts is a Stark Industries employee who Stark promoted to his executive assistant.[174] The original portrayal of the character was that of a simple love interest and damsel in distress.[114] She came to manage the business herself, as Stark had little interest in his responsibilities.[174] When Stark became Iron Man and took responsibility for his company, she taught him how to manage the business.[89] When Pepper was injured by an explosion and received a heart injury similar to Iron Man's, he installed the arc reactor technology in her.[175] She eventually became the CEO of Stark Industries.[176] Iron Man secretly worked on a suit of armor to be powered by her arc reactor, and she discovered it in a Stark Industries lab while she had control of the company. Taking the armor, she became the superhero Rescue.[177]

James Rhodes was an employee of Stark's.[57] He first appeared in 1979 and was developed as a supporting character in 1981.[178] He briefly became Iron Man while Stark was relapsing on alcoholism.[49] Later on, when Stark was near death, he gave Rhodes his corporation and the War Machine armor.[179] Stark let Rhodes keep the armor, and Rhodes became the superhero War Machine.[180] Rhodes' dependency on Iron Man for his armor often constrains him as a supporting character to Stark, even in solo War Machine stories.[181]

Happy Hogan was hired as Stark's chauffeur after saving his life, and Happy later deduced Stark was Iron Man.[182] Iron Man has other allies through his affiliation with the Avengers, including close personal relationships with Captain America, Ant-Man, and the Wasp.[183] As Tony Stark, he is the benefactor of the Avengers, providing their headquarters at Avengers Mansion.[184] Stark's butler, Edwin Jarvis, works for both Iron Man and the Avengers.[185] During a period without Pepper, Stark hired a new secretary, Mrs. Arbogast.[186] Iron Man is also supported by his artificial intelligence companions Jocasta[185] and F.R.I.D.A.Y.[101] His association with S.H.I.E.L.D. sees him working with its agents and leadership, including Nick Fury and Maria Hill.[176] He has taken on other heroes as sidekicks, including Spider-Man and Jack of Hearts.[89]

Other characters in the Marvel Universe have taken up the Iron Man mantle besides Stark, including James Rhodes[49] and Victor von Doom.[100] The Iron Man armor itself came to life in the "Mask in the Iron Man" storyline, becoming violent before sacrificing itself to save Stark's life.[187][188]

Romantic interests

Iron Man has had many romantic interests, most of which only last a short time.[89] In the original Tales of Suspense run, Lee established a love triangle in which Stark and Happy were both romantically interested in Pepper.[189][10] Happy eventually married Pepper.[182] The series then introduced Roxie Gilbert, the sister of the villain Firebrand, as a romantic interest in the early 1970s. She was a foil for both Iron Man and Firebrand, representing non-violent activism.[190]

The women associated with Iron Man became more independent as second-wave feminism encouraged Marvel's writers to create stronger female characters.[191] Whitney Frost was Iron Man's romantic interest later in the 1970s until she turned against him as the villain Madame Masque.[41][192] Bethany Cabe became Stark's love interest in 1978 as part of an overhaul of Iron Man's supporting cast, and she supported him during his period of alcoholism.[95] Michelinie chose to remove Pepper as a love interest in favor of Cabe because he felt that Iron Man would be more interested in a strong woman.[186] She left Iron Man after he saved her husband, who was presumed dead.[89]

Stark was seduced by Indries Moomji, who was hired by Obadiah Stane to help ruin Stark, first appearing in issue #163 (1982).[193] He later partnered with Rumiko Fujikawa, the daughter of a businessman who took over Stark Enterprises.[89] Stark also began a relationship with his long time ally Janet van Dyne, the Wasp,[100] whom he had briefly dated in the past before she learned he was Iron Man.[89] A story arc in September 2023 saw Iron Man married to X-Men member Emma Frost as part of a plan to defeat the villain Feilong.[102]

Villains

Iron Man's earliest villains were often affiliated with the Soviet government or otherwise associated with communism.[194] In the first three years after Iron Man was created, one-third of his villains were communists.[195] Some of these enemies were Soviet counterparts of Iron Man, such as Titanium Man[131] and Crimson Dynamo,[196] while others held leadership positions in communist states, such as the Red Barbarian and the real-life Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev.[194] Khrushchev, like most communists in the series, was drawn in caricature style as a brute who only sought power.[197] Multiple communist villains, such as Crimson Dynamo, reformed and became heroes loyal to the United States to present Iron Man and liberal capitalism as more appealing and morally superior.[198] Two prominent Marvel heroes, Soviet spy Black Widow and American street criminal Hawkeye, were introduced as Iron Man villains before reforming as heroes.[199][200]

Marvel introduced the Mandarin as a Chinese villain, incorporating racist Yellow Peril themes and stereotypes regarding China.[201][202] Though he is an allegory for autocracy,[203] the Mandarin was not created as another communist villain.[204] Instead, any work he does with the Chinese government is purely in self-interest.[205] Later on, the Mandarin was retroactively established as the man behind the kidnapping that created Iron Man.[91] The Mandarin contrasts with Iron Man through his association with magic and mysticism instead of science and technology,[206][205] and because he was born into nobility unlike Iron Man, who is a self-made man in line with American ideals.[203]

Beginning in the 1970s, Iron Man faced villains who represented social conflict and unrest, such as the anarchist Firebrand and the corrupt businessman Guardsman.[207] He also faced villains representing concerns about technology, such as Ultimo.[208] Stark's business pursuits have invited several supervillains who oppose Stark Industries instead of just Iron Man.[180] These villains became prominent in the 1980s,[209] and they were amplified by backlash to consumerism that emerged in the 1990s.[53] Some of these villains wish to compete with the corporation and steal trade secrets, such as Spymaster, Whiplash, and Beetle. Others oppose the corporation on ideological grounds, such as Atom-Smasher.[180]

Tony Stark's chief business rival is Obadiah Stane. Stark's application of business as an altruistic pursuit is contrasted with Stane's application as a selfish pursuit.[134] Justin Hammer was introduced as another businessman to be Tony Stark's antithesis. Unlike Stark, Hammer avoids public attention and provides equipment for other villains instead of using it himself.[210] Other major villains include Shockwave, the Controller, the Mauler, and Stilt-Man.[209] A focus on terrorism introduced villains such as Zeke Stane, the son of Obadiah Stane who carried out terrorist attacks using suicide bombers.[211]

Alternate versions

Other versions of Iron Man exist in other universes as part of Marvel's multiverse. In the Ultimate Universe, an alternate version of Iron Man exists as a member of the Ultimates, the universe's counterpart of the Avengers.[212] Iron Man 2020 is the superhero persona of Tony's cousin-once-removed Arno Stark, who is from an alternate future in which superheroes vanished in the 1980s. After becoming Iron Man, Arno traveled back in time to the primary Marvel Universe.[213]

Reception and legacy

Iron Man's appearances in the 1960s saw mixed reception from readers, many of whom criticized the character for his association with the United States military and the controversial Vietnam War.[4][22] In response, Marvel rewrote the character in the 1970s to moderate his image and to have him directly reflect on his culpability in the harms caused by war.[33][137] According to Lee, Iron Man was the most popular hero when reading fanmail from female readers, which he attributed to both the character's charisma and his tragic nature.[214]

Many stories featuring the character have achieved critical acclaim. "Demon in a Bottle" in Iron Man #120–129 (1979) is celebrated as the definitive Iron Man story for exploring the depth of his character through his alcoholism. "Doomquest" in #149–150 (1981) is a popular favorite for its lighter tone and its establishment of a rivalry between Iron Man and Doctor Doom. "Armor Wars" in #225–232 (1987–1988) is credited for developing Iron Man's personality as someone willing to be more aggressive at the expense of his alliances and public trust. "Extremis" in Iron Man Vol. 4 #1–6 (2005–2006) is recognized as a landmark for a new modern era of Iron Man comics.[215][216][217][218] Other celebrated stories include "Deliverance" in Iron Man #182 (1984), the "Iron Monger Saga" in Iron Man #190–200 (1984–1985), and "World's Most Wanted" in Invincible Iron Man #8–19 (2009).[215][216][218] Iron Man's characterization in Civil War (2006–2007) was received negatively, with most readers seeing him as the villain.[219]

Iron Man became widely popular following the success of the 2008 film Iron Man, which made him one of Marvel's most recognizable characters,[1] and the film is credited with redefining the superhero film genre.[220][221] Since then, many publishers have listed Iron Man among the top ten in lists of best superheroes and best Marvel characters.[222][223] Iron Man's portrayal of futuristic technology has affected public image of how these technologies may develop. Heavy use of augmented reality interfaces by Iron Man, in his helmet's heads-up display and elsewhere, has informed public awareness of the technology.[224] In 2019, a statue representing the character in his Iron Man armor was erected in Forte dei Marmi, Italy, to memorialize the character's actions in Avengers: Endgame (2019) and as a reminder that "the future of humanity depends on our decisions ... that all of us must be heroes!".[225]

In other media

In 2008, a film adaptation titled Iron Man was released, starring Robert Downey Jr. as Tony Stark and directed by Jon Favreau. Iron Man was met with positive reviews from film critics,[226] grossing $318 million domestically and $585 million worldwide, and became the first in the long-running Marvel Cinematic Universe.[227] Downey's casting was praised, as was his portrayal of the character; Downey's own recovery from substance abuse was seen as creating a personal connection with the character.[228] Downey reprises his role in Iron Man 2 (2010), Marvel's The Avengers (2012), Iron Man 3 (2013), Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015), Captain America: Civil War (2016), Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017), Avengers: Infinity War (2018), and Avengers: Endgame (2019).[229] Iron Man supporting characters are set to appear in their own Marvel Cinematic Universe titles, Ironheart and Armor Wars.[230]

Iron Man's first animated appearance was in a segment of the 1966 series The Marvel Super Heroes, which adapted comic book drawings into animations, and has since been featured in the animated series Iron Man (1994–1996) and Iron Man: Armored Adventures (2009–2012). He also made many appearances in other Marvel animated programs, particularly those featuring the Avengers, and there have been multiple Iron Man direct-to-video releases.[231]

Iron Man has featured in several video games, including Iron Man (2008) and Iron Man 2 (2010), which were released as adaptations of his Marvel Cinematic Universe films. He also featured in the PlayStation VR game Iron Man VR (2020). An Iron Man action-adventure game was announced in 2022 to be developed by Motive Studio. He also appeared in many other Marvel video games, such as those featuring the Avengers.[232]

References

- ^ a b c Darowski 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Housel & Housel 2010, p. 245.

- ^ Cooley & Rogers 2015, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d Mills 2013, p. 123.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2008, p. 91.

- ^ a b Zanco 2015, p. 167.

- ^ Housel & Housel 2010, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Dunn 2010, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Howe 2012, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d Patton 2015, p. 7.

- ^ Mills 2013, p. 106.

- ^ a b c Patton 2015, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Howe 2012, p. 45.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 94.

- ^ a b Friedenthal 2021, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Howe 2012, p. 56.

- ^ Howe 2012, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d Patton 2015, p. 8.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 99.

- ^ Alaniz 2015, p. 52.

- ^ Wright 2001, pp. 222–223.

- ^ a b Henebry 2015, p. 110.

- ^ Henebry 2015, pp. 99–101.

- ^ Howe 2012, p. 89.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 130.

- ^ Henebry 2015, p. 101.

- ^ Henebry 2015, pp. 102–105.

- ^ Cassell 2011, p. 24.

- ^ a b Vohlidka 2015, p. 121.

- ^ Cassell 2011, p. 28.

- ^ Henebry 2015, p. 116.

- ^ Howe 2012, p. 188.

- ^ a b Henebry 2015, p. 111.

- ^ Henebry 2015, p. 112.

- ^ Sacks 2015, p. 138.

- ^ Sacks 2015, p. 139.

- ^ a b Ridout 1992, p. 6.

- ^ Howe 2012, p. 223.

- ^ a b c d Ridout 1992, p. 7.

- ^ Johnson 2007, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Sacks 2015, p. 140.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 187.

- ^ Johnson 2007, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Sacks 2015, pp. 140–142.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 189.

- ^ a b Johnson 2007, p. 44.

- ^ a b Van Hise, James (January 1987). "With Armor and Shield". Comics Feature. No. 51. Movieland Publishing. pp. 33–35.

- ^ a b Zanco 2015, pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b c d Chambliss 2015, p. 152.

- ^ Costello 2009, p. 145.

- ^ Donovan & Richardson 2010, pp. 189–190.

- ^ a b Darowski 2015b, pp. 171–173.

- ^ a b c Darowski 2015b, p. 175.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 269.

- ^ Darowski 2015b, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Mulligan 2015, p. 218.

- ^ a b Chambliss 2015, p. 148.

- ^ Howe 2012, p. 373.

- ^ a b c d e Zehr 2011, p. 181.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 280.

- ^ Howe 2012, p. 394.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 285.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 289.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 311.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2008, p. 325.

- ^ Darowski 2015a, p. 189.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, pp. 323–324.

- ^ a b Friedenthal 2021, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Friedenthal 2021, p. 83.

- ^ White 2010, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Darowski 2015a, p. 181.

- ^ Friedenthal 2021, p. 85.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 335.

- ^ Spanakos 2010, p. 129.

- ^ a b Schedeen, Jesse (October 24, 2012). "The Invincible Iron Man #527 Review". IGN. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Phillips, Dan (April 15, 2010). "Iron Man Legacy #1 Review". IGN. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Overpeck 2017, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Truitt, Brian (November 6, 2012). "Kieron Gillen explores the ultimate human of 'Iron Man'". USA Today. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse (November 12, 2014). "Superior Iron Man #1 Review". IGN. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse (October 6, 2015). "The Invincible Iron Man #1 Review". IGN. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse (March 16, 2016). "International Iron Man #1 Review". IGN. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Friedenthal 2021, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Friedenthal 2021, p. 90.

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse (October 19, 2016). "Infamous Iron Man #1 Review". IGN. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse (June 21, 2018). "Iron Man's New Comic Is Fun but Shallow (Tony Stark: Iron Man #1 Review)". IGN. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Polo, Susana (September 21, 2020). "Tony Stark deleted Twitter because his mentions were horrible". Polygon. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse (September 21, 2022). "Marvel's New Iron Man Series Gives Tony Stark the 'Born Again' Treatment". IGN. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Marston, George (July 18, 2024). ""Iron Man is going to war": Marvel's new Iron Man #1 features Tony Stark's bizarre new "fury-powered" armor and a major returning foe". GamesRadar+. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hoskin 2008, Iron Man.

- ^ Friedenthal 2021, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Darowski 2015b, p. 176.

- ^ Friedenthal 2021, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b Mulligan 2015, p. 209.

- ^ Henebry 2015, pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b Sacks 2015, p. 141.

- ^ Mulligan 2015, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Hogan 2009, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Friedenthal 2021, p. 86.

- ^ a b c Hoskin 2010, Iron Man Update.

- ^ a b c d Fentiman 2019, p. 195.

- ^ a b c O'Sullivan 2016, Iron Man Update.

- ^ a b Polo, Susana (September 27, 2023). "Iron Man has reached his final form: a hot lady's trophy husband". Polygon. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Sacks 2015, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Faller 2010, p. 257.

- ^ Zanco 2015, pp. 164–167.

- ^ a b c Cooley & Rogers 2015, p. 80.

- ^ a b Spanakos 2010, p. 133.

- ^ Spanakos 2010, pp. 129, 133–134.

- ^ Terjesen 2010, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Malloy 2010, p. 117.

- ^ Michálek 2015, p. 196.

- ^ Robichaud 2010, p. 53.

- ^ Faller 2010, pp. 261–262.

- ^ a b Kirk 2020, p. 50.

- ^ Hogan 2009, p. 205.

- ^ a b Nielson 2010, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Michálek 2015, p. 193.

- ^ Alaniz 2015, p. 58.

- ^ Michálek 2015, p. 201.

- ^ White 2010, p. 172.

- ^ Curtis 2010, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Genter 2007, p. 968.

- ^ Mulligan 2015, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Sacks 2015, p. 137.

- ^ Novy 2010a, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Patterson & Patterson 2010, pp. 218–220.

- ^ Cooley & Rogers 2015, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Donovan & Richardson 2010, p. 193.

- ^ Patterson & Patterson 2010, p. 217.

- ^ Curtis 2010, p. 242.

- ^ a b Wright 2001, p. 222.

- ^ a b Patton 2015, p. 15.

- ^ This 2015, p. 17.

- ^ a b Dunn 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Patton 2015, p. 10.

- ^ a b Wright 2001, pp. 241–243.

- ^ a b Cooley & Rogers 2015, p. 88.

- ^ Curtis 2010, p. 238.

- ^ Robichaud 2010, p. 54.

- ^ Dunn 2010, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Henebry 2015, p. 103.

- ^ Genter 2007, pp. 967–968.

- ^ Malloy 2010, p. 115.

- ^ Zanco 2015, p. 168.

- ^ a b Hogan 2009, p. 201.

- ^ Patton 2015, p. 14.

- ^ Curtis 2010, pp. 236–238, 240.

- ^ Curtis 2010, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Mulligan 2015, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Rieder 2010, pp. 42–45.

- ^ Michálek 2015, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Hogan 2009, p. 210.

- ^ Alaniz 2015, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Zanco 2015, p. 164.

- ^ Dunn 2010, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Rieder 2010, p. 39.

- ^ Zehr 2011, p. 154.

- ^ Faller 2010, pp. 258–260.

- ^ Vohlidka 2015, p. 132.

- ^ Ridout 1992, p. 5.

- ^ Dunn 2010, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Mulligan 2015, p. 205.

- ^ a b Zehr 2011, p. 6.

- ^ Ridout 1992, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Mulligan 2015, p. 208.

- ^ a b Hogan 2009, p. 203.

- ^ Zehr 2011, p. 78.

- ^ Zanco 2015, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Zehr 2011, p. 166.

- ^ Mulligan 2015, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Zehr 2011, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Dunn 2010, p. 18.

- ^ Mulligan 2015, p. 216.

- ^ a b Hoskin 2008, Pepper Hogan.

- ^ Michálek 2015, p. 197.

- ^ a b Michálek 2015, p. 198.

- ^ Hoskin 2010, Rescue.

- ^ Chambliss 2015, p. 150.

- ^ Chambliss 2015, p. 153.

- ^ a b c Chambliss 2015, p. 154.

- ^ Chambliss 2015, p. 158.

- ^ a b Hoskin 2008, Happy Hogan.

- ^ Patterson & Patterson 2010, p. 220.

- ^ Cassell 2012, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b Housel & Housel 2010, p. 246.

- ^ a b Kirk 2020, p. 51.

- ^ Novy 2010b, pp. 147–149.

- ^ Patterson & Patterson 2010, p. 228.

- ^ Minett & Schauer 2017, p. 58.

- ^ Henebry 2015, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Housel & Housel 2010, pp. 251–253.

- ^ Housel & Housel 2010, p. 252.

- ^ Kirk 2020, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Patton 2015, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Alaniz 2015, p. 59.

- ^ Wright 2001, p. 241.

- ^ Alaniz 2015, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Alaniz 2015, p. 65.

- ^ Howe 2012, pp. 56, 106.

- ^ Housel & Housel 2010, p. 250.

- ^ Iadonisi 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Henebry 2015, p. 98.

- ^ a b Iadonisi 2015, p. 46.

- ^ Iadonisi 2015, p. 41.

- ^ a b Darowski 2015b, p. 178.

- ^ Iadonisi 2015, p. 44.

- ^ Henebry 2015, pp. 111–113.

- ^ Vohlidka 2015, p. 119.

- ^ a b Zanco 2015, p. 166.

- ^ Johnson 2007, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Zanco 2015, p. 169.

- ^ O'Sullivan 2015, 'Ultimate Universe' (Reality-1610).

- ^ Hoskin 2010, Iron Man (2020 AD).

- ^ Dunn 2010, p. 23.

- ^ a b Schedeen, Jesse (May 2, 2013). "Top 25 Iron Man Stories". IGN. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Garza, Joe (June 28, 2022). "The 15 Best Iron Man Comics You Need To Read". SlashFilm. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Hunt, James (April 28, 2008). "Alternate Cover: the best and worst Iron Man stories". Den of Geek. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Lydon, Pierce (January 19, 2022). "Best Iron Man stories of all time". GamesRadar+. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Darowski 2015a, pp. 181–185.

- ^ Crump, Andy (May 2, 2018). "Why Iron Man was the most pivotal movie of the last decade". The Week. Archived from the original on September 5, 2023. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ Robinson, Joanna (November 29, 2017). "Marvel Looks Back at Iron Man—the Movie That Started It All". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on October 4, 2023. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ Macias, Gil; Hughes, William; Smart, Jack; Jackson, Matthew; Gajjar, Saloni; Carr, Mary Kate; Barsanti, Sam (July 8, 2022). "The 100 Best Marvel Characters Ranked: 20–1". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on August 3, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2022.

- ^ Cartelli, Lance (February 15, 2018). "The 50 Most Important Superheroes, Ranked". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2022.

- ^ Pedersen & Simcoe 2012.

- ^ Weiss, Josh (September 5, 2019). "Italy erects Iron Man statue to honor Tony Stark's noble death in Avengers: Endgame". Syfy. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2022.

- ^ Yamato, Jen (May 1, 2008). "Iron Man is the Best-Reviewed Movie of 2008!". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ^ "Iron Man". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ Sacks 2015, p. 145.

- ^ Miller, Ross (April 25, 2019). "Everything you need to remember about the OG Avengers before Endgame". Polygon. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Radulovic, Petrana; Polo, Susana; Welsh, Oli; Goslin, Austen (September 23, 2020). "Every Marvel movie and TV release set for 2024 and beyond". Polygon. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Goldman, Eric (April 29, 2013). "Iron Man's TV History". IGN. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ Good, Owen S. (September 20, 2022). "EA is Making an Iron Man Video Game". Polygon. Archived from the original on September 3, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

Bibliography

- Cassell, R. Dewey (2011). "An Artist for All Seasons: A Brief Look at the Life and Career of George Tuska". Alter Ego. No. 99. TwoMorrows Publishing. pp. 3–35.

- Cassell, Dewey (2012). "If Only Those Walls Could Talk... The Avengers Mansion". Back Issue!. No. 56. TwoMorrows Publishing. pp. 15–17.

- Costello, Matthew J. (2009). Secret Identity Crisis: Comic Books and the Unmasking of Cold War America. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-4411-0859-3.

- Darowski, Joseph J., ed. (2015). The Ages of Iron Man: Essays on the Armored Avenger in Changing Times. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-2074-9.

- Alaniz, José. "'Does Khrushchev Tell Kennedy?'". In Darowski (2015).

- Chambliss, Julian C. "War Machine". In Darowski (2015).

- Cooley, Will; Rogers, Mark C. "Ike's Nightmare". In Darowski (2015).

- Darowski, John (2015a). "'I would be the bad guy'". In Darowski (2015).

- Darowski, Joseph J. (2015b). "Cold Warrior at the End of the Cold War". In Darowski (2015).

- Henebry, Charles. "Socking It to Shell-Head". In Darowski (2015).

- Iadonisi, Richard A. "Fu Manchu Meets Maklu". In Darowski (2015).

- Michálek, Jason. "Feminizing the Iron". In Darowski (2015).

- Mulligan, Rikk. "Iron Icarus". In Darowski (2015).

- Patton, Brian. "'The Iron-Clad American'". In Darowski (2015).

- Sacks, Jason. "'Demon in a Bottle and Feet of Clay'". In Darowski (2015).

- This, Craig. "Tony Stark: Disabled Vietnam Veteran?". In Darowski (2015).

- Vohlidka, John M. "Countdown to #100". In Darowski (2015).

- Zanco, Jean-Philippe. "From Armor Wars to Iron Man 2.0". In Darowski (2015).

- Fentiman, David (2019). Marvel Encyclopedia (New ed.). DK. ISBN 978-1-4654-7890-0.

- Friedenthal, Andrew J. (2021). The World of Marvel Comics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-43111-7.

- Genter, Robert (2007). "'With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility:' Cold War Culture and the Birth of Marvel Comics". The Journal of Popular Culture. 40 (6). Wiley-Blackwell: 953–978. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5931.2007.00480.x. ISSN 0022-3840.

- Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2008). Marvel Chronicle: A Year By Year History. DK. ISBN 978-0-7566-4123-8.

- Hogan, Jon (2009). "The Comic Book as Symbolic Environment: The Case of Iron Man". ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 66 (2): 199–214. ISSN 0014-164X. JSTOR 42578930.

- Hoskin, Michael (2008). The All-New Iron Manual. Marvel Comics.

- Hoskin, Michael (2010). Iron Man Iron Manual Mark 3. Marvel Comics.

- Howe, Sean (2012). Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-221811-7.

- Johnson, Dan (2007). "Marvel's Metal Men: Iron Man's Bob Layton and David Michelinie". Back Issue!. No. 25. TwoMorrows Publishing. pp. 44–57.

- Kirk, John K. (2020). "The Many Loves of Bruce Wayne & Tony Stark". Back Issue!. No. 123. TwoMorrows Publishing. pp. 49–59.

- O'Sullivan, Mike, ed. (2015). Secret Wars: Official Guide to the Marvel Multiverse. Marvel Comics.

- O'Sullivan, Mike, ed. (2016). All-New, All-Different Marvel Universe. Marvel Comics.

- Mills, Anthony (2013). American Theology, Superhero Comics, and Cinema: The Marvel of Stan Lee and the Revolution of a Genre. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-01437-7.

- Pedersen, Isabel; Simcoe, Luke (2012). "The Iron Man Phenomenon, Participatory Culture, & Future Augmented Reality Technologies". CHI '12 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 291–300. doi:10.1145/2212776.2212807. ISBN 978-1-4503-1016-1. S2CID 14161327. Archived from the original on September 5, 2023. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- Ridout, Cefn (1992). "Introduction". The Many Armors of Iron Man. Marvel Comics. pp. 4–9. ISBN 0-87135-926-X.

- White, Mark D., ed. (2010). Iron Man and Philosophy: Facing the Stark Reality. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-48218-6.

- Curtis, David Valleau. "Iron Man and the Problem of Progress". In White (2010).

- Donovan, Sarah K.; Richardson, Nicholas P. "Does Tony Stark Use a Moral Compass?". In White (2010).

- Dunn, George A. "The Literal Making of a Superhero". In White (2010).

- Faller, Stephen. "Iron Man's Transcendant Challenge". In White (2010).

- Housel, Rebecca; Housel, Gary. "Engendering Justice in Iron Man". In White (2010).

- Malloy, Daniel P. "™ and © Stark Industries: Iron Man and Property Rights". In White (2010).

- Nielson, Carston Fogh. "Flawed Heroes and Courageous Villains: Plato, Aristotle, and Iron Man on the Unity of the Virtues". In White (2010).

- Novy, Ron (2010a). "Fate at the Bottom of a Bottle: Alcohol and Tony Stark". In White (2010).

- Novy, Ron (2010b). "Iron Man in a Chinese Room: Does Living Armor Think?". In White (2010).

- Patterson, Stephanie; Patterson, Brett. "'I Have a Good Life': Iron Man and the Avenger School of Virtue". In White (2010).

- Rieder, Travis N. "The Technological Subversion of Technology". In White (2010).

- Robichaud, Christopher. "Can Iron Man Atone for Tony Stark's Wrongs". In White (2010).

- Spanakos, Tony. "Tony Stark, Philosopher King of the Future?". In White (2010).

- Terjesen, Andrew. "Tony Stark and 'The Gospel of Wealth'". In White (2010).

- Wright, Bradford W. (2001). Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6514-5.

- Yockey, Matt (2017). Make Ours Marvel: Media Convergence and a Comics Universe. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-4773-1250-6.

- Minett, Mark; Schauer, Bradley. "Reforming the 'Justice' System". In Yockey (2017).

- Overpeck, Deron. "Breaking Brand". In Yockey (2017).

- Zehr, E. Paul (2011). Inventing Iron Man: The Possibility of a Human Machine. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0488-2.

External links

- Iron Man at Marvel.com

- Iron Man (Tony Stark) at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Tony Stark on Marvel Database, a Marvel Comics wiki

- Iron Man

- Avengers (comics) characters

- Characters created by Don Heck

- Characters created by Jack Kirby

- Characters created by Larry Lieber

- Characters created by Stan Lee

- Cold War in popular culture

- Comics characters introduced in 1963

- Cyborg superheroes

- Fictional alcohol abusers

- Fictional aerospace engineers

- Fictional arms dealers

- Fictional billionaires

- Fictional business executives

- Fictional characters from New York City

- Fictional electronic engineers

- Fictional inventors in comics

- Fictional military strategists

- Fictional engineers

- Fictional roboticists

- Fictional socialites

- Fictional technopaths

- Iron Man characters

- Marvel Comics adapted into films

- Marvel Comics adapted into video games

- Marvel Comics American superheroes

- Marvel Comics businesspeople

- Marvel Comics cyborgs

- Marvel Comics film characters

- Marvel Comics male superheroes

- Marvel Comics scientists

- S.H.I.E.L.D. agents

- Superheroes who are adopted

- Fiction about telepresence

- Fictional hackers

- Fictional mechanics