TRIZ

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. (June 2024) |

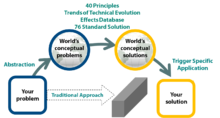

TRIZ (/ˈtriːz/; Russian: теория решения изобретательских задач, romanized: teoriya resheniya izobretatelskikh zadach, lit. 'theory of inventive problem solving') combines an organized, systematic method of problem-solving with analysis and forecasting techniques derived from the study of patterns of invention in global patent literature. The development and improvement of products and technologies in accordance with TRIZ are guided by the laws of technical systems evolution.[1][2] Its development, by Soviet inventor and science-fiction author Genrich Altshuller and his colleagues, began in 1946. In English, TRIZ is typically rendered as the theory of inventive problem solving.[3][4]

TRIZ developed from a foundation of research into hundreds of thousands of inventions in many fields to produce an approach which defines patterns in inventive solutions and the characteristics of the problems these inventions have overcome.[5] The research has produced three findings:

- Problems and solutions are repeated across industries and sciences.

- Patterns of technical evolution are replicated in industries and sciences.

- The innovations have scientific effects outside the field in which they were developed.

TRIZ applies these findings to create and improve products, services, and systems.[6]

History

[edit]TRIZ was developed by the Soviet inventor and science-fiction writer Genrich Altshuller and his associates. Altshuller began developing TRIZ in 1946 while working in the inventions-inspection department of the Caspian Sea flotilla of the Soviet Navy. His job was to help initiate invention proposals, to rectify and document them, and to prepare applications to the patent office. Altshuller realized that a problem requires an inventive solution if there are technical contradictions (improving one parameter negatively affects another).

His work on what later became TRIZ was interrupted in 1950 by his arrest and 25-year sentence to the Vorkuta Gulag. The arrest was partially triggered by letters he and Raphael Shapiro sent to Stalin, ministers, and newspapers about Soviet government decisions they considered erroneous.[7] Altshuller and Shapiro were freed during the Khrushchev Thaw which followed Stalin's death in 1953, [8] and they returned to Baku. The first paper on TRIZ, "On the psychology of inventive creation", was published in 1956 in the Issues in Psychology (Voprosi Psichologii) journal.[9]

Altshuller observed clever and creative people at work, discovering patterns in their thinking with which he developed thinking tools and techniques. The tools included Smart Little People[10] and Thinking in Time and Scale (or the Screens of Talented Thought).[11]

In 1986, Altshuller's attention shifted from technical TRIZ to the development of individual creativity. He developed a version of TRIZ for children which was tried in several schools.[12] After the Cold War, emigrants from the former Soviet Union brought TRIZ to other countries.[13]

Principles

[edit]

One tool which evolved as an extension of TRIZ was a contradiction matrix.[14] The ideal final result (IFR) is the ultimate solution of a problem when the desired result is achieved by itself.[15]

Altshuller screened patents to discover which contradictions were resolved or eliminated by the invention and how this had been achieved. He developed a set of 40 inventive principles and, later, a matrix of contradictions.[14] Although TRIZ was developed from analyzing technical systems, it has been used to understand and solve management problems. [16] The German-based nonprofit European TRIZ Association,[17] founded in 2000,[18] hosts conferences with publications.[19]

Use in industry

[edit]Samsung has invested in embedding TRIZ throughout the company.[20]

BAE Systems and GE also use TRIZ,[21][self-published source] Mars has documented how TRIZ led to a new patent for chocolate packaging.[22][self-published source] It has been used by Leafield Engineering, Smart Stabilizer Systems, and Buro Happold to solve problems and generate new patents.[23]

The automakers Rolls-Royce,[24] Ford, and Daimler-Chrysler, Johnson & Johnson, aeronautics companies Boeing, NASA, technology companies Hewlett-Packard, Motorola, General Electric, Xerox, IBM, LG, Samsung, Intel, Procter & Gamble, Expedia, and Kodak have used TRIZ methods in projects.[8][25][26][27]

TOP-TRIZ is a modern version of developed and integrated TRIZ methods. "TOP-TRIZ includes further development of problem formulation and problem modeling, development of Standard Solutions into Standard Techniques, further development of ARIZ and Technology Forecasting. TOP-TRIZ has integrated its methods into a universal and user-friendly system for innovation."[28] In 1992, several TRIZ practitioners fleeing the collapsing Soviet Union relocated and formed Ideation International.[29] They developed I-TRIZ, their version of TRIZ.

See also

[edit]- Brainstorming

- Dimension Time Cost model

- C-K theory

- Lateral thinking

- Morphological analysis

- Nine windows

- Systems theory

- Trial and error

- Systematic Inventive Thinking

References

[edit]- ^ Royzen, Zinovy (1993). “Application TRIZ in Value Management and Quality Improvement”. SAVE PROCEEDINGS Vol. XXVIII, 94-101. https://trizconsulting.com/TRIZApplicationinValueManagement.pdf.

- ^ Hua, Z.; Yang, J.; Coulibaly, S.; Zhang, B. (2006). "Integration TRIZ with problem-solving tools: a literature review from 1995 to 2006". International Journal of Business Innovation and Research. 1 (1–2): 111–128. doi:10.1504/IJBIR.2006.011091. Retrieved 2 October 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Barry, Katie; Domb, Ellen; Slocum, Michael S. "Triz - What is Triz". triz-journal.com. Real Innovation Network. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Sheng, I. L. S.; Kok-Soo, T. (2010). "Eco-Efficient Product Design Using theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ) Principles". American Journal of Applied Sciences. 7 (6): 852–858. doi:10.3844/ajassp.2010.852.858.

- ^ Vidal, Rosario; Salmeron, Jose L.; Mena, Angel; Chulvi, Vicente (2015). "Fuzzy Cognitive Map-based selection of TRIZ (Theory of Inventive Problem Solving) trends for eco-innovation of ceramic industry products". Journal of Cleaner Production. 107: 202–214. Bibcode:2015JCPro.107..202V. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.04.131. hdl:10234/159616.

- ^ "What is TRIZ?". Archived from the original on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ "Генрих Саулович Альтшуллер (Genrich Saulovich Altshuller - short biography)". www.altshuller.ru. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010.

- ^ a b Wallace, Mark (29 June 2000). "The science of invention". Salon.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ Altshuller, G. S.; Shapiro, R. B. (1956). "О Психологии изобретательского творчества (On the psychology of inventive creation)". Вопросы Психологии (The Psychological Issues) (in Russian) (6): 37–39. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ [reference to p 110] Altshuller, G.S. (1984) Creativity as an Exact Science: the Theory of the Solution of Inventive Problems Archived 2015-05-30 at the Wayback Machine Translated by Williams, A. Gordon and Breach Science Publishers Inc]

- ^ [reference to p 121] Altshuller, G.S. (1984) Creativity as an Exact Science: the Theory of the Solution of Inventive Problems Translated by Williams, A. Gordon, and Breach Science Publishers Inc]

- ^ "A brief history of TRIZ" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Webb, Alan (August 2002). "TRIZ: an inventive approach to invention". Manufacturing Engineer. 12 (3): 117–124. doi:10.1049/em:20020302.

- ^ a b "Contradictions Matrix - TRIZ Tools Oxford Creativity". www.triz.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015.

- ^ "Rezultat Idealny - TRIZ - Baza Wiedzy, Szkolenia, Warsztaty, Wdrożenia Feed".

- ^ "'The overall benefits are potentially enormous': Bucks County Council granted ABS license with emergency services group". 8 August 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ "ETRIA portal". www.etria.eu. Archived from the original on 1 November 2017.

- ^ "ETRIA – European TRIZ Association". triz-journal.com. 21 January 2001. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "European TRIZ Association". WorldCat. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Shaughnessy, Haydn. "What Makes Samsung Such An Innovative Company?". Forbes. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018.

In 2003 TRIZ led to 50 new patents for Samsung and in 2004 one project alone, a DVD pick-up innovation, saved Samsung over $100 million. TRIZ is now an obligatory skill set if you want to advance within Samsung.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Mars Chocolate Packaging Case Study". www.triz.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018.

- ^ "Manufacturing". www.imeche.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015.

- ^ Gadd, Karen (2011). TRIZ for Engineers. United Kingdom: Wileys. p. 38. ISBN 978-0470741887.

- ^ Jana, Reena (31 May 2006). "The World According to TRIZ". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 22 June 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ Hamm, Steve (25 December 2008). "Tech Innovations for Tough Times". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ Lewis, Peter (19 September 2005). "A Perpetual Crisis Machine". CNNMoney.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ Royzen, Zinovy (2014), "TOP-TRIZ, Method for Innovation, Applications, Implementation." 5th International Conference on Systematic Innovation, San Jose, CA, July 16–18, 2014, Proceeding, ISBN 978-986-90782-1-4, pp. 253-282. https://www.i-sim.org/icsi/FullProceedings/ICSI2014-FullProceedings.pdf.

- ^ "Who We Are". Ideation International. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Altshuller, Genrich (1999). The Innovation Algorithm: TRIZ, systematic innovation, and technical creativity. Worcester, MA: Technical Innovation Center. ISBN 978-0-9640740-4-0.

- Altshuller, Genrich (1984). Creativity as an Exact Science. New York, NY: Gordon & Breach. ISBN 978-0-677-21230-2.

- Altshuller, Genrich (1994). And Suddenly the Inventor Appeared. translated by Lev Shulyak. Worcester, MA: Technical Innovation Center. ISBN 978-0-9640740-2-6.

- Altshuller, Genrich (2005). 40 Principles:Extended Edition. translated by Lev Shulyak with additions by Dana Clarke, Sr. Worcester, MA: Technical Innovation Center. ISBN 978-0-9640740-5-7.

- Gadd, Karen (2011). TRIZ for Engineers: Enabling Inventive Problem Solving. UK: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-4707418-8-7.

- Haines-Gadd, Lilly (2016). TRIZ for Dummies. UK: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-1191074-7-7.

- Royzen, Zinovy (2009), Designing and Manufacturing Better Products Faster Using TRIZ, TRIZ Consulting, Inc.

- Royzen, Zinovy (2020). Systematic engineering innovation. Seattle, WA. ISBN 978-0-9728543-4-4. OCLC 1297849736.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Karasik, Yevgeny B. (2021). Duality revolution : discovery of new types and mechanisms of duality that are revolutionizing science and technology as well as our ability to solve problems. [place of publication not identified]. ISBN 979-8-5044-3426-1. OCLC 1363847265.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)